![]()

By Rabbi Dr. Hillel ben David (Greg Killian)

Pshat - The Thirty-two Rules of Eliezer B. Jose Ha-Ge-lili

Remez - The Seven Rules of Hillel

Drash - The Thirteen rules of Rabbi Ishmael

![]()

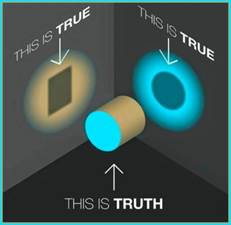

The Torah is understood and interpreted according to the level being discussed. The Torah can be understood on four levels, while other writings may be confined to only one level. For example, Bereshit (the book of Genesis) can be understood on all four levels, while the Midrash and sefer Matitiyahu (Matthew) can only be understood on the drash level. The following chart details these four levels.

|

פרדס |

פשאת |

רמס |

דרש |

סוד |

|

Pshat |

Derash |

|||

|

Definition |

Simple |

Hint |

Explore - Ask |

|

|

Literary level |

Grammatical |

Allegory |

Parabolic |

Mystical |

|

Audience level |

Common People |

Noble (Lawyers, Judges, Scientists) |

Kingly (civil servants, political scientists) |

Mystic (psychologists) |

|

Hermeneutic level[1] |

7 Hillel Laws |

13 Ishmael Laws |

32 Ben Gallil Laws |

|

|

Rabbinic level |

||||

|

Marqos (Mark), 1 & 2 Peter |

I and II Luqas (Luke) |

Matityahu (Matthew) |

Yochanan (John) 1, 2, 3, and Revelation |

|

|

Presentation |

HaShem’s Servant |

Son of Man |

The King |

Son of G-D |

|

Principle Concern |

What do we have to do? |

What is the meaning behind what we have to do? |

How do we go about establishing HaShem's Kingdom on earth? |

What metaphysical meaning is there to what is happening? |

|

Asiyah |

Yetzirah |

Beriyah |

Atzilut |

|

|

Symbol |

Man |

Ox/Bull |

Lion |

Eagle |

|

Mazzaroth |

Deli |

Shaur |

Aryeh |

Aqurav |

|

Reuben |

Ephraim |

Judah |

Dan |

|

|

Outside Chatzer |

Chatzer |

Kodesh |

Kodesh Kodashim |

|

|

Mikrah Megillah |

Matanot L’Evyonim |

Mishloach Manot |

Seudas Purim |

For a geater explanation for these four levels, look at the study titled: REMEZ. Each of these four levels has its own rules for proper interpretation. The rest of this paper deals with the details of these rules.

Pshat - The Seven Rules of Hillel[2]

1. Kal Va-Chomer:

Argument that reasons: If a rule or fact applies in a situation where there is relatively little reason for it to apply, certainly it applies in a situation where there is more reason for it to apply. For example, in the verse: Moses says, “If Israel, for whom my message is beneficial, will not listen to me, certainly Pharaoh, for whom the message is detrimental, will not listen” (Mizrachi; Sifsei Chachamim).

Another reason that Pharaoh would not listen is because Moses was “of blocked lips”, and it is unbefitting that one with a speech defect should speak before the king. However, to the general populace such an impediment is not significant. So, if the Israelites who should not have demurred because of Moses’ blocked lips, nevertheless ignored him, certainly Pharaoh, who was unused to such speech, would reject his message. Thus, the statement, “I am of blocked lips”, is part of the val vachomer. And it is to emphasize this that Rashi commented on “blocked lips” before “So how will Pharaoh listen to me?” (Gur Aryeh)

Midrash Rabbah - Genesis XCII:7 AND WHEN THEY WERE GONE OUT OF THE CITY... IS NOT THIS IT IN WHICH MY LORD DRINKETH... AND HE OVERTOOK THEM... AND THEY SAID UNTO HIM:... BEHOLD, THE MONEY, etc. (XLIV, 4-8). R. Ishmael taught: This is one of the ten a fortiori arguments recorded in the Torah. (i) BEHOLD, THE MONEY, WHICH WE FOUND IN OUR SACKS’ MOUTHS, WE BROUGHT BACK UNTO THEE; does it then not stand to reason, How THEN SHOULD WE STEAL, etc. (ii) Behold, the children of Israel have not hearkened unto me; surely all the more, How then shall Pharaoh hear me.[3] (iii) Behold, while I am yet alive with you this day, ye have been rebellious against the Lord; does it not follow then, And how much more after my death.[4] (iv) And the Lord said unto Moses: If her father had but spit in her face; surely it would stand to reason, Should she not hide in shame seven days.[5] (v) If thou hast run with the footmen, and they have wearied thee, is it not logical to say, Then how canst thou contend with horses.[6] (vi) Behold, we are afraid here in Judah; surely it stands to reason, How much more then if we go to Keilah.[7] (vii) And if in a land of Peace where thou art secure [thou art overcome], is it not logical to ask, How wilt thou do in the thickets of the Jordan? Jer. loc. cit.). (viii) Behold, the righteous shall be requited in the earth; does it not follow, How much more the wicked and the sinner.[8] (ix) And the king said unto Esther the queen: The Jews have slain and destroyed five hundred men in Shushan the castle; it stands to reason, What then have they done in the rest of the king's provinces.[9] (x) Behold, when it was whole, it was meet for no work; surely it is logical to argue, How much less, when the fire hath devoured it, and it is singed, etc.[10])

Rashi’s Commentary for: D’barim (Deut.) 32:46 Set your hearts A person must direct his eyes, his heart, and his ears to the words of the Torah, for Scripture states (Ezek. 40:4),"Son of man, see with your eyes, and listen with your ears, and set your heart [upon all that I show you]" [namely, the plan of the Holy Temple]. Now, here, we have an inference from major to minor: If in the case of the plan of the Holy Temple, which is visible to the eyes and which is measured with a measuring-rod, a person must direct his eyes, ears, and heart to understand, how much more so must he do so to understand the words of the Torah, which are likened to “mountains suspended by a hair” [i.e., numerous laws derived from a single word of the Torah]?![11]

There are ten val chomer arguments, enumerated in Bereshit Rabbah 92:7, that appear in Torah, as cited by Rashi:

Genesis 44:8

Exodus 6:12

Numbers 12:14

Deuteronomy 31:27

I Samuel 23:3

Jeremiah 12:5 (2 arguments)

Ezekiel 15:5

Proverbs 11:31

Esther 9:12

2. Gezerah shawah:

Argument from analagy. Biblical passages containing synonyms or homonyms are subject, however much they differ in other respects, to identical definitions and applications.

