![]()

Shema

By Rabbi Dr. Hillel ben David (Greg Killian)

![]()

Twenty-five - The Mystery of Unity

![]()

Introduction

In this study I would like to look at some interesting aspects of the the Shema, the quintessential statement of the Jew. Its importance is underscored by its inclusion in the tefillin, mezuzah, and our prayers.

For those who do not know what the Shema is, it is worth while to give a basic definition that we can expand upon throughout this study. The word ‘Shema’ is a an English translitteration of the Hebrew word שמע. Shema means ‘to hear’, and is taken from the first word of the following Torah command:

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 6:4-9 Hear, O Israel: HaShem our G-d, HaShem is one: 5 And thou shalt love HaShem thy G-d with all thine heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy might. 6 And these words, which I command thee this day, shall be in thine heart: 7 And thou shalt teach them diligently unto thy children, and shalt talk of them when thou sittest in thine house, and when thou walkest by the way, and when thou liest down, and when thou risest up. 8 And thou shalt bind them for a sign upon thine hand, and they shall be as frontlets between thine eyes. 9 And thou shalt write them upon the posts of thy house, and on thy gates.

The Shema is an affirmation of our covenantal relationship and a declaration of faith in one G-d. The obligation to recite the Shema is the beginning of the obligation to pray, yet separate from it. This means that we must also pray in addition to saying the Shema. Saying the Shema is the beginning of Torah study since the two commands are so closely related. A Jew is obligated to say Shema in the morning and at night, as we can see from the above passage.

The Master of Nazareth, Yeshua, called the Shema, “the first commandment of all”.

Mordechai (Mark) 12:28-34 And one of the scribes came, and having heard them reasoning together, and perceiving that he had answered them well, asked him, Which is the first commandment of all? 29 And Yeshua answered him, The first of all the commandments is, Hear, O Israel; The HaShem our God is one HaShem: 30 And thou shalt love the HaShem thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy strength: this is the first commandment. 31 And the second is like, namely this, Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. There is none other commandment greater than these. 32 And the scribe said unto him, Well, Master, thou hast said the truth: for there is one God; and there is none other but he: 33 And to love him with all the heart, and with all the understanding, and with all the soul, and with all the strength, and to love his neighbor as himself, is more than all whole burnt offerings and sacrifices. 34 And when Yeshua saw that he answered discreetly, he said unto him, Thou art not far from the kingdom of God. And no man after that durst ask him any question.

The Rambam, as we shall see, cited ‘belief in G-d’ as the first commandment. The Master of Nazareth taught that that the Shema was the first commandment of all. Of course, this means that the Shema is the quinessential means of expressing our belief that HaShem is one and that there exists nothing except HaShem.

The Shema consists of three paragraphs extracted from several Torah verses. Before we look at the details, it is worthwhile to understand the importance of this prayer / command.

The importance of this prayer is underscored by the Talmud,[1] where we learn that the reading of the Shema morning and evening fulfills an important mitzva:

Yehoshua (Joshua) 1:8 This book of the law shall not depart out of thy mouth; but thou shalt meditate therein day and night, that thou mayest observe to do according to all that is written therein: for then thou shalt make thy way prosperous, and then thou shalt have good success.

So important is this prayer that as soon as a child begins to speak his father is directed[2] to teach him the Shema and the verse:

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 33:4 Moses commanded us a law, even the inheritance of the congregation of Jacob.

The Talmud teaches us that this important prayer even reaches into our dreams:

Berachot 57a If a man were to dream that he is reciting the Shema, he is worthy that the Divine Presence should rest upon him…

The significance of the Shema is that it is a prayer, in which we accept the yoke of The Kingdom. The reciting of the first verse of the Shema is called the acceptance of the yoke of the kingship of G-d.[3] Accepting the yoke of the Kingdom[4] is a vital part of understanding the Shema.

The Ramban[5] has said that the primary function of all the mitzvot is to learn the fear of G-d.[6] Chazal[7] teach that “Fear of G-d”[8] is reverential awe. This suggests that the Shema is the most important expression of our Fear of God.

There are four rungs in the ladder of prayer. In the first phase of the “service of the heart“[9] (which culminates in the first section of the Shema), the objective is to develop a feeling of love towards HaShem, a yearning and craving to draw close to Him. The second phase (coinciding with the second section of the Shema) is the development of feelings of reverence and awe toward HaShem. The third phase (associated with the blessing “True and Enduring”, recited between the Shema and the Amida) is the fusion of love and awe in our relationship with HaShem. In the fourth phase (attained during the silent recitation of the Amida) we transcend emotion itself, abnegating all feeling and desire to achieve an utter commitment and unequivocal devotion to HaShem.

The directives of the Shema, Devarim 6:4ff, intimate two ways for Israel to express its love for HaShem: to do and to hear. Later Hakhamim will refer to these “ways” as “duties of the limbs” and “duties of the heart“, the “duties of the limbs” implying what the Hakhamim came to call halakha. Derived from the causative verb halak (to walk, i.e., to make someone else walk, to lead, to guide), halaka is that component of Torah which provides guidance through definitive rulings or commandments (mitzvot[10]). It answers the questions ‘what,’ ‘when,’ and ‘how’ in Israel’s call to holiness.

Rambam[11] lists the reading of the Shema as the tenth of the positive mitzvot:

|

Mitzva # |

Verse # |

248 Positive Mitzvot |

|

P 1 |

Ex. 20:22 |

Believing in G-d |

|

P 2 |

Deut. 6:4 |

Unity of G-d |

|

P 3 |

Deut. 6:5 |

Loving G-d |

|

P 4 |

Deut. 6:13 |

Fearing G-d |

|

P 5 |

Exo23:25; Deu11:13; 13:5 |

To serve G-d |

|

P 6 |

Deut 10:20 |

To cleave to G-d |

|

P 7 |

Deut. 10:20 |

Taking an oath by G-d’s Name |

|

P 8 |

Deut. 28:9 |

Walking in G-d’s ways |

|

P 9 |

Lev. 22:23 |

Sanctifying G-d’s Name |

|

P 10 |

Deut. 6:7 |

Reading the Shema twice daily |

Let’s look at the details of the “Shema”, the prayer HaShem‘s people pray twice a day; once in the evening and once in the morning. The basic command is found in Devarim (Deuteronomy) 6:4-9, as we saw earlier.

In the above passage, you will notice that we speak of these commands when we sit at home. When do we sit at home? We sit at home in the evening. Then we talk of them when we walk along the road. When do we walk along the road? We walk along the road in the morning. The scripture then goes on to tell us to talk of them when we lie down. When do we lie down? We lie down in the evening. Finally, we are to talk about them when we get up. When do we get up? We get up in the morning. So, the pattern holds: “evening” begins the day, and “morning” ends the day.

HaShem is One!

The human body has a mashal, an analogy, about HaShem‘s oneness. This mashal is based on our observation of the world. Our observation is that this world is composed of differentiated parts. We observe this same differentiation when we observe other human beings. They seem to be composed of parts: Head, hands, legs, etc. This is analogous to this world which seems to be composed of parts. Further, as we saw in our last mashal, HaShem seems to be composed of parts. Yet, we know that HaShem is ONE. That is our declaration in the Shema: HaShem is one! To understand this paradox, HaShem gives us a mashal in our own bodies that will help us understand this paradox.

When others observe us, they see parts. When we observe ourselves externally we see parts. However, when we grasp ourselves internally we see only the totality. We do not grasp ourselves, internally, as a collection of parts. We see only… ourselves! When we use our intellect, or our creativity, we do not have the sensation of moving to another part. We have only the sensation of ourselves as a unity. Our awareness of ourselves is always in totality. We grasp ourselves as a unity, not a collection of parts.

From this mashal we learn how to view HaShem as one. Since the whole world is nothing more than a manifestation of HaShem, we learn that despite the appearance of parts, this world is one as HaShem is one. Thus we can begin to understand a bit about the unity of HaShem by observing how we are unified to ourselves.

