![]()

Corrections in Megillat Ruth

By Rabbi Dr. Hillel ben David (Greg Killian)

![]()

Tikkun is the Hebrew word for correction or repair. Thus if a person sins and damages the world, HaShem will send one of his descendants to correct the problem. Megillat Ruth, at one level, is all about corrections. The sin of Adam HaRishon must be corrected and ultimately the Mashiach will provide the tikkun as He sums up Israel into one new man. To understand how this works will require some understanding of the genealogy of the messianic line.

Terach had three sons: Avraham, Haran, and Nachor. Our Patriarchs Avraham, Yitzchak, and Yaaqov all married daughters of Haran. Ruth was also a grand-daughter of Haran. Thus we see that from Avraham and his descendants we have the male side of the messianic line that includes Lot, Judah, Elimelech, Machlon, and Boaz, and from Haran and his descendants we have the female side that included Lot’s daughters and Ruth. These are the patriarchs and matriarch, the mothers and fathers of the royal Messianic line.

From the male side we get the ideas that will shape the messianic line. From the female side we get the binah, the understanding as to how to apply these ideas from the male side. The spark of the male is fanned into the flame of reality by the female side.

In the evening meeting between Ruth and Boaz (chapter 3), the story alludes to two similar situations, Lot’s daughters (Genesis 19:31ff), and Tamar, Yehuda’s daughter-in-law (Genesis 38). The three situations have common features, most notably, that there are women who have little prospect of having further children who take actions to insure their own offspring. In both stories, a mitzva (a good deed) has the appearance of immorality. Additionally, each of the cases has the death of two husbands.

A Our Sages say that the acts of the daughters of Lot were intended to extract two good sparks, or portions. One is Ruth the Moabite and the other is Naamah the Ammonite.[1] Clearly these two sparks are related to the rectification of the two daughters of Lot who gave birth to the two peoples of Moab and Amon. They erroneously thought that the entire world had been destroyed, as in the time of the Flood, and that they had to retain the existence of the human race. Their good intention, which is the good spark within them, returned as the two converts, Ruth the Moabite and Naamah the Ammonite. Mashiach, whose role is to bring the earth to its final rectification, also descends from them.

It took ten years in Moab for the family to disappear. It took less than a year in Bethlehem for the ghostly remnants of the family to be rebuilt. A family of four, father, mother, and two sons, left Bethlehem, and a family of four was rebuilt in Bethlehem, Boaz, with Ruth and Naomi, acting as Obed’s mothers, and Ruth acting as Naomi’s daughter. Thus we have a father, a mother, a son, and a daughter.

The Tikkun of Yehudah and Tamar

Most folks see the encounter between Tamar and Yehudah as a sin of immorality. Torah, on the other hand, sees this encounter as a very great mitzva. It is a mitzva because Tamar was a childless widow, and her dead husband’s family was commanded[2] to raise up seed for the deceased. The family was required to raise up seed for the deceased on his land. When Yehudah failed to give his son, Shelah, to fulfill this mitzva, Tamar enticed Yehudah himself to fulfill it. The Midrash records[3] that HaShem sent an angel to “force” Yehudah, against his will, to turn in to Tamar’s tent. The angel asked Yehudah, “If you fail to turn to Tamar; from where will the Kings come?” So, Yehuda’s sin in not giving his son Shelah, the first in line for this mitzva, was corrected when Boaz gave way to Ploni Almoni, for the same mitzva, because he was first in line. This tikkun, this rectification, required enormous strength.

Yosef is the lost son who returns to his family, and the place from which he was dispossessed of his inheritance, Dotan Valley, is given later as an inheritance to his descendants, the daughters of Tzelofchad.

“Our father died in the desert... He died because of his own sin, and he had no sons.” [Num. 27:3]

There they resurrect their dead father’s name, and there they also resurrect the name of Yosef, who had been exiled by brothers.

In the case of Yehuda, Yoseph was made homeless and exiled from the land much as Elimelech and Lot, albeit involuntarily. Yoseph is the lost son who returns to his family, and the place from which he was dispossessed of his inheritance, Dothan Valley, is given later as an inheritance to his descendants, the daughters of Zelophehad. There they resurrect their dead father’s name, and there they also resurrect the name of Yoseph, who had been exiled by brothers.

The most prominent case of return to lost property appears in our Megillah, where the acquisition of Ruth overlaps with the purchase of the field of Machlon.

Ruth 4:5 When you acquire the property from Naomi and from Ruth the Moabite, you must also acquire the wife of the deceased so as to perpetuate the name of the deceased.

Redemption thus occurs when the name of the deceased is resurrected on his property. Parallel to this, in Parashat Behar we find the term redemption used with regard to the return of the freed slave to his property and the return of family estates in the Jubilee year.

When a slave, who sold himself to a foreigner and went out from amongst his nation, is returned to his property, that is called redemption. The prophet Yechezkel[4] describes the redemption of the nation of Israel in a similar manner. First, the nation will return to the land of its inheritance. Immediately afterwards, HaShem purifies Israel:

Yehezechel (Ezekiel) 36:25 I will sprinkle pure water on you and you will be pure.