3. Binyan ab mi-katub ehad: Application of a provision found in one passage only to passages which are related to the first in content but do not contain the provision in question.

4. Binyan ab mi-shene ketubim: The same as the preceeding except that the provision is generalized from two Biblical passages.

5. Kelal u-Perat and Perat u-kelal: Definition of the general by the particular, and of the particular, and of the particular by the general.

6. Ka-yoze bo mi-makon aher: Similarity in context to another scriptural passage.

7. Dabar ha-lamed me-‘inyano: Interpretation deduced from the context.

* * *

Remez - The Thirty-two Rules of Eliezer B. Jose Ha-Ge-lili[12]

Rules laid down by R. Eliezer b. Jose Ha-Gelili for haggadic exgesis, many of them being applied also to halachic interpretation.

1. Ribbuy (extension): The particles “et”, “gam”, and “af”, which are superfluous indicate that something which is not explicitly stated must be regarded as included in the passage under consideration, or that some teaching is implied thereby.

2. Mi’ut (limitation): The particles “ak”, “rak”, and “min”, indicate that something implied by the concept under consideration must be excluded in a specific case.

3. Ribbuy ahar ribbuy (extension after extension): When one extension follows another it indicates that more must be regarded as implied.

4. Mi’ut ahar mi’ut (limitation after limitation): A double limitation indicates that more is to be omitted.

5. Kal va-chomer meforash: “Argumentum a minori ad majus”, or vice versa, and expressly so characterized in the text.

6. Kal va-chomer satum: “Argumentum a minori ad majus” or vice versa, but only implied, not explicitly declared to be one in the text. This and the preceeding rule are contained in the Rules of Hillel number 1.

7. Gezerah shawah: Argument from analagy. Biblical passages containing synonyms or homonyms are subject, however much they differ in other respects, to identical definitions and applications.

Rashi’s Commentary for: Shemot (Exod.) 34:20 and they shall not appear before Me empty-handed According to the simple meaning of the verse, this is a separate matter [from the rest of this verse] and is unrelated to the firstborn, because there is no obligation to appear [in the Temple] in the commandment dealing with the firstborn. Instead this is another warning, [meaning] and when you ascend [to the Temple] on the festivals, you shall not appear before Me empty-handed, [but] it is incumbent upon you to bring burnt offerings (Chag. 7a) whenever appearing before God. According to the way it is interpreted by a Baraitha, this is a superfluous verse [for this was already stated in Exod. 23:15], and it is free [i.e., has no additional reason for being here other than] to be used for a גְּזֵרָה שָׁוָה , [i.e.,] an instance of similar wording, to teach [us] about the provisions given a Hebrew slave [when he is freed]—that it is five selas from each kind [i.e., of sheep, grain, and wine], as much as the redemption of a firstborn. [This is elaborated upon] in tractate Kiddushin (17a).

8. Binyan ab mi-katub ehad: Application of a provision found in one passage only to passages which are related to the first in content but do not contain the provision in question.

9. Derek Kezarah: Abbreviation is sometimes used in the text when the subject of discussion is self-explanatory.

10. Dabar shehu shanuy (repeated expression): Repitition implies a special meaning.

11. Siddur she-nehlak: Where in the text a clause or sentence not logically divisible is divided by the punctuation, the proper order and the division of the verses must be restored according to the logical connection.

12. Anything introduced as a comparison to illustrate and explain something else itself receives in this way a better explanation and elucidation.

13. When the general is followed by the particular, the latter is specific to the former and merely defines it more exactly. (compare with Hillel #5)

Rashi on Bereshit (Genesis) 2:8 from the east Heb. מִקֶּדֶם . In the east of Eden, He planted the garden (Midrash Konen). Now if you ask: It has already been stated (above 1:27): “And He created man, etc.!” I saw in the Baraitha of Rabbi Eliezer the son of Rabbi Jose the Galilean concerning the thirty-two principles by which the Torah is expounded, and this is one of them [method 13]: A general statement followed by a specific act, the latter constitutes a specific [clarification] of the first [general statement]. “And He created man.” This is a general statement. It left obscure whence he was created, and it left His deeds obscure [i.e., how God created man]. The text repeats and explains: “And the Lord God formed, etc.,” and He made the Garden of Eden grow for him, and He placed him in the Garden of Eden, and He caused a deep sleep to fall upon him. The listener may think that this is another story, but it is only the detailed account of the former. Likewise, in the case of the animal, Scripture repeats and writes (below verse 19): “And the Lord God formed from the ground all the beasts of the field,” in order to explain, “and He brought [them] to man” to name them, and to teach about the fowl, that they were created from the mud.

14. Something important is compared with something unimportant to elucidate it and render it more readily intelligible.

15. When two Biblical passages contradict each other the contradiction in question must be solved by reference to a third passage.

16. Dabar meyuhad bi-mekomo: An expression which occurs in only one passage can be explained only by the context. This must have been the original meaning of the rule, although another explanation is given in the examples cited in the baraita.

17. A point which is not clearly explained in the main passage may be better elucidated in another passage.

18. A statement with regard to a part may imply the whole.

19. A statement concerning one thing may hold good with regard to another as well.

20. A stetment concerning one thing may apply only to something else.

21. If one object is compared to two other objects the best part of both the latter forms the tertium quid of comparison.

22. A passage may be supplemented and explained by a parallel passage.

23. A passage serves to elucidate and supplement its parallel passage.

24. When the specific implied in the general is especially excepted from the general, it serves to emphasize some property characterizing the specific.

25. The specific implied in the general is frequently excepted from the general to elucidate some other specific property, and to develop some special teaching concerning it.