Malchut

- Kingship

One of the important functions of the Shema is to make HaShem our King. The Rambam taught this concept:[12]

“The Second Mitzva is the commandment in which we are commanded regarding knowledge of the Oneness [of G-d], namely, that we should know that the Creator of Existence and its Primary Cause is One, as He stated, “Understand, O Israel, HaShem is our G-d, HaShem is One“ (Devarim 6:4). In many midrashim you will find the Sages saying, “Al menas le’yached es Shemi” (“for the purpose of unifying My Name“) and “Al menas le’yachdeini” (literally, “for the purpose of unifying Me” - obviously, we cannot take this literally), and the like. Their intent in this statement is that the only reason He took us out of slavery and acted kindly and benevolently with us was in order that we should be a state of knowledge of [His] Oneness, for we are obligated in this. In many places this mitzva is referred to as “the mitzva of Oneness.” This mitzva is also called “Malchut,” as the Sages say, “To accept upon oneself the yoke of the Malchut Shamayim”,[13] which means recognition and knowledge of [His] Oneness”.

Thus, we see that according to Chazal, the idea of “Malchut HaShem“ (Kingship of HaShem) is the same as the idea of “Yichud HaShem“, the seclusion of HaShem.[14] With this idea, the Adon Olam prayer makes sense. To say that HaShem was Melech (King) before any form was created is to say that He was One before He created the universe. Likewise, to say that HaShem will be Melech (King) after everything ceases to exist is to say that His Oneness will not be affected in any way when the universe ends. Lastly, we can understand the tenth pasuk of malchiyot (Kingship). Even though the Shema doesn’t mention any form of the word “Melech” (King) it is nevertheless the perfect expression of Malchut HaShem (Kingship of HaShem), for it explicitly states that HaShem is One.

There is one more question we must answer: How is Malchut (Kingship) a metaphor for Oneness? The Rambam may have supported his statement from the words of Chazal, but what were Chazal thinking when they decided to refer to the idea of Yichud HaShem (the seclusion of HaShem) by the analogy of Malchut?

Before we answer this question, let us briefly review the idea of HaShem‘s Existence and HaShem‘s Oneness. The Rambam writes:[15]

“The First Fundamental Principle is the Existence of the Creator, praised is He. Namely, that there Exists an Existence which is perfect in all manners of existence, and this Existence is the cause of the existence of all other existences, and through Him their existence is established, and their existence stems from Him. And if one could entertain the thought of the removal of His Existence, the existence of every other existence would be nullified and they would not remain in existence. And if one could entertain the thought of the removal of all existence besides Him, then His Existence, may He be exalted, would not be nullified, and would not lack, for He, may He be exalted, does not need the existence of any other . . . all of them are dependent on His Existence. And this first fundamental principle is that which is indicated by the statement, “I am HaShem your G-d.”

HaShem refers to Himself as “Eheyeh Asher Eheyeh”, the Existing Being Who Is the Existing Being, or the Inherently Existent Being. In other words, our existence is a contingent and accidental existence; at one point in time, we did not exist, and sooner or later, we shall cease to exist; we do not have to exist, but rather, we exist because HaShem wills it. HaShem‘s existence, on the other hand, is independent and essential; He always existed, exists now, and will always exist; unlike us, HaShem must exist. To suggest that HaShem could cease to exist is as absurd as the notion that water could cease to be wet. It is the nature of water to be wet, and it is the Nature of HaShem to Exist, as it were.

“The Second Fundamental Principle is His Oneness, may He be exalted. Namely, that this Cause of everything is One, not like the oneness of a species and not like the oneness of a class, and not like one unified composite, which can be divided into many unities, and not one like a simple body, which is one in number but is subject to division and subdivision ad infinitum, but He, may He be exalted, is One – a Oneness unlike any other oneness in any way.”

HaShem is One, and Only One. If our conception of G-d’s oneness contains any plurality whatsoever, then it must be incorrect. If our conception of G-d’s oneness is comparable in any way whatsoever to the oneness of anything else, it must be incorrect. G-d’s oneness is absolute, unshared by and incomparable to any other oneness. Oneness means that there is nothing else except HaShem!

Thus, Malchut HaShem is not a metaphor for HaShem‘s rulership over His creations. Rather, it is a metaphor for His Absolute Uniqueness - Oneness which is unlike any other. To say that HaShem is Melech (King) is to say that HaShem‘s existence and oneness are completely superior and utterly different than the existence and oneness of any of His subjects.

Rebbi formulated the idea in an eloquent, easy-to-remember expression: Malchut does not refer to HaShem‘s KingSHIP, but HaShem‘s KingNESS. It is not a metaphor for His rulership over His creations, for HaShem was King before the universe existed. Rather, Malchut is a metaphor for His uniqueness, distinctness, and utter superiority of existence to all other beings.

Time

Pirqe Abot II:13-14 MISHNAH 13. Rabbi Shimon said: “Be meticulous in reading the Shema and in prayer. When you pray, do not make your prayer a routine, but rather [entreaty for] mercy and supplication before G-d, as it is stated[16]: ‘For He is gracious and compassionate, slow to anger and abounding in loving kindness, and relenting of the evil decree.’ And do not consider yourself wicked in your self-estimation.”

QUESTION: Why did he single out these two mitzvot?

ANSWER: The Shema and the Amida prayer (Shemone Esre) are to be recited each morning, and there are specific times by which it should be done to properly fulfill the mitzva. Shema can be recited up to the end of the third hour of the day, and tefillah should be before the end of the fourth hour. These hours are not sixty minute hours, but sha’ot zemaniot, seasonal hours, i.e. the units obtained by dividing the day into twelve equal segments.

There is a question as to what is considered day with regard to determining the twelve hours. According to the Magen Avraham (58:1) the day is counted from Amud HaShachar, first light of dawn, until Tzet HaKochavim, nightfall. The Vilna Gaon maintains that the day for this calculation is from Netz HaChamah, sunrise, to Shekiat HaChamah, sunset. Thus, according to the Magen Avraham, the allotted period of time concludes earlier than according to the Vilna Gaon, and according to all calculations, the first three hours on a winter day is a shorter period of time than on a long summer day.

In the summer it is difficult to rise out of bed early because the nights are shorter, and in the winter because of the cold weather. Thus, the Mishna warns, “Be careful in reciting the Shema and Shemone Esre, that is, make a special effort to overcome your laziness throughout the year and recite them before the time lapses.”

Alternatively, the Talmud[17] says that the vatikin - the devoted ones, people of unusual humility and who held mitzvot in great esteem,[18] would take care to complete the recitation of the Shema with sunrise and immediately thereafter say the Shemone Esre. They would hasten to say the Shema immediately before sunrise (though it may be recited earlier) and the Shemoneh Esre immediately after sunrise so that they could recite the Shemoneh Esre at the earliest possible time and thereby link the redemption blessing [Ga’al Yisrael, which follows after the Shema] to the prayer. The Talmud praises this custom and says concerning anyone who does it that no harm will befall him all day.

Since this comes out very early in the day, especially during the summer, the Mishna encourages one to be diligent in the performance of Shema and tefillah, joining the two together as the vatikin did.