26. Mashal (parable).

27. Mi-ma’al: Interpretation through the preceding.

28. Mi-neged: Interpretation through the opposite.

29. Gematria: Interpretation according to the numerical value of the letters.

30. Notarikon: Interpretation by dividing a word into two or more parts.

31. Postposition of the precedent. Many phraes which follow must be regarded as properly preceding, and must be interpreted accordingly in exegesis.

32. May portions of the Bible refer to an earlier period than to the sections which precede them, and vice versa.

These thirty-two rules are united in the so-called Baraita of R. Eliezer b. Jose HaGelili. In the introduction to the Midrash ha-Gadole, where this baraita is given, it contains thirty-three rules. Rule 29 being divided into three, and rule 27 being omitted.

Drash - The Thirteen rules of Rabbi Ishmael

Thirteen rules compiled by Rabbi Ishmael b. Elisha for the elucidation of the Torah and for making halachic deductions from it. They are, strictly speaking, mere amplifications of the seven rules of Hillel, and are collected in the Baraita of R. Ishmael, forming the introduction to the Sifra and reading as follows:

1. Kal VaChomer: From a lenient law to a strict law. (Identical with the first rule of Hillel.)

A kal vachomer is an a fortiori logical argument that reasons: If a rule or fact applies in a situation where there is relatively little reason for it to apply, certainly it applies in a situation where there is more reason for it to apply. For example, in the verse: Moses says, “If Israel, for whom my message is beneficial, will not listen to me, certainly Pharaoh, for whom the message is detrimental, will not listen”.[13]

Another reason that Pharaoh would not listen is because Moses was “of blocked lips”, and it is unbefitting that one with a speech defect should speak before the king. However, to the general populace such an impediment is not significant. So, if the Israelites who should not have demurred because of Moses’ blocked lips, nevertheless ignored him, certainly Pharaoh, who was unused to such speech, would reject his message. Thus, the statement, “I am of blocked lips”, is part of the val vachomer. And it is to emphasize this that Rashi commented on “blocked lips” before “So how will Pharaoh listen to me?” [14]

If, for example, a certain act is forbidden on an ordinary festival, it is so much more forbidden on Yom HaKippurim. If a certain act is permissable on Yom HaKippurim, it is so much more permissable on an ordinary festival.

If a tamid offering may be offered on Shabbat, even though if it is not brought there is no punishment of keret (a divine punishment of premature death) involved, then certainally the Pesach offering may be offered on Shabbat, since if it is not brought there is a punishment of keret involved.

If it is forbidden to pluck an apple from a tree on festivals (when food may be prepared by cooking and other means that may be prohibited on Shabbat), surely plucking is forbidden on Shabbat. Conversely, if it is permitted to slice vegetables on Shabbat, it is surely permitted on the festivals.

The reverse is also true, if a lenient ruling applies to a stringent law, then certainally that lenient ruling applies to a lenient law.

Rashi uses Devarim (Deuteronomy) 14:8 to illustrate this:

8 nor touch their carcass Our Rabbis explained [that this refers only to] the Festival[s], for a person is obliged to purify himself for the Festival. One might think that [all Israelites] are prohibited [from touching a carcass] during the entire year. Therefore, Scripture states [in reference to the uncleanness of a corpse], “Say to the kohanim... [none shall be defiled for the dead...]” (Lev. 21:1). Now if in the case of the uncleanness caused by a [human] corpse, which is a stringent [kind of uncleanness, only] kohanim are prohibited regarding it but [ordinary] Israelites are not prohibited, then in the case of uncleanness caused by a carcass [of an animal], which is light [i.e., a less stringent uncleanness], how much more so [is the case that ordinary Israelites are permitted to touch these carcasses]!

Rashi, on Bamidbar (Numbers) 12:14, says: 14 If her father were to spit in her face If her father had turned to her with an angry face, would she not be humiliated for seven days? All the more so in the case of the Divine Presence [she should be humiliated for] fourteen days! But [there is a rule that] it is sufficient that a law derived from an afortiori conclusion to be only as stringent as the law from which it is derived. Thus, even as a consequence of My reprimand, she should be confined [only] seven days.-[Sifrei Beha’alothecha 1:42:14, B.K. 25a]

2. Gezerah shavah: From a similarity of words. (Identical with the second rule of Hillel.)

Argument from analagy. Biblical passages containing synonyms or homonyms are subject, however much they differ in other respects, to identical definitions and applications.

If a similar word or expression occurs in two places in scripture, the rulings of each place may be applied to the other. “Similar words” cannot be original; it must be passed from master to disciple, originating with Moshe to whom HaShem taught at Mount Sinai.

In strictly limited cases, the Sinaitic tradition teaches that the two independent laws or cases are meant to shed light upon one another. The indication that the two laws are complementary can be seen in two ways: (a) The same or similar words appear in both cases, e.g. the word in its proper time,[15] is understood to indicate that the daily offering must be brought even on Shabbat. Similarly, the same word in the context of the Pesach offering[16] should be interpreted to mean that it is offered even if its appointed day, too, falls on Shabbat[17] When two different topics are placed next to one another (this is also called comparison), e.g. many laws regarding the technical process of divorce and betrothal are derived from one another because Scripture[18] mentions divorce and betrothal in the same phrase by saying, she shall depart [through divorce] and become betrothed to another man. This juxtaposition iumplies that the two changes of marital status are accomplished through similar legal processes.[19]

The phrase ‘Hebrew slave”[20] is ambiguous, for it may mean a heathen slave owned by a Hebrew, or else, a slave who is a Hebrew. That the latter is the correct meaning is proved by a reference to the phrase “your Hebrew brother”[21], where the same law is mentioned (… If your Hebrew brother is sold to you …).