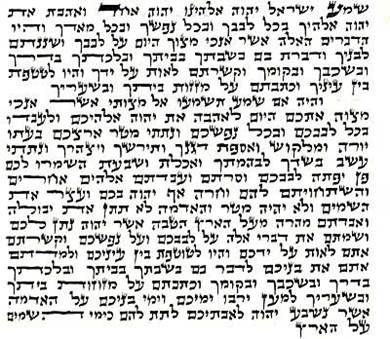

Letters

The Encyclopedia Judaica tells us that there are seventeen places in the Torah where a letter is written extra-large or extra-small: the scribal terminology is majuscule and miniscule. There are six miniscules and eleven majuscules. For example, the first letter in the Torah, the bet in the word Bereshit, is a majuscule (this is probably the origin of the illuminated capital of medieval manuscripts). The most famous majuscules are certainly the ones from the Shema in Devarim (Deuteronomy) 6:4. In this case, the letters are large to avoid confusion: a large ayin in the word shema to avoid confusion with aleph: ‘perhaps O Israel’. The large dalet to avoid confusion with resh: ‘the HaShem is another’. The following script illustrates these majuscules:

In the Shema prayer which says “Hear Israel HaShem our G-d is one“ the letters “ayin - ע” and “daled - ד” are written in large fonts. This is not only in the siddur it is also written this way in the Torah. The reason is because those two letters spell the word “aid - עד” which means witness in Hebrew. When is a witness needed? It is only when something is not revealed. And in the case of HaShem we as Jewish people have to be witnesses to his existence, hence the large “Ayin” and Daled”. That is a Jewish person’s role in this world. We have to reveal HaShem in a world that hides him. Being the only nation who was “witness” to a mass revelation of HaShem the Jewish people are by definition witnesses who need to reveal the hidden name of HaShem in this world.

Gematria

Shema

410 = ע = 70 + מ = 40 + ש = 300

410 = נ = 50 + כ = 20 + ש = 300 + מ = 40

Kadosh

410 = ש = 300 + ו = 6 + ד = 4 + ק = 100

In

The Synagogue

So, what does it mean to call upon the name of HaShem? To call upon the name of HaShem = to proclaim His Name = To confess His Name = to hold a Jewish Prayer service on Shabbat and weekdays which includes the reading of the Torah and a sermon. So attending Synagogue for a Jewish service is, in itself, making confession with the mouth since there in the presence of the community we recite the Shema. Which means that we publicly take upon ourselves the yoke of the Kingdom of Heaven.[19]

Midrash Psalm 19:7 Or, when Moses heard the reading of the Shema precede the Eighteen Benedictions, he knew that it was day; and when the Eighteen Benedictions preceded the reading of the Shema, he knew that it was night.

The synagogue service is set up in such a way that those who are saying the Shema on weekdays are also wearing their tzitzith and tefillin. On Shabbat we do not wear tefillin, but we do wear our tzitzith. Thus we speak about the tefillin and the tzitzith in the Shema while we have them immediately in front of us.

Torah Reading

In the annual Torah cycle, we read the parasha which contains the Shema on the Shabbat following Tisha B’Av.

In the triennial cycle of Torah readings we read the portion on the Shema (Deut. 6:4 – 7:11) along with the Ashlamata[20] of Zechariah 14:9-11, 16-21. We read Tehillim (Psalms) 116 and 117. In the Nazarean Codicil we read Matityahu 26:31-35 or Mark 14:26-31.

In the triennial cycle, we read this parasha, in the Tishri cycle, on the Shabbat after Succoth. In the Nisan cycle we read this parasha just after Pesach. As expected the two readings are six months apart, three and a half years later.

Question: Why should one wait to say kiddish levana[21] [on Motzei Tisha B’Av ] until after eating?

Answer: This is brought down in the Shulchan Aruch as Halacha. The main reson for this law, is that Kiddush Levana needs to be recited with Simcha.[22] One who is on an empty stomach for 25 hours and still in the Tisha B’Av mode cannot be doing it with Simcha, until after he has eaten and gets into the post Tisha B’Av mode of Geulah.[23]

Now we can understand why we read the portion of the Shema, in the triennial cycle, after the redemption of Pesach and after the redemption of Succoth.

Numbers in the Shema

Thirteen

The number thirteen is among the holiest of the numbers because it is closely associated with HaShem.

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 6:4 Hear, O Israel: HaShem our G-d, HaShem is one:

This pasuk, from the Shema, tells us a very important relationship:

The Shema is recited twice a day, by observant Jews, to obey the Torah command as found in the Shema itself. The goal of the Shema is not just to declare that HaShem is one, but rather to declare that HaShem is one and there is nothing in existence besides Him. The world and everything around us, is just an extension of HaShem.

To help us understand the making of many into one, HaShem gave us the sense of hearing. As an aside, HaShem gave us the human body, with all of its responses, in order to give us intimate insights into HaShem and His creation. If we understand what it means to hear, we can understand what it means to declare HaShem‘s oneness.

Hearing is a sense which requires us to assemble the sounds from another person, into a cohesive picture. Thus we would say that hearing is the forming of disparate parts into a single idea or picture. Literally we make many (sounds) into one (idea).

The Shema, which is uttered twice a day by every observant Jew, is an interesting perspective into hearing. Shema is normally translated as “hear”. Our Sages teach us that shema literally means the gathering of many and making them into one. The appropriateness of this definition is brought into sharp distinction when we see that the goal of the shema is that HaShem should be one and His name One.

To help us understand the relationship between HaShem and His oneness, HaShem gave us the Hebrew language. Part of this language is the fact that each letter not only has intrinsic meaning, but each letter also has a numeric value, as we learned in our study of the Hebrew letters. In the following chart, we can see that the numerical value of the Hebrew letters that form echad, whose meaning is one, is thirteen.

|

The gematria of echad - אחד is thirteen: |

א = 1 ח = 8 ד = 4 ---------- Total: 13 |

Not only does echad = 13, but the Hebrew word ahava (love) also has a numerical value of thirteen, as expressed verbally in the Nazarean Codicil:

1 Yochanan (John) 4:8 He that loveth not knoweth not HaShem; for HaShem is love.

Chazal teach that if two words have the same numeric value, then the essential meaning of the two words is the same. The above pasuk from the Nazarean Codicil[24] gives us another very important relationship:

HaShem is Ahavah (Love)

|

The gematria of ahavah - אהבה is thirteen: |

א = 1 ה = 5 ב = 2 ה = 5 ---------- Total: 13 |

Thus we learn that:

Echad (one) is ahavah (love)

HaShem is ahavah (love)

It follows, therefore, that we become one with HaShem, when we love Him and we love what He has created. Love means unification with the object of our love, and unification with HaShem means a unified heart in belief and devotion.

Thus we see that HaShem equals thirteen. Therefore the meaning of thirteen is the oneness and love of HaShem.

The yod-י hay-ה vav-ו hay-ה (HaShem) name has a gematria of 2 X 13 = 26, thirteen twice.

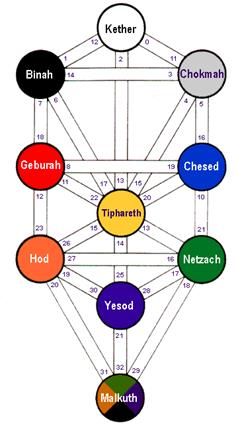

the word echad is spelled: אחד aleph-chet-dalet. In Kabbalah, the letter aleph (א) corresponds to the highest sefirah, Keter. The chet (ח) [with a numerical value of eight], in this case, represents the eight sefirot below Keter (Chachmah, Binah, Chesed, Gevurah, Tifferet, Netzach, Hod, and Yesod), until the last sefirah, Malchut. The letter dalet (ד), in Kabbalah, always represents Malchut. The following chart illustrates the sefirot, which represents creation:

Hence, the message of the Shema is: From the very top of creation until the very bottom of creation, even in the darkest, most physical parts of existence, you must know and be real with HaShem‘s Oneness. There is never a place that HaShem isn’t, just places where it is not proper to think about Him. There is never a time when HaShem isn’t, just times when He doesn’t seem apparent to us.

So, thirteen is another way of expressing the unity of HaShem.

Throughout the siddur (prayer book), and Jewish thought, thirteen is used to express HaShem and His oneness. This is made emphatic by the thirteen priciples which express the essentials of Jewish belief, which allow us to have an attachment to HaShem and His eternal world. The following list contains Rambam’s thirteen principles of faith, which we understand are the minimum requirements of Jewish belief:

1. HaShem exists.

3. HaShem is incorporeal.

4. HaShem is eternal.

5. Prayer is to be directed to HaShem alone and to no other.

6. The words of the prophets are true.

7. Moses’ prophecies are true, and Moses was the greatest of the prophets.

8. The Written Torah (first five books of the Bible) and Oral Torah (teachings now contained in the Talmud and other writings) were given to Moses.