Rashi’s Commentary for: Vayiqra (Leviticus) 13:55: the worn Heb. בְּקָרַחְתּוֹ. Old, worn out garments, and because of the midrashic explanation, that this language is necessary for a גְּזֵרָה שָׁוָה here [i.e., a link between two seemingly unrelated passages through common terms, thereby inferring the laws of one passage from the laws of the other, as follows]: How do we know that if a lesion on a garment spreads [throughout the entire garment], it is clean? Because [Scripture] states קָרַחַת and גַּבַּחַת in the context of [lesions that appear on] man (verse 42), and here, in the context of [lesion on] garments, [Scripture] also states קָרַחַת and גַּבַּחַת ; just as there [in the case of lesions on man], if it spread over the entire body, he is clean (verses 1213), so too, here, [in the case of lesion on garments,] if it spread over the entire garment, it is clean (San. 88a), Scripture adopts the [unusual] expressions קָרַחַת and גַּבַּחַת. However, concerning the explanation and translation [of these terms], the simple meaning is that קָרַחַת means “old” and גַּבַּחַת means “new.” It is as though it were written, “[It is a lesion on] its end or its beginning,” for קָרַחַת means “back” [i.e., at the end of the garment’s life, when it is old,] and גַּבַּחַת means “front” [i.e., the beginning of its life, when it is new]. This is just as is written, “And if [he loses hair] at the front of his head, [he is bald at the front (גַּבַּח)]” (verse 41). And קָרַחַתrefers from the crown toward his back. Thus it is explained in Torath Kohanim (13: 144).

3. Binyan Ab: From a general principle found in one verse, or from a general principle found in two verses. (This rule is a combination of the third and fourth rules of Hillel.)

Rules deduced from a single passaage of Scripture and rules deduced from two passages.

The Torah teaches that work in preparation of food is permitted on Pesach. We extend this ruling to apply to other holidays as well.

Where one verse may not be sufficient to apply its rule elsewhere, a combination of two verses might be. For example: The Torah holds the owner of an ox liable for the damages caused by the ox. This ruling applies even if the damages it inflicts occurred somewhere other than where the owner originally placed the ox. Similarly, one is liable for the damages caused by a pit he dug, or by an inanimate obstacle he placed in a public domain. From the combination of these two laws we derive a third law that if a person places an obstacle in the public domain and it caused damage somewhere other than where it was originally placed, the person who originally put it down is liable. See Bava Kama 6a.

From Devarim 24:6 (“No one shall take a handmill or an upper millstone in pledge, for he would be taking a life in pledge”) the Rabbis concluded: “Everything which is used for preparing food is forbidden to be taken in pledge”.

From Shemot 21:26-27 (“If a man strikes the eye of his slave … and destroys it, he must let him go free in compensation for his eye. If he knocks out the tooth of his slave … he must let him go free…”) the Hakhamim concluded that when any part of the slave’s body is mutilated by the master, the slave shall go free.

Since the Torah specifies that one may not marry even his maternal half sister, this general principle, dictates that the prohhibition against marrying ones father’s sister applies equally to his father’s maternal half sister.[22] the same rule applies when two different verses shed light on one another: Similar situations may be derived from the combination of the two verses.

* * *

Let’s continue with the word “grace” (חןֵ) appearing in parashat Ki Tisa. In the Third Aliyah (Exodus 33:12-16), Moshe Rabbeinu asks HaShem to show him his ways. There are 82 words in this parshiyah. It is after the sin of the Golden Calf. In these 82 words, Moshe asks four times, “If I have found favor in your eyes”. This is the highest concentrations of the word “grace”, or “favor” in the Tanach. This is the source for our method of counting the location of words in a paragraph or in a verse. This is the binyan av for this method, and when you see it once very strongly, from then on you believe that the Torah has this in mind.

4. Kelal uPerat: From a generality followed by a specific.

The general and the particular.

In Vayikra (Leviticus) (Leviticus) 18:6 the law reads: “None of you shall marry anyone related to him”. This generalization is followed by a specification of forbidden marriages. Hence, this prohibition applies only to those expressly mentioned.

The Torah writes,[23] If a person shall offer a sacrifice to HaShem of an animal, etc. The generalization of an animal would seem to include any and all animals. However, Scripture follows that phrase with, from cattle or sheep, thereby specifying that only cattle and sheep are fit to be brought as offerings.

Rashi’s Commentary on D’barim (Deuteronomy) 15:21 [And if there be any] blemish [in it] [This is] a כְּלָל, a general statement [not limiting itself to anything in particular].

lame, or blind [This is] a פְּרָט, particular things, [limiting the matter to these things].

any ill blemish [Once again the verse] reverts to כְּלָל, a general statement. [Now we have learned that when a verse expresses a כְּלָל, then a פְּרָט, and then a כְּלָלagain, just as in this case, we apply the characteristics of the פְּרָט to the whole matter.] Just as the blemishes detailed [lame or blind] are externally visible blemishes that do not heal, so too, any externally visible blemish that does not heal [renders a firstborn animal unfit for sacrifice and may be eaten as ordinary flesh].-[Bech. 37a]

Rashi’s Commentary on D’barim (Deuteronomy) 16:8 For six days you shall eat matzoth But elsewhere it says, “For seven days [you shall eat matzoth]!” (Exod. 12:15). [The solution is:] For seven days you shall eat matzoth from the old [produce] and six days [i.e., the last six days, after the omer has been offered] you may eat matzoth prepared from the new [crop]. Another explanation: It teaches that the eating of matzoh on the seventh day of Passover is not obligatory, and from here you learn [that the same law applies] to the other six days [of the Festival], For the seventh day was included in a general statement [in the verse “For seven days you shall eat matzoth,” but in the verse: “Six days you shall eat matzoth ”] it has been taken out of this general [statement], to teach us that eating matzoh [on the seventh day] is not obligatory, but optional. [Now we have aready learned that if something is singled out of a general statement, we apply the relevant principle not only to itself but to every thing included in the general category. Thus the seventh day] is excluded here not to teach regarding itself, rather to teach regarding the entire generalization [i.e., the entire seven days of the Festival]. Just as on the seventh day the eating of matzah is optional, so too, on all the other days, the eating of matzah is optional. The only exception is the first night [of Passover], which Scripture has explicitly established as obligatory, as it is said, “in the evening, you shall eat matzoth ” (Exod. 12:18). -[Mechilta on Exod 12:18; Pes. 120a]

5. uPerat ukelal: From a specific followed by a generality.

The particular and the general.

In Shemot 22:9 we read: “If a man gives to his neighbor an ass, an ox, or a sheep, to keep, or any animal, and it dies...”. The general phrase “any animal”, which follows the specification, includes is this law all kinds of animals.

Regarding the mitzva of returning a lost article, the Torah writes[24] so shall you do for his donkey and so shall you do for his garment. One might conclude that the mitzva applies only to these items. The Torah therefore follows that phrase with so shall you do regarding any lost article of your brother, thereby including all lost aticles in the mitzva.

6. Kelal uPerat ukelal (The general, the particular, and the general): When a generality is followed by a specific and a generality, you may infer only that which is similar to the specific.

In Shemot 22:8 we are told that an embezzler shall pay double to his neighbor “for anything embezzled [generalization], for ox, or ass, or sheep, or clothing [specification], or any article lost [generalization]. Since the specification includes only moveable property, and objects of intrinsic value, the fine of double payment does not apply to embezzled real estate, not to notes and bills since the latter represents only a symbolic value.

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 14:26 Other things than those specified in Devarim 14:26 may be purchased, but only if they are food or drink like those specified.

As an example, Rashi says:

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 14:26 [And you will turn that money] into whatever your soul desires This is a כְּלָל , a general statement [not limited to anything in particular. Whereas the next expression,]

cattle, or sheep, new wine or old wine [represents a] פְּרָט , a “specification” [that is, it details particular things, limiting the matter to those things. After this, the verse continues,]

or whatever your soul desires [The verse] again reverts to a כְּלָל , a “general statement.” [Now we have learned that when a verse expresses a כְּלָל , a פְּרָט , and then a כְּלָל again, as in this case, we apply the characteristics of the פְּרָט to the whole matter. That is,] just as the items listed in the פְּרָט 1) are products of things themselves produced by the earth [e.g., wine comes from grapes], and 2) are fitting to be food for man, [so must the money replacing them be used to purchase such products].-[Eruvin 27a]

Another example, Rashi says:

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 14:26 [And you will turn that money] into whatever your soul desires This is a כְּלָל , a general statement [not limited to anything in particular. Whereas the next expression,]

cattle, or sheep, new wine or old wine [represents a] פְּרָט , a “specification” [that is, it details particular things, limiting the matter to those things. After this, the verse continues,]

or whatever your soul desires [The verse] again reverts to a כְּלָל , a “general statement.” [Now we have learned that when a verse expresses a כְּלָל , a פְּרָט , and then a כְּלָל again, as in this case, we apply the characteristics of the פְּרָט to the whole matter. That is,] just as the items listed in the פְּרָט 1) are products of things themselves produced by the earth [e.g., wine comes from grapes], and 2) are fitting to be food for man, [so must the money replacing them be used to purchase such products].-[Eruvin 27a]

Another example, Rashi says:

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 15:21 [And if there be any] blemish [in it] [This is] a כְּלָל, a general statement [not limiting itself to anything in particular].

lame, or blind [This is] a פְּרָט, particular things, [limiting the matter to these things].

any ill blemish [Once again the verse] reverts to כְּלָל, a general statement. [Now we have learned that when a verse expresses a כְּלָל, then a פְּרָט, and then a כְּלָל again, just as in this case, we apply the characteristics of the פְּרָט to the whole matter.] Just as the blemishes detailed [lame or blind] are externally visible blemishes that do not heal, so too, any externally visible blemish that does not heal [renders a firstborn animal unfit for sacrifice and may be eaten as ordinary flesh].-[Bech. 37a]

Another example, Rashi says:

Devarim 16:8 For six days you shall eat matzoth But elsewhere it says, “For seven days [you shall eat matzoth]!” (Exod. 12:15). [The solution is:] For seven days you shall eat matzoth from the old [produce] and six days [i.e., the last six days, after the omer has been offered] you may eat matzoth prepared from the new [crop]. Another explanation: It teaches that the eating of matzoh on the seventh day of Passover is not obligatory, and from here you learn [that the same law applies] to the other six days [of the Festival], For the seventh day was included in a general statement [in the verse “For seven days you shall eat matzoth,” but in the verse: “Six days you shall eat matzoth ”] it has been taken out of this general [statement], to teach us that eating matzoh [on the seventh day] is not obligatory, but optional. [Now we have aready learned that if something is singled out of a general statement, we apply the relevant principle not only to itself but to every thing included in the general category. Thus the seventh day] is excluded here not to teach regarding itself, rather to teach regarding the entire generalization [i.e., the entire seven days of the Festival]. Just as on the seventh day the eating of matzah is optional, so too, on all the other days, the eating of matzah is optional. The only exception is the first night [of Passover], which Scripture has explicitly established as obligatory, as it is said, “in the evening, you shall eat matzoth ” (Exod. 12:18). -[Mechilta on Exod 12:18; Pes. 120a]

7. kelal shehu tzerik lefrat: From a generality that requires an explanatory specific, and from a specific that requires an explanatory generality.

The general which requires elucidation by the particular, and the particular which requires elucidation by the general.

The Torah writes[25] Sanctify to me any firstborn, which implies that even a female firstborn would be included in this law. The Torah therefore explicitly states that included in this law are only males (v.12). The previous employs derivation method #4; what follows employs method #7, see Rashi to tractate Bechorot 19a. However, one might still think that a firstborn male, even if preceded by females, is to be sanctified. The Torah therefore says (v.2) the first to leave the womb. However, one might still think that if a male is the first to leave the womb, even if it was preceded by one born by caesarean section, it is to be sanctified. The verse therefore states: Firstborn. Thus, it must be a male and the absolute firstborn if it is to be sanctified. Hence, we have an illustration of a generality (firstborn) that requires a specific (the first to leave the womb) to define it, and vice versa.

In Vayikra (Leviticus) (Leviticus) 17:13 we read: “He shall pour out its blood and cover it with dust”. The verb “to cover” is a general term, since there are various ways of covering a thing; “with dust” is specific. If we were to apply rule four to this passage, the law would be that the blood of the slaughtered animal must be covered with nothing except duct. Since, however, the general term “to cover” may also mean “to hide”, our present passage necessarily requires the specific expression “with dust”; otherwise the law might be interpreted to mean the blood is to be concealed in a closed vessle. On the other hand, the specification “with dust” without the general expression “to cover” would be meaningless.