9. There will be no other Torah.

10. HaShem knows the thoughts and deeds of men.

11. HaShem will reward the good and punish the wicked.

12. The Mashiach will come.

13. The dead will be resurrected.

Eighteen

Eighteen is the number of times HaShem‘s name is mentioned in shema[25]. When we declare the unity of HaShem we are connecting to The Source of life.

Midrash B’Midbar Rabba to Numbers 2:1-34 AND THE HASHEM SPOKE UNTO MOSES AND UNTO AARON, SAYING (Num. II, 1). In eighteen passages you find Moses and Aaron placed on an equal footing (i.e. the divine communication was made to both alike); to this the Eighteen Benedictions correspond (the reason, was that Moses and Aaron were both instruments of Israel’s deliverance, which would not have been effected without their prayers, hence the daily Prayer was likewise divided into Eighteen Benedictions.). From the three Patriarchs you derive the fixed ritual of praying three times a day. Abraham instituted morning prayer, as it is said, And Abraham got up early in the morning to the place where he had stood, etc. (Gen. XIX, 27), and ‘standing‘ signifies prayer, as it is said, Then stood up Phinehas, and prayed [English Version: ‘wrought judgment’] (Ps. CVI, 30). Isaac instituted afternoon prayer, as it is said, And Isaac went out to meditate in the field at eventide (Gen. XXIV, 63), and ‘meditation’ signifies prayer; as it is said, A prayer of the afflicted, when he faints, and pours out his meditation (E.V.: complaint) before the HaShem (Ps. CII, I). Jacob instituted evening prayer, as it is said, And he lighted (wayyifga’) upon the place, etc. (Gen. 28:11), and pegi’ah signifies prayer, as it is said, Therefore pray not you for this people ... neither make intercession (tifga’ - all three are from the root paga’) to Me (Jer. 7:16). In eighteen passages Moses and Aaron are conjoined, thus giving a hint for the Eighteen Benedictions which correspond to the eighteen references to the Divine Name occurring in the shema’ and in [the Psalm commencing,] A Psalm of David: Ascribe unto the HaShem, O you sons of might (Ps. 29:1). The three Patriarchs, then, introduced the custom of praying three times a day, while from Moses and Aaron and from the above-mentioned references to the Divine Name we infer that eighteen benedictions [must be said].

Twenty-five

- The Mystery of Unity

Soncino Zohar, Shemoth, Section 2, Page 139b ‘There are thirteen things enumerated apart from the stones, which, taken altogether, make twenty- five in the supernal mystery of the union. Corresponding to these twenty-five, Moses chiselled twenty-five letters in writing the mystery of the Shema (the twenty-five Hebrew letters contained in the verse, “hear, O Israel, the HaShem our G-d, the HaShem is one“). Jacob wished to express the unity below and did so in the twenty-four letters of the response to the Shema: “Blessed be the Name of His glorious Kingdom for ever and ever.” He did not bring it up to twenty-five because the Tabernacle was not yet.

Jacob wanted to establish the “Mystery of Unity” below [on earth], and composed the twenty-four letters of, “Blessed be the name of His glorious kingdom forever”. He didn’t make it twenty-five letters since the Tabernacle had yet to be built. Once the Tabernacle was built, the first word was completed ... With regard to this it says, “G-d spoke to him from the Tent of Meeting, saying ...”,[26] which has twenty-five letters.

What does this mean?

The “Mystery of Unity” refers to the supernatural state of existence when all negative traits disappear, traits that lead to division among people, such as hatred, jealousy, anger, and so on. This will be the “state of union” in the Messianic time, when the human inclination to do evil will be removed permanently.

What is the significance of the number twenty-four? The number twenty-four written in Hebrew letters is “kaf-dalet” - כד. The number twenty-four in Hebrew spells out the word “kad” or pitcher.

כד = Twenty-four = kad = pitcher

The number 24 is associated with judgment and severity. In some way, unity is also associated with the number twenty-four.

Forty-Two

- Cities of Refuge

The prayers found in the siddur contain several profound uses of the number forty-two. Whether in the number of words or letters, forty-two is an integral building block used by the prayers to achieve results.

In the verse Shema Israel,[27] HaShem Elokeinu, HaShem echad there are six words, and in the paragraph of Ve’ahavta (You shall love) till uvisharecha (and upon your gates) there are a total of forty-two words.

The Shema is recited twice a day, by observant Jews, to obey the Torah command, as found in the Shema itself. The goal of the Shema is not just to declare that HaShem is one, but rather to declare that HaShem is one and there is nothing in existence besides Him. The world and everything around us, is just an extension of HaShem. We are an extension of the oneness of HaShem.

To help us understand the making of many into one, HaShem gave us the sense of hearing. As an aside, HaShem gave us the human body, with all of its responses, in order to give us intimate insights into HaShem and His creation. If we understand what it means to hear, we can understand what it means to declare HaShem‘s oneness.

Hearing is a sense which requires us to assemble the sounds from another person, into a cohesive picture. Thus we would say that hearing is the forming of disparate parts into a single idea or picture. Literally we make many (sounds) into one (idea).

The Shema, which is uttered twice a day by every observant Jew, is an interesting perspective into hearing. Shema is normally translated as “hear”. Our Sages teach us that shema literally means the gathering of many and making them into one. The appropriateness of this definition is brought into sharp distinction when we see that the goal of the shema is that HaShem should be one and His name One.

This “oneness” was our state in Gan Eden.[28] Thus we would say that we find forty-two words in the Ve’ahavta[29] in order to facilitate our return to the state that we enjoyed in Gan Eden.

The goal of the Shema is oneness, but the goal of the Ve’ahavta is to create a new reality where Klal Israel[30] are bonded together in love for HaShem.

The verse of “Shema Israel” (Hear O Israel) accentuates “accepting the yoke of heaven“, and the paragraph of “Ve’ahavta” (and you shall love) deals with absolute love of HaShem.

The six cities of refuge correspond to the six words “Shema Yisrael Adonai Elohenu Adonai Ehad,” “Hear O Israel, the HaShem is our G-d, the HaShem is One.” Add the names of the forty-two Levitical cities, and you have forty-eight words, corresponding to the total of forty-eight Hebrew words in the passage beginning with “Hear, O Israel...”[31] and ending with “...and upon thy gates”.[32]

The foregoing implies that the words of the declaration of faith beginning with “Hear O Israel”[33] constitutes those “cities of refuge“ where any Jews, no matter what his sin, can find shelter and protection. If he accepts the yoke of the Kingdom of Heaven and loves HaShem, he will be saved from the accusers who pursue him.[34]

Two hundred and forty-eight

Zohar Ruth 97b There are 248 limbs in the body, and each word of Shema serves to protect one of them.

However, when making a tally of all of the sections of Shema, one comes up with only 245 words. How do we make up for the three missing words?

The Shulchan Aruch[35] writes that there are 245 words in the Shema, and in order to make it up to 248, corresponding to the 248 limbs of a person, the Shliach Tzibbur[36] repeats three words, HaShem Elokeichem Emet.[37] The Remo adds that that if one is not saying Shema with a tzibbur, then one adds at the beginning three words, Kel Melech Ne’eman (G-d faithful king).[38]

Torah

Study

Without regular Torah learning it is impossible to fulfill the words of the Shema[39] that we should “love HaShem our G-d with all of our heart, with all of our soul, and with all of our possessions”.

In The Shema

We can get a feeling for how important Torah study is, by looking at the command of HaShem, in the Shema, which we are commanded to recite twice a day:

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 6:4-9 Hear, O Israel: HaShem our G-d, HaShem is one: 5 And thou shalt love HaShem thy G-d with all thine heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy might. 6 And these words, which I command thee this day, shall be in thine heart: 7 And thou shalt teach them diligently unto thy children, and shalt talk of them when thou sittest in thine house, and when thou walkest by the way, and when thou liest down, and when thou risest up. 8 And thou shalt bind them for a sign upon thine hand, and they shall be as frontlets between thine eyes. 9 And thou shalt write them upon the posts of thy house, and on thy gates.