8. Anything that was part of a general principle and was later singled out from the general principle to teach [a specific piece of information], it is not to teach [this information] only about itself that it was singled out, but to teach [this information] regarding the entire general principle was it singled out.

The particular implied in the general and excepted from it for pedagogic purposes elucidates the general as well as the particular.

The Torah writes,[26] Do not kindle a fire in all your habitation on the Shabbat day. Now kindling is included in the general category of work prohibited on Shabbat. Why then is it singled out with its own verse? It is singled out in order to compare the other to kindling, that just as when one kindles on Shabbat unintentionally he must bring a sin offering as atonement for that one action, so, if one performes several labors prohibited on Shabbat unintentionally, he is required to bring a separate sin offering for each and every one. Hence, the specific law teaches something with regard to the general law.

In Devarim (Deuteronomy) 22:1 we are told that the finder of lost property must return it to its owner. In the next verse the Torah adds: “You shall do the same … with his garment and with anything lost by your brother… which you have found …”. Garment, though included in the general expression “anything lost”, is specifically mentioned in order to indicate that the duty to announce the finding of lost articles applies only to such objects which are likely to have an owner, and which have, as in the case of clothing, some marks by which they can be identified.

The Torah[27] forbids the eating of sacrificial meat by anyone who is ritually contaminated. The very next verse singles out the peace-offering, and states that a contaminated person who eats of it is liable to keret, spiritual excision. This principle teaches that the peace-offering is not an exception to the the general rule; rather that the punishment specified for the peace-offering applies to all offerings.

"A man, also, or a woman that devines that by a ghost or a familiar spirit, shall surel be put to death; they shall stone them with stones"[28] Divination by a ghost or a familiar spirit is included in the general rule against witchcraft.[29] Since the penalty in Vayikra (Leviticus) 20:27 is stoneing it may be inferred that the same penalty applies to other instasnces within the same general rule.[30]

Rashi, in his commentary for: Shemot (Exodus) 12:15, provides us with another example of this principle:

Shemot (Exodus) 12:15 For seven days-Heb. שִׁבְעַת יָמִים , seteyne of days, i.e., a group of seven days.[31]

For seven days you shall eat unleavened cakes- But elsewhere it says: “For six days you shall eat unleavened cakes”.[32] This teaches [us] regarding the seventh day of Passover, that it is not obligatory to eat matzah, as long as one does not eat chametz. How do we know that [the first] six [days] are also optional [concerning eating matzah]? This is a principle in [interpreting] the Torah: Anything that was included in a generalization [in the Torah] and was excluded from that generalization [in the Torah] to teach [something] it was not excluded to teach [only] about itself, but it was excluded to teach about the entire generalization. [In this case it means that] just as [on] the seventh day [eating matzah] is optional, so is it optional in [the first] six [days]. I might think that [on] the first night it is also optional. Therefore, Scripture states: “in the evening, you shall eat unleavened cakes”.[33] The text established it as an obligation.[34]

but on the preceding day you shall clear away all leaven-Heb. בַּיוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן . On the day before the holiday; it is called the first [day], because it is before the seven; [i.e., it is not the first of the seven days]. Indeed, we find [anything that is] the preceding one [is] called רִאשׁוֹן , e.g.,הֲרִאשׁוֹן אָדָם תִּוָלֵד , “Were you born before Adam?”.[35] Or perhaps it means only the first of the seven [days of Passover]. Therefore, Scripture states: “You shall not slaughter with leaven [the blood of My sacrifice]”.[36] You shall not slaughter the Passover sacrifice as long as the leaven still exists.[37] [Since the Passover sacrifice may be slaughtered immediately after noon on the fourteenth day of Nissan, clearly the leaven must be removed before that time. Hence the expression בַּיוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן must refer to the day preceding the festival.]

9. Anything that was part of a general principle and was later singled out to discuss another point similar to [the general principle] was singled out in order to be more lenient, but not to be more stingent.

The particular implied in the general and excepted from it on account of the special regulation which corresponds in concept to the general, is thus isolated to decrease rather than to increase the rigidity of its application.

The Torah says[38] One who kills a person shall be put to death. This verse would seem to mandate the death penalty both for one who kills intentionally and also for one who kills unintentionally. The Torah then writes (v.13) that if one kills another person unintentionally, he is not put to death; rather, he is exiled to one of the cities of refuge (Devarim 19:5), One who kills unintentionally is thereby singled out from the general principle of one who kills a person shall be put to death, to indicate that his punishment is more lenient, and he is not subject to death, merely to exile.

In Shemot 35:2-3 we read: “Whoever does any work on the Sabbath shall be put to death; you shall not light a fire on the Sabbath day”. The law against lighting a fire on the Sabbath, though already implied in “any work”, is mentioned separately in order to indicate that the penalty for lighting a fire on the Sabbath is not as drastic.

The law of the boil[39] and the burn[40] are treated specifically even though these are specific instances of the general rule regarding plague spots.[41] Therefore the general restrictions regarding the Law of the secod week[42] and the quick raw flesh[43] are not applied to them.[44]

10. Anything that was part of a general principle and was later singled out to discuss another point not similar to [the general principle] was singled out in order to be more lenient as well as to be more stingent.

The particular implied in the general and excepted from it on account of some other special regulation which does not correspond in concept to the general, is thus isolated either to decrease or to increase the rigidity of its application.

The Torah[45] states a general rule that a Jewish servant gains his freedom after six years of servitude. Later (v.7) the Torah singles out a Jewish female servant and rules that she does not go free as does a Jewish servant. On the one hand, this gives the Jewish female servant a lenient rule, that unlike a male servant, she gains her freedom upon reaching adulthood (around the age of 12) or upon the death of the master. On the other hand, it gives her also a stringent rule, for her master may marry her if he so desires.[46]

According to Shemot 21:29-30, the proprietor of a vicious animal which has killed a man or a woman must pay such compensation as may be imposed on him by the court. In a succeeeding verse, the Torah adds: “If an ox goes a slave, male or female, he must pay the master thirty shekels of silver”. The case of a slave, though already included in pre preceding general law of the slain man or woman, contains a different provision, the fixed amount of compensation, with the result that whether the slave was valued at more than thirty shekels or less than thirty shekels, the proprietor of the animal must invariably pay thirty shekels.

The details on laws of plagues in the hair or beard[47] are dissimilar from those in the general rule of plague spots. Therefore both the relaxation regarding the white hair mentioned in the general rule[48] and the restriction of the yellow hair mentioned in the particular instance[49] are applied[50].

11. Anything that was part of a general principle and was singled out to be considered in a new matter, you cannot return it to its general principle unless Scripture returns it explicitly to its general principle.

The particular implied in the general and excepted from it on account of a new and reversed decision can be referred to the general only in case the passage under consideration makes an explicit reference to it.

The Torah[51] permits anyone owned by, or born to a kohen (Priest), and his immediate family to eat terumah (fruits or grains designated for a kohen). Hence a kohen’s daughter may eat terumah. However, should she marry a non-kohen, she would be prohibited from eating terumah. (The Torah removed her from the general principle.) Should her husband then die or divorce her, she would be permitted to resume eating terumah (if she has no children from him) only because the Torah returned her to the category the daughter of a kohen, and explicitly permitted her to do so.

The guilt-offering which a cured leper had to bring was unlike all other guilt-offerings in this, that some of its blood was sprinkled on the person who offered it.[52] On account of this peculiarity none of the rules connected with other offerings would apply to that brought by a cured leper, had not the Torah expressly added: “As the sin-offering so is the guilt-offering”.

The guilt offering of the leper requires the placing of the blood on the ear, thumb, and toe.[53] Consequently, the laws of the general guilt offering, such as the sprinkling of the blood on the alter[54] would not have applied, were it not for the Torah passage: "For as the sin offering is the priest's so is the guilt offereing",[55] i.e. that this is like other guilt offerings.[56]

12. A matter derived from its context, or a matter derived from its end (i.e. from what follows it).

Deduction from the context.

The Torah included You shall not steal as one of the ten commandments. It is not clear, however, whether this verse is a prohibition against stealing property or against stealing a human being, i.e. kidnapping. The Sages derived from the context that it is a prohibition against kidnapping, which is a capital offense, since the preceding, and following, injunctions, You shall not murder and you shall not commit adultery are capital offenses.

The Torah first writes[57] no person shal have relations with any relative. This verse implies that it is forbidden to marry any relative, regardless of how distant. The Torah then proceeds to list which relatives are forbidden in marriage, indicating that one may marry any relatives that are not included in that list, namely, the more distant relatives.

The noun tinshemeth occurs in Vayikra (Leviticus) 11:18 among the unclean birds, and again (verse 30) among the reptiles. Hence, it becomes certain that tinshemeth is the name of a certain bird as well as of a certain reptile.

In Devarim 19:6, with regard to the cities of refuge where the manslayer is to flee, we read: “So that the avenger of blood may not pursue the manslayer … and slay him, and he is not deserving of death”. That the last clause refers to the slayer, and not to the blood avenger, is made clear by the subsequent clause: “inasmuch as he hated him not in time past”.

"I put the plague of leporasy in a house of the land of your possesion",[58] refers only to a house built with stones, timber, and mortar, since these materials are mentioned later in verse 45.

13. The resolution of two verses that [seem] to contradict one another is that a third verse will come and reconcile them.

When two Biblical passages contradict each other the contradiction in question must be solved by reference to a third passage.

The Torah writes[59] In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth (see Rashi for the explanation of this verse). This verse implies that the heavens were created before the earth. But later it writes[60] on the day that God made earth and heavens, which implies that the earth was created first. However, a third verse resolves the apparent contradiction by stating[61] (HaShem says:) Also my Hand founded the earth while my right hand formed the heavens, indicating that the heavens and earth were created simultaneously.

In Shemot 13:6 we read: “Seven days you shall eat unleavened bread”, and in Devarim 16:8 we are told: “Six days you shall eat unleavened bread”. The contradiction between these two passages is explained by a reference to a third passage[62] where the use of the new produce is forbidden until the second day of Passover. Hence, the passage in Shemot 13:6 must refer to unleavened bread prepared of the produce of a previous year.

After being commanded to remove Isaac from the altar, Avraham asked HaShem to explain two contradictory verses. First HaShem said that Isaac would be the forefather of Israel[63] and then He commanded that Avraham to slaughter him[64] HaShem explained that the wording of the command was to place Isaac on the altar, but not to slaughter him on it.[65] Thus, there is no contradiction.

Rashi’s Commentary for: Bamidbar (Numbers) 7:89 When Moses would enter [When there are] two contradictory verses, the third one comes and reconciles them. One verse says, “the Lord spoke to him from the Tent of Meeting”,[66] and that implies outside the curtain, whereas another verse says, “and speak to you from above the ark cover”[67] [which is beyond the curtain]. This [verse] comes and reconciles them: Moses came into the Tent of Meeting, and there he would hear the voice [of God] coming from [between the cherubim,] above the ark cover.[68]

Rules seven to eleven are formed by a subdivision of the fifth rule of Hillel; rule twelve corresponds to the seventh rule of Hillel, but is amplified in certain particulars; rule thirteen does not occur in Hillel, while, on the other hand, the sixth rule of Hillel is omitted by Ishmael.

* * *

The Bnei Yisaschar[69] explains that the thirteen middot of Rabbi Yishmael used to explain the Torah correspond to the 13 middot harachamim which we invoke when we recite selichot. Yet, these thirteen are not a single unit, but actually are divided into a group of twelve middot of chessed and one middah of din. The single middah of din, which is described by the name “K-l”, corresponds to the middah of kal v’chomer. The Talmud, in fact, uses the simple term “din” as a reference to kal v’chomer, e.g. the mishna in Bava Kamma uses the expression “dayo l’ba min HaDin”. Halachically, there is a fundamental difference that exists between kal v’chomer and all the other middot used to explain the Torah. Only kal v’chomer can be derived purely on the basis of sevara, logical inference, while all the other middot require a tradition handed down from one’s teacher. The greatest chessed in the world is HaShem giving of himself to us. The middot of rachamim cause HaShem to reveal more of his presence in the world, and correspondingly, the middot we use to explain the Torah reveal how much more of HaShem’s presence is with us that we see through a superficial reading of the Torah. Yet, even at a time of din when HaShem’s presence is hidden, we must trust that he is with us and seek him out; even when there is no mesorah and tradition to explain a text of Torah, we are free to use kal v’chomer to seek and find that meaning ourselves. ‘Piha pascha b’chachma’, explains the Bnei Yisaschar, refers to the middah of kal v’chomer which requires human intellect to reveal; ‘v’Torat chessed al leshona’ refers to the laws explicitly stated in the Torah which fall under the rubric of chessed.