There is no way, for parents, to teach Torah to our children except we learn Torah first.[40] There is no way to speak the words of Torah “when we sit in our house and when we walk by the way”, except we study Torah first.

Can the time for the obligation of Torah study be quantified? It cannot. The time of each person’s obligation of Torah study is different, and varies according to personal circumstances. Those with a strong desire and lots of time should use the time wisely. We have time because HaShem has given us what we need with undue effort and time. When one does not have a long commute, very little overtime, and non-physical labor, he can be sure that HaShem gave him these things in order that he should have more time to study Torah, teach Torah, and perform the mitzvot. We are not given free time to indulge in pleasures.

The principle, as set out by a number of authorities, is that one must study the Torah in the time that is ‘free’.[41] As Rav Elchanan Wasserman[42] writes, during the time that a person spends at work, there is no obligation to study Torah: The obligation of Torah study is incumbent during the time that a person is not at work.

Further, the Rambam codified[43] that we are obligated to study the Torah day and night, just as the Shema commands. One can discern that he has fulfilled his obligation by simply reciting the Shema. Never the less, those who have more time should devote this additional time to the study of Torah.

A mourner is normally forbidden from studying the Torah because the study of Torah is a pleasurable experience. The mourner, however, is required to mourn, which is a time of sadness. Therefore he should refrain from doing things which bring pleasure, including the study of the Torah. Now, if we are commanded to study Torah night and day, why is the mourner exempt? After all, a command of HaShem should not be take lightly.

The Ramban[44] answered simply: The mourner will say Shema during morning and evening prayers; this minimal recitation automatically fulfills the mitzva of learning Torah. Therefore, the mourner is not entirely exempt from the mitzva of Torah Study because he needs to recite the Shema anyway.

Thus we see that while the mourner must study, his obligation is minimal in order that his pleasure should be minimal.

From the mourner’s obligation, we should understand that Torah study was intended to be pleasurable. This does not mean that we do not have to labor and sweat over our study. On the contrary, the pleasure only comes after long arduous hours of toil in the Torah.

Our Sages[45] teach that the minimum amount of Torah that we should study, no matter what, are the words of the Shema, which we recite / study twice a day. Both men and women are obligated to study Torah.[46] We saw, earlier, that this minimum amount of study is incumbent even on the mourner.

Menachoth 99b GEMARA: It was taught: R. Jose says, Even if the old [Shewbread] was taken away in the morning and the new was set down in the evening there is no harm. How then am I to explain the verse, ‘Before me continually’? [It teaches that] the table should not remain overnight without bread.

R. Ammi said, From these words of R. Jose[47] we learn that even though a man learns but one chapter in the morning and one chapter in the evening he has thereby fulfilled the precept of ‘This book of the law shall not depart out of thy mouth‘.[48]

R. Johanan said in the name of R. Simeon b. Yohai, Even though a man but reads the Shema’[49] morning and evening he has thereby fulfilled the precept of ‘[This book of the law] shall not depart’. It is forbidden, however, to say this in the presence of ‘amme ha-arez.[50] But Raba said, It is a meritorious act to say it in the presence of amme ha-arez.[51]

Remember

The Exodus

Chazal[52] teach that we are to remember the Exodus every day. There are two Torah pasukim, which form the mitzva of zekhirat Yetziat Mitzrayim, the daily remembrance of the Exodus:

Shemot (Exodus) 13:3 And Moshe said unto the people: ‘Remember this day, in which ye came out from Egypt, out of the house of bondage; for by strength of hand HaShem brought you out from this place; there shall no leavened bread be eaten.

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 16:3 Thou shalt eat no leavened bread with it; seven days shalt thou eat unleavened bread therewith, the bread of affliction; for thou camest forth out of the land of Egypt in haste: that thou mayest remember the day when thou camest forth out of the land of Egypt all the days of thy life.

We observe this mitzva, twice daily, in the blessing of “Emet VeYatziv” of the shacharit (morning) prayer and in “Emet VeEmuna” of the arbit (evening) prayer, both following the recitation of the Shema.

In

The Mezuzah

Though mezuzah refers to

the actual parchment itself, mezuzah is

colloquially used to also describe the decorative case the scroll is stored in.

Unfortunately, many homes have ornate cases containing invalid scrolls, or no

scroll at all! The internal depth of the command has been

stripped away, leaving nothing more than a posh exterior. Indeed, a xeroxed mezuzah is not kosher, and serves no purpose whatsoever.

Though mezuzah refers to

the actual parchment itself, mezuzah is

colloquially used to also describe the decorative case the scroll is stored in.

Unfortunately, many homes have ornate cases containing invalid scrolls, or no

scroll at all! The internal depth of the command has been

stripped away, leaving nothing more than a posh exterior. Indeed, a xeroxed mezuzah is not kosher, and serves no purpose whatsoever.

The scroll contains two passages from the Torah: Devarim 6:4-9 and Devarim 11:13-21. The scroll contains the first two paragraphs of the shema prayer, declaring the oneness of HaShem, and commanding us “to write [these words] on the doorpost of your house and on your gates”. The second passage teaches that Jewish destiny, both individually and nationally, depends upon fulfilling HaShem‘s will.

Mashiach

In the shema, HaShem commands us to love Him with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your might. If you will search the Tanach,[53] diligently, you will find only one individual who ever loved HaShem with all his might. This amazing individual could have been Mashiach except the people were not yet ready. King Yoshiahu (Josiah) was the last righteous king before the captivity in Babylon. Note what the Tanach says about this great man:

II Melachim (Kings) 23:24-25 Moreover the workers with familiar spirits, and the wizards, and the images, and the idols, and all the abominations that were spied in the land of Judah and in Jerusalem, did Josiah put away, that he might perform the words of the law which were written in the book that Hilkiah the priest found in the house of HaShem. 25 And like unto him was there no king before him, that turned to HaShem with all his heart, and with all his soul, and with all his might, according to all the law of Moses; neither after him arose there any like him.

When we begin looking for the Mashiach, what should we be looking for? How will we recognize this individual? I believe that we should study the life of King Yoshiahu to find the traits of the Mashiach.

Yeshua

When Yeshua found His diciples asleep, he was saying the Shema. The first tractate of the Talmud speaks of a wedding feast with the question: which takes precedence, the Shema or the wedding? From this we see an allusion to the wedding feast of the Lamb. The answer to the question is that the Shema can be said any time before dawn, so that they could attend the wedding and bring joy to the bride and groom, and still say the Shema.

Mishnah (p’shat) Berakhot1:1 From what time may they recite the Shema in the evening? From the hour that the priests enter [their homes] to eat their heave offering, “until the end of the first watch”— the words of R. Eliezer. But sages say, “Until midnight.” Rabban Gamaliel says, “Until the rise of dawn.” M’H Š: His [Gamaliel’s] sons returned from a banquet hall [after midnight]. They said to him, “We did not [yet] recite the Shema.

Berakhot 1A. On what basis does the Tannaite authority stand when he begins by teaching the rule, “From what time...,” [in the assumption that the religious duty to recite the Shema has somewhere been established? In point of fact, it has not been established that people have to recite the Shema at all.][54]

Even the novice can see the point made here. The Gemara builds on the text and structure of materials already written.