Sod - The 42 Rules of the Zohar for Sod Interpretation[70]

Here are 42 hermeneutical principles that will guide us in our efforts to experience Torah at the level of “voice”:

1. Literal Interpretation (Peshat): "The Torah speaks in the language of man" (Zohar I, 53a).

2. Allusion (Remez): "There is not a single word in the Torah that does not contain a hint to something else" (Zohar III, 152a).

3. Homiletical Interpretation (Derash): "The Torah has a body, which is the commandments, and a soul, which is the secrets" (Zohar II, 99a).

4. Mystical Interpretation (Sod): "Woe to the man who says that the Torah came to relate commonplace things and secular narratives" (Zohar III, 152a)

5. Gematria (Numerology): "The letters of the Torah are the garments of the Holy One, blessed be He" (Zohar II, 60a).

6. Notarikon (Acronyms): "Every word spoken by the Holy One, blessed be He, divides into several words" (Zohar II, 90b).

7. Atbash (Letter Substitution): "The Torah was given in the language of Atbash" (Zohar I, 24b).

8. Tzeruf (Letter Permutations): "The combinations of letters create worlds" (Sefer Yetzirah 2:2).

9. Symbolism of Names: "The names in the Torah are the secrets of the Holy One, blessed be He" (Zohar I, 4b).

10. Anthropomorphism: "The Torah speaks in the language of man" (Zohar I, 53a).

11. Dual Meanings: "Every verse in the Torah has seventy faces" (Zohar II, 99b).

12. Contextual Associations: "One verse is explained by another" (Zohar II, 108a).

13. Secrets of Creation (Ma’aseh Bereshit): "The account of creation is the root of all secrets" (Zohar I, 15a).

14. Secrets of the Chariot (Ma’aseh Merkavah): "The vision of Ezekiel is the key to the mysteries" (Zohar II, 82a).

15. Light and Darkness: "Light and darkness are two halves of a whole" (Zohar III, 47a).

16. Tikkunim (Rectifications): "The Torah is the remedy for all ailments" (Zohar II, 60b).

17. Exile and Redemption: "The Torah begins with kindness and ends with kindness" (Zohar I, 1b).

18. Yichudim (Unifications): "The purpose of the commandments is to unite the Holy One, blessed be He, with His Shechinah" (Zohar II, 81b).

19. Language of Secrets: "The Torah speaks in hints and allegories" (Zohar III, 152a).

20. Integration of Halacha and Aggadah: "The body of the Torah is the law, and the soul is the narrative" (Zohar II, 99a).

21. Midrashic Expansion: "The words of the Torah are poor in one place and rich in another" (Zohar III, 152a).

22. Sod (Mystical Secrets): "The Torah has a body and a soul; the body is the commandments, and the soul is the secret" (Zohar II, 99a).

23. Divine Names: "The entire Torah is the Name of the Holy One, blessed be He" (Zohar II, 60a).

24. Temporal Cycles: "The festivals of the Torah correspond to the cycles of the soul" (Zohar III, 255a).

25. Symbolism of Numbers: "The numbers in the Torah are the secrets of creation" (Zohar II, 4b).

26. Inner and Outer Realities: "The Torah has an inner and an outer aspect" (Zohar II, 60a).

27. Ascent and Descent: "The stories of the Torah are the descent for the purpose of ascent" (Zohar I, 86b).

28. Microcosm and Macrocosm: "Man is a small world, and the world is a great man" (Zohar II, 70b).

29. Tree of Life and Tree of Knowledge: "The Torah is the Tree of Life, and its secrets are the Tree of Knowledge" (Zohar I, 25b).

30. Speech and Silence: "There is a time to speak and a time to be silent" (Zohar II, 45b).

31. Heavenly and Earthly Mirrors: "The earthly Temple is a reflection of the heavenly Temple" (Zohar II, 231a).

32. Gender Dynamics: "The male and female were created as one" (Zohar I, 55b).

33. Worlds and Souls: "The soul descends through all worlds" (Zohar II, 99b).

34. Ladder of Ascent: "The Torah is a ladder upon which man ascends to God" (Zohar I, 149a);

35. Cycles of Existence: "All is in cycles, and the soul returns" (Zohar II, 99b);

36. Mystical Geography: "The journeys of Israel are the journeys of the soul" (Zohar III, 168a);

37. Hidden Letters: "The letters that are not written are the secrets of the Torah" (Zohar II, 90b).

38. Dualities: "Everything (except God) has its opposite" (Zohar)

39. Breaking of the Vessels (Shevirat HaKelim): "The Torah begins with chaos (Tohu), as it hints to the breaking of the vessels, for only through this can rectification (Tikkun) come" (Zohar II, 137a).

40. Shekhinah in Exile: "When Israel sins, the Shekhinah descends into exile with them, as hinted in the stories of the Torah" (Zohar I, 119a).

41. Mashiach and Redemption: "The secrets of the Torah all lead to the revelation of the Mashiach, who is hidden in the words of the Torah" (Zohar I, 25b).

42. Union of Torah Levels: "The Torah has four levels: Peshat, Remez, Derash, and Sod, and they are all one, united as the Holy Name is one" (Zohar II, 99b).

* * *

This study was written by

Rabbi Dr. Hillel ben David

(Greg Killian).

Comments may be submitted to:

Rabbi Dr. Greg Killian

12210 Luckey Summit

San Antonio, TX 78252

Internet address: gkilli@aol.com

Web page: http://www.betemunah.org/

(360) 918-2905

Return to The WATCHMAN home page

Send comments to Greg Killian at his email address: gkilli@aol.com