How

to recite the Shema

Midrash Psalm 22:19 R. Berechiah taught in the name of R. Levi: Of Abraham, it is written The HaShem appeared unto him by the terebinths of Mamre, when he was sitting.[55] According to the ketib, the last phrase ought not to be translated “when he was sitting,” but “when he had sat down.” Thus it may be deduced that as Abraham was about to stand up, the Holy One, blessed be He, said to him: “Sit down as a model to thy children; whenever the children of Israel come into houses of prayer or into houses of study and read the Shema and pray, they also are to sit, while My Glory shall stand in their midst.” And the proof? The verse G-d standeth in the congregation of the mighty.[56]

The first line of the Shema is:

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 6:4 Hear, O Israel: HaShem our G-d HaShem is one:

Jewish law requires a greater measure of concentration on the first verse of the Shema than on the rest of the prayer. Jews commonly close their eyes or cover them with the palm of their hand while reciting it to eliminate every distraction and help them concentrate on the meaning of the words. The final word, echad, should be prolonged and emphasized. Often, the last letter of the first and last words of the Shema verse are written in larger print in the siddur. This is because these letters form the word “ed,” witness, and remind Jews of their duty to serve as witnesses to HaShem‘s sovereignty by leading exemplary lives.

The next line of the Shema originated in the ancient Temple service. When the priests recited the first verse of the Shema during the service each morning, the people, gathered in the Temple, would respond:

Blessed is the name of His Glorious Kingdom forever and ever.

This line became incorporated as the second line of the daily Shema. To indicate that it is not part of the Biblical passage of the Shema, it is said quietly, except on Yom Kippur when it is recited out loud.

The three paragraphs of the Shema, comprised of biblical verses, were also said in the daily Temple service. The first paragraph is the continuation of the Shema verse, from Devarim (Deuteronomy) 6:5-9, starting with the word “v’ahavta.” This paragraph deals with the acceptance of Divine rule. This section consists of an affirmation of belief in G-d’s unity and in His sovereignty over the world, an unconditional love of HaShem, and a commitment to the study of His teachings. It emphasizes the religious duties to love HaShem, to teach Torah to one‘s children, to talk of Torah at every possible time, to put on tefillin, and to place mezuzot on the doorpost of one‘s home.

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 6:5-9 And thou shalt love HaShem thy G-d with all thine heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy might. 6 And these words, which I command thee this day, shall be in thine heart: 7 And thou shalt teach them diligently unto thy children, and shalt talk of them when thou sittest in thine house, and when thou walkest by the way, and when thou liest down, and when thou risest up. 8 And thou shalt bind them for a sign upon thine hand, and they shall be as frontlets between thine eyes. 9 And thou shalt write them upon the posts of thy house, and on thy gates.

The second passage is from Devarim (Deuteronomy) 11:13-21, beginning with the word “v’haya.” It declares the Jews‘ acceptance of the commandments and their undertaking to carry out the commandments as evidence of their loyalty to HaShem. It talks of the fundamental principle in Jewish belief of reward and punishment that is based on the fulfillment of HaShem‘s commandments.

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 11:13-21 13 And it shall come to pass, if ye shall hearken diligently unto my commandments which I command you this day, to love HaShem your G-d, and to serve him with all your heart and with all your soul, 14 That I will give you the rain of your land in his due season, the first rain and the latter rain, that thou mayest gather in thy corn, and thy wine, and thine oil. 15 And I will send grass in thy fields for thy cattle, that thou mayest eat and be full. 16 Take heed to yourselves, that your heart be not deceived, and ye turn aside, and serve other G-ds, and worship them; 17 And then HaShem‘s wrath be kindled against you, and he shut up the heaven, that there be no rain, and that the land yield not her fruit; and lest ye perish quickly from off the good land which HaShem giveth you. 18 Therefore shall ye lay up these my words in your heart and in your soul, and bind them for a sign upon your hand, that they may be as frontlets between your eyes. 19 And ye shall teach them your children, speaking of them when thou sittest in thine house, and when thou walkest by the way, when thou liest down, and when thou risest up. 20 And thou shalt write them upon the door posts of thine house, and upon thy gates: 21 That your days may be multiplied, and the days of your children, in the land which HaShem sware unto your fathers to give them, as the days of heaven upon the earth.

The third paragraph is from BaMidbar (Numbers) 15:37-41, beginning with the word “vayomer.” It deals with the commandment of wearing tzitzith, which remind the wearer of G-d’s commandments. It mentions the exodus from Egypt, which Jews are obligated to refer to each day. The last word of the Shema, “emet” (truth) is actually part of the next blessing and is not part of the Biblical passage. It is said as part of the Shema so that one can declare, “HaShem, your G-d, is true” (Adonai eloheichem emet).

BaMidbar (Numbers) 15:37-41 And HaShem spake unto Moses, saying, 38 Speak unto the children of Israel, and bid them that they make them fringes in the borders of their garments throughout their generations, and that they put upon the fringe of the borders a ribband of blue: 39 And it shall be unto you for a fringe, that ye may look upon it, and remember all the commandments of HaShem, and do them; and that ye seek not after your own heart and your own eyes, after which ye use to go a whoring: 40 That ye may remember, and do all my commandments, and be holy unto your G-d. 41 I am HaShem your G-d, which brought you out of the land of Egypt, to be your G-d: I am HaShem your G-d. — it is true[57]

Conclusion

This prayer changes us into people who can see HaShem as ‘one‘ and who acknowledge that as ‘receivers’ they have obligations to HaShem.

We saw that Shema was the first prayer that a Jew learns. The Shema is also the last prayer that an observant Jew will say as he breathes his last breath.

So powerful is the Shema that Rabbi Akiva wanted to accept the yoke of The Kingdom as his flesh was raked with hot combs.

Chart

of forty-two

The following chart details the corellations between the places in Bamidbar (Numbers) 33, the Shema, Matthew’s genealogy, and the cities of Refuge (arei miklat):

|

Meaning |

Shema |

Shema English |

Matthew Genealogy |

42 cities of the Leviim[58] |

|

|

|

|

שמע |

Hear |

|

Golan - Passage |

|

|

|

ישראל |

Israel |

|

Ramoth - Eminences |

|

|

|

יהוה |

|

Bosor - Burning |

|

|

|

|

אלהינו |

Our G-d |

|

Kedesh - Sanctuary |

|

|

|

יהוה |

|

Shechem – Back, Shoulder |

|

|

|

|

אחד |

|

Hebron - Society |

|

|

Succoth - סכת |

Temporary Shelters |

וְאָהַבְתָּ |

And you shall love |

Yattir – A remnant |

|

|

Etham - אתם |

Contemplation |

אֵת |

|

Eshtemoa – Woman’s Bosom |

|

|

Pi Hahiroth - החירת פי |

יְהוָה |

Cholon - Sandy |

|||

|

Marah - מרה |

Bitterness |

אֱלֹהֶיךָ |

your G-d |

Judah |

Debir - word |

|

Elim - אילם |

Mighty men, Trees, Rams |

בְּכָל |

with all |

Perez |

Ayin - eye |

|

Reed Sea - סוף ים |

Reed Sea |

לְבָבְךָ |

your heart |

Hezron |

Yuttah – Turning away |

|

Sin - סין |

Desert of Clay |

וּבְכָל |

and with all |

Ram |

Beth-shemesh – House of the Sun |

|

Dophkah - דפקה |

נַפְשְׁךָ |

your soul |

Amminadab |

Gibeon - Hill |

|

|

Alush - אלוש |

Wild |

וּבְכָל |

and with all |

Nahshon |

Geba - Cup |

|

Rephidim - רפידם |

Weakness |

מְאֹדֶךָ |

your might |

Salmon |

Anathoth - Poverty |

|

Desert of Sinai - סיני מדבר |

Hatred |

וְהָיוּ |

and they shall be |

Boaz |

Almon - Hidden |

|

Kibroth Hattaavah - התאוה קברת |

Graves of Craving |

הַדְּבָרִים |

the words |

Obed |

Gezer - Dividing |

|

Chazeroth - חצרת |

Courtyard |

הָאֵלֶּה |

these |

Jesse |

Kibzaim - Congregation |

|

Rithmah - רתמה |

Smoldering |

אֲשֶׁר |

which |

David |

Beth-horon – House of Wrath |

|

Rimmon Perez - פרץ רמן |

Spreading Pomegranate Tree |

אָנֹכִי |

I |

Solomon |

Elteke – Of grace |

|

Livnah - לבנה |

White Brick |

מְצַוְּךָ |

Rehoboam |

Gibbethon – High House |

|

|

Rissah - רסה |

Well Stpped Up With Stones |

הַיּוֹם |

this day |

Abijah |

Aiyalon – Deer Field |

|

Kehelathah - קהלתה |

Assembly |

עַל |

shall be on |

Asa |

Gath-rimmon (Dan) – High wine-press |

|

Shapher - שפר |

Beautiful |

לְבָבֶךָ |

your heart |

Jehoshaphat |

Taanach – Who humbles thee |

|

Haradah - חרדה |

Terror |

וְשִׁנַּנְתָּם |

and diligently |

Jehoram |

Gath-rimmon (Mannashe) - High wine-press |

|

Makheloth - מקהלת |

Assemblies |

לְבָנֶיךָ |

you shall teach |

Uzziah |

Beeshterah – With Increase |

|

Tahath - תחת |

Bottom |

וְדִבַּרְתָּ |

and you shall speak |

Jotham |

Kishion - Hardness |

|

Terah - תרח |

Ibex |

בָּם |

of them |

Ahaz |

Dobrath - Words |

|

Mithcah - מתקה |

Sweet Delight |

בְּשִׁבְתְּךָ |

when you sit |

Hezekiah |

Yarmuth – Throwing Down |

|

Chashmonah - חשמנה |

Fruitfulness |

בְּבֵיתֶךָ |

in your house |

Manasseh |

En-gannim – Of Gardens |

|

Moseroth - מסרות |

Correction |

וּבְלֶכְתְּךָ |

and when you walk |

Amon |

Mishal – Parables, governing |

|

Bene Jaakan - יעקן בני |

Wise Son |

בַדֶּרֶךְ |

by the way |

Josiah |

Abdon - Servant |

|

Char Haggidgad - הגדגד חר |

Hole of the Cleft |

וּבְשָׁכְבְּךָ |

and when you lie down |

Jeconiah |

Helkath - Field |

|

Yotvathah - יטבתה |

Pleasantness |

וּבְקוּמֶךָ |

and when you rise up |

Shealtiel |

Rehob – Breadth, Space |

|

Avronah - עברנה |

Transitional |

וּקְשַׁרְתָּם |

and you shall bind them |

Zerubbabel |

Hammoth-dor – Hot springs generation |

|

Etzion Geber - גבר עצין |

Giant’s Backbone |

לְאוֹת |

for a sign |

Abihud |

Kartan – Two Cities |

|

Kadesh (Rekem) - קדש |

עַל |

upon |

Eliakim |

Yokneam – Building up, Possessing |

|

|

Hor - הר |

Mountain |

יָדֶךָ |

your hand |

Azor |

Kartah – Meeting, Calling |

|

Tzalmonah - צלמנה |

Shadiness |

וְהָיוּ |

and they shall be |

Zadok |

Dimnah - Dunghill |

|

Punon - פונן |

Perplexity |

לְטֹטָפֹת |

for frontlets |

Akim |

Nahalal - Pasture |

|

Oboth - אבת |

Necromancer |

בֵּין |

between |

Elihud |

Betzer – Remote Fortress |

|

Iye Abarim - העברים עיי |

Ruins of the Passes |

עֵינֶיךָ |

your eyes |

Eleazar |

Yachtzah – Trodden down |

|

Divon Gad - גד דיבן |

Sorrowing Overcomers |

וּכְתַבְתָּם |

and you shall write them |

Matthan |

Kedemot – Antiquity, Old Age |

|

Almon Diblathaim - דבלתימה עלמן |

Cake of Pressed Figs |

עַל |

on |

Mephaat – Appearance, or force, of waters |

|

|

M’Hari Abarim - מֵהָרֵי הָעֲבָרִים |

Mountains of the Passes |

מְזֻזוֹת |

the door-posts of |

||

|

Moab - מואב |

Mother’s Father |

בֵּיתֶךָ |

your house |

ben Joseph |

Cheshbon - Reckoning |

|

Beth Yeshimoth - הישמת בית |

House of The Desolaton |

וּבִשְׁעָרֶיךָ |

and on your gates. |

ben David |

Yazer – Assistance, Helper |

In this next chart, I look at the shema as a tikkun, a correction, to the journeys we took. This means that the shema is in reverse order.

|

Meaning |

Shema |

Shema English |

Matthew Genealogy |

42 cities of the Leviim[59] |

|

|

|

|

שמע |

Hear |

|

Golan - Passage |

|

|

|

ישראל |

Israel |

|

Ramoth - Eminences |

|

|

|

יהוה |

|

Bosor - Burning |

|

|

|

|

אלהינו |

Our G-d |

|

Kedesh - Sanctuary |

|

|

|

יהוה |

|

Shechem – Back, Shoulder |

|

|

|

|

אחד |

|

Hebron - Society |

|

|

Succoth - סכת |

Temporary Shelters |

וּבִשְׁעָרֶיךָ |

and on your gates. |

Yattir – A remnant |

|

|

Etham - אתם |

Contemplation |

בֵּיתֶךָ |

your house |

Eshtemoa – Woman’s Bosom |

|

|

Pi Hahiroth - החירת פי |

מְזֻזוֹת |

the door-posts of |

Cholon - Sandy |

||

|

Marah - מרה |

Bitterness |

עַל |

on |

Judah |

Debir - word |

|

Elim - אילם |

Mighty men, Trees, Rams |

וּכְתַבְתָּם |

and you shall write them |

Perez |

Ayin - eye |

|

Reed Sea - סוף ים |

Reed Sea |

עֵינֶיךָ |

your eyes |

Hezron |

Yuttah – Turning away |

|

Sin - סין |

Desert of Clay |

בֵּין |

between |

Ram |

Beth-shemesh – House of the Sun |

|

Dophkah - דפקה |

לְטֹטָפֹת |

for frontlets |

Amminadab |

Gibeon - Hill |

|

|

Alush - אלוש |

Wild |

וְהָיוּ |

and they shall be |

Nahshon |

Geba - Cup |

|

Rephidim - רפידם |

Weakness |

יָדֶךָ |

your hand |

Salmon |

Anathoth - Poverty |

|

Desert of Sinai - סיני מדבר |

Hatred |

עַל |

upon |

Boaz |

Almon - Hidden |

|

Kibroth Hattaavah - התאוה קברת |

Graves of Craving |

לְאוֹת |

for a sign |

Obed |

Gezer - Dividing |

|

Chazeroth - חצרת |

Courtyard |

וּקְשַׁרְתָּם |

and you shall bind them |

Jesse |

Kibzaim - Congregation |

|

Rithmah - רתמה |

Smoldering |

וּבְקוּמֶךָ |

and when you rise up |

David |

Beth-horon – House of Wrath |

|

Rimmon Perez - פרץ רמן |

Spreading Pomegranate Tree |

וּבְשָׁכְבְּךָ |

and when you lie down |

Solomon |

Elteke – Of grace |

|

Livnah - לבנה |

White Brick |

בַדֶּרֶךְ |

by the way |

Rehoboam |

Gibbethon – High House |

|

Rissah - רסה |

Well Stpped Up With Stones |

וּבְלֶכְתְּךָ |

and when you walk |

Abijah |

Aiyalon – Deer Field |

|

Kehelathah - קהלתה |

Assembly |

בְּבֵיתֶךָ |

in your house |

Asa |

Gath-rimmon (Dan) – High wine-press |

|

Shapher - שפר |

Beautiful |

בְּשִׁבְתְּךָ |

when you sit |

Jehoshaphat |

Taanach – Who humbles thee |

|

Haradah - חרדה |

Terror |

בָּם |

of them |

Jehoram |

Gath-rimmon (Mannashe) - High wine-press |

|

Makheloth - מקהלת |

Assemblies |

וְדִבַּרְתָּ |

and you shall speak |

Uzziah |

Beeshterah – With Increase |

|

Tahath - תחת |

Bottom |

לְבָנֶיךָ |

you shall teach |

Jotham |

Kishion - Hardness |

|

Terah - תרח |

Ibex |

וְשִׁנַּנְתָּם |

and diligently |

Ahaz |

Dobrath - Words |

|

Mithcah - מתקה |

Sweet Delight |

לְבָבֶךָ |

your heart |

Hezekiah |

Yarmuth – Throwing Down |

|

Chashmonah - חשמנה |

Fruitfulness |

עַל |

shall be on |

Manasseh |

En-gannim – Of Gardens |

|

Moseroth - מסרות |

Correction |

הַיּוֹם |

this day |

Amon |

Mishal – Parables, governing |

|

Bene Jaakan - יעקן בני |

Wise Son |

מְצַוְּךָ |

Josiah |

Abdon - Servant |

|

|

Char Haggidgad - הגדגד חר |

Hole of the Cleft |

אָנֹכִי |

I |

Jeconiah |

Helkath - Field |

|

Yotvathah - יטבתה |

Pleasantness |

אֲשֶׁר |

which |

Shealtiel |

Rehob – Breadth, Space |

|

Avronah - עברנה |

Transitional |

הָאֵלֶּה |

these |

Zerubbabel |

Hammoth-dor – Hot springs generation |

|

Etzion Geber - גבר עצין |

Giant’s Backbone |

הַדְּבָרִים |

the words |

Abihud |

Kartan – Two Cities |

|

Kadesh (Rekem) - קדש |

וְהָיוּ |

and they shall be |

Eliakim |

Yokneam – Building up, Possessing |

|

|

Hor - הר |

Mountain |

מְאֹדֶךָ |

your might |

Azor |

Kartah – Meeting, Calling |

|

Tzalmonah - צלמנה |

Shadiness |

וּבְכָל |

and with all |

Zadok |

Dimnah - Dunghill |

|

Punon - פונן |

Perplexity |

נַפְשְׁךָ |

your soul |

Akim |

Nahalal - Pasture |

|

Oboth - אבת |

Necromancer |

וּבְכָל |

and with all |

Elihud |

Betzer – Remote Fortress |

|

Iye Abarim - העברים עיי |

Ruins of the Passes |

לְבָבְךָ |

your heart |

Eleazar |

Yachtzah – Trodden down |

|

Divon Gad - גד דיבן |

Sorrowing Overcomers |

בְּכָל |

with all |

Matthan |

Kedemot – Antiquity, Old Age |

|

Almon Diblathaim - דבלתימה עלמן |

Cake of Pressed Figs |

אֱלֹהֶיךָ |

your G-d |

Mephaat – Appearance, or force, of waters |

|

|

M’Hari Abarim - מֵהָרֵי הָעֲבָרִים |

Mountains of the Passes |

יְהוָה |

|||

|

Moab - מואב |

Mother’s Father |

אֵת |

|

ben Joseph |

Cheshbon - Reckoning |

|

Beth Yeshimoth - הישמת בית |

House of The Desolaton |

וְאָהַבְתָּ |

And you shall love |

ben David |

Yazer – Assistance, Helper |

|

|

|

אחד |

|

Golan - Passage |

|

|

|

|

יהוה |

|

Ramoth - Eminences |

|

|

|

|

אלהינו |

Our G-d |

|

Bosor - Burning |

|

|

|

יהוה |

|

Kedesh - Sanctuary |

|

|

|

|

ישראל |

Israel |

|

Shechem – Back, Shoulder |

|

|

|

שמע |

Hear |

|

Hebron - Society |

* * *

This study was written by

Rabbi Dr. Hillel ben David

(Greg Killian).

Comments may be submitted to:

Rabbi Dr. Greg Killian

12210 Luckey Summit

San Antonio, TX 78252

Internet address: gkilli@aol.com

Web page: http://www.betemunah.org/

(360) 918-2905

Return to The WATCHMAN home page

Send comments to Greg Killian at his email address: gkilli@aol.com

[1] Menachoth 99b

[2] Sukkah 42a

[4] Governance of G-d

[5] An acronym for Nahmanides, also known as Rabbi Moses ben Naḥman Girondi, Bonastruc ça Porta.

[6] Yirat Shamayim – Lit. Fear of Heaven.

[7] Chazal or Ḥazal (Hebrew: חז”ל) is an acronym for the Hebrew “Ḥakhameinu Zikhronam Liv’rakha”, (חכמינו זכרונם לברכה, literally “Our Sages, may their memory be blessed”).

[8] It is well known that the sea is a remez for the fear of G-d. [As Chazal teach that the color of the sea is like that of heaven... which is like that of the throne of Glory.] That is the meaning of ‘from the great sea.’ These are the people who are great in their fear of HaShem. [Fear of HaSHem is the border.]

[9] “Service of the Heart” is a description of prayer.

[10] “Mitzva” has a nuance beyond “commandment” – its root also means connection or bond (tzavta means bond). According to our Sages, the true reward for the mitzva is simply that we have had the unique opportunity and privilege to become closer to G-d, to strengthen our bond with our Infinite Creator.

[11] Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon

[12] In Sefer HaMitzvot

[13] Lit. Kingship of Heaven

[14] Yichud carries the connotation of marital intimacy.

[15] Commentary on Sanhedrin, Chapter 10.

[16] Yoel (Joel) 2:13

[17] Berachot 9b

[18] Rashi

[19] I learned this from Hakham Dr. Yosef ben Haggai.

[20] The reading from the Prophets, on Shabbat, in the triennial cycle is called an ‘Ashlamata’ and in the annual cycle it is called the ‘haftara’.

[21] Kiddish Levana = The sanctification of the new moon.

[22] Simcha = joy.

[23] Geulah = Redemption

[24] A more accurate name for the New Testament.

[25] Berachot 28b

[26] Vayikra (Leviticus) 1:1

[27] Devarim (Deuteronomy) 6:4-9, 11:13-21, Bamidbar (Numbers) 15:37-41

[28] Gan Eden = Garden of Eden.

[29] The first paragraph of the Shema.

[30] All of the Jews.

[31] Debarim (Deuteronomy) 6:4

[32] Debarim (Deuteronomy) 6:9

[33] Debarim (Deuteronomy) 6:4-9

[34] Ohev Yisrael

[35] Orach Chaim 61:3

[36] Shliach Tzibbur lit. Angel of the Congregation, usually refers to the Cantor of the congregation.

[37] This is the Sefardi custom.

[38] This is the Ashkenazi custom.

[39] Devarim (Deuteronomy) 6:4ff

[40] Rashi

[41] see Mishnah Berurah 155:4

[42] Kovetz Shiurim, Vol. 2, no. 11

[43] Mishneh Torah, Laws of Torah Study 1:8

[44] Torat Ha’odom

[45] The Torah contains no minimum requirement for Torah study.

[46] Shulchan Aruch Harav 3:6

[47] Who ruled that if the old Shewbread was on the table for some time in the morning and the new for some time in the evening, that can be said to be ‘continually’.

[48] Yehoshua (Joshua) 1:8

[49] The passage commencing ‘Hear, O Israel’ (Devarim 6:4ff).

[50] Plur. ‘of ‘am ha-arez, v. Glos. Such a pronouncement might deter the common people from educating their children in the study of the Torah, seeing that the Scriptural precept is fulfilled by the twice daily recital of the Shema’.

[51] For they would argue thus: if merely for the recital of the Shema’ twice daily the reward is offered: ‘Then thou shalt make thy ways prosperous and then thou shalt have good success’ (Yehoshua ibid.), how great shall be the reward for those that devote their whole time to the study of the Torah!

[52] Rambam (Hilchot Keriyat Shema 1:2:3)

[53] The “old Testament”.

[54] II Luqas (Acts) 7:58

[55] Bereshit (Genesis) 18:1

[56] Tehillim (Psalms) 82:1

[57] Although the word “true,” belongs to the next paragraph, it is appended to the conclusion of the previous one.

[58] Yehoshua (Joshua) chapter 21

[59] Yehoshua (Joshua) chapter 21