Here, the parallel to the red heifer is clear (and therefore these verses are known to us from the Haftarah of Parashat Parah) - purification from the impurity caused by contact with the dead. After these verses comes the chapter on the dry bones, “I will cause breath to enter you and you shall live” (37:5). Thus, the redemption of the nation of Israel begins as the redemption of the land, and on the redeemed land the dry bones arise and live.

The land, the inheritance, gives man his connection to eternity. The days of the land are “like the days of the world” (as Rashi explains), and even though man’s days are limited, his connection to the land gives him eternal life. When a person is rooted in his property and passes it to his son and grandson, only then does he taste immortality. Cain’s punishment for the murder is that “You shall become a ceaseless wanderer on earth”.[5] In parallel, when the nation of Israel is punished with exile, when it is evicted from the land of the living, it turns temporarily into a “dead” nation until the redemption of the bones, the resurrection of the dead on his property. The same rooting in the land is described by the verse:

Yeshayahu (Isaiah) 65:22 For the days of My people shall be as long as the days of a tree.

The tree embodies eternal existence, as described in:

Iyov (Job) 14:7-9 There is hope for a tree; if it is cut down it will renew itself ... at the scent of water it will bud.

Even after the tree has dried out, it can still revive itself through its attachment to the land. But the death of man, who is not attached to the land, is an eternal death.

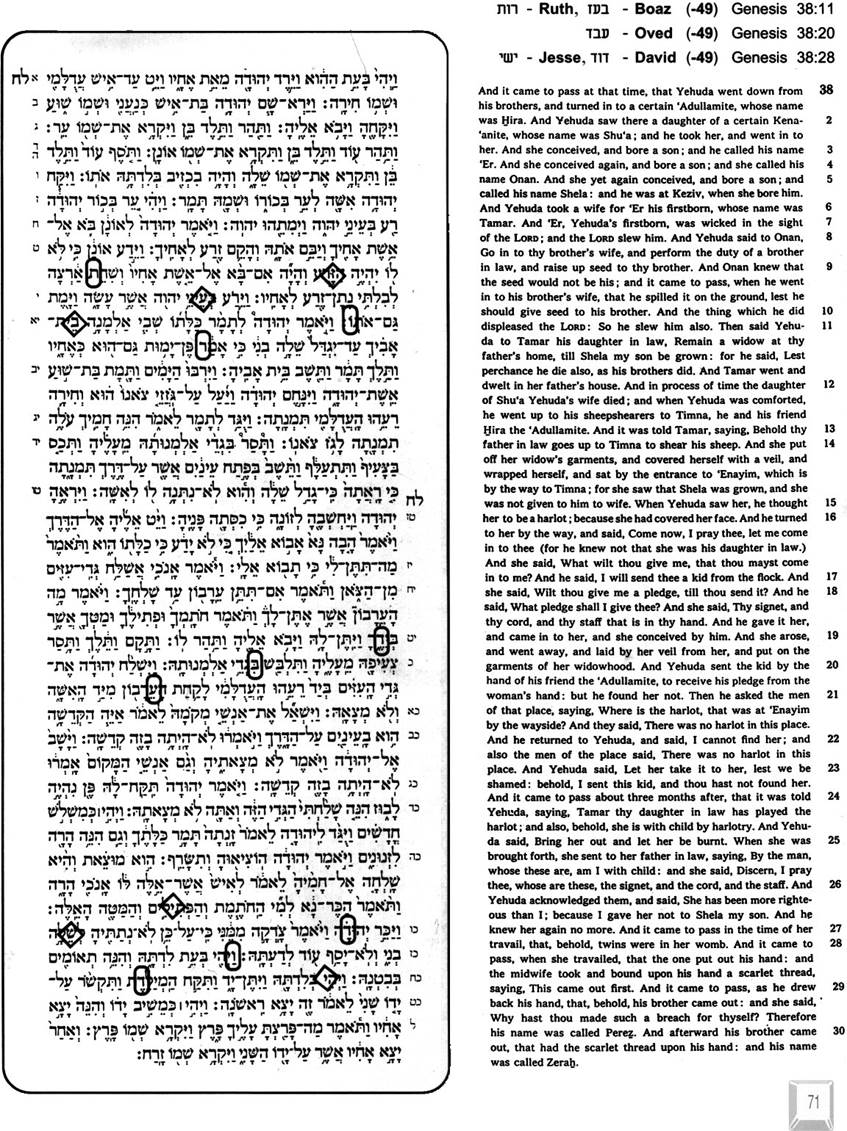

Dr. Moshe Katz (CompuTorah) found an interesting connection between the story of Yehuda and Tamar in a Bible code. The passage about Judah and Tamar, in Bereshit (Genesis) 38, is linked with sefer Ruth in a Bible code. Using a forty-nine letter code (the number we count for Sefirat HaOmer), we discover the central figures in Sefer Ruth: Ruth, Boaz, Oved, Yishai, and David. Ruth and Boaz are found together in Bereshit 38:11 at a minus forty-nine letter skip interval. Oved, their son is found in Bereshit 38:20, also at a minus forty-nine letter skip interval. Yishai and David, their grandson and great-grandson, are found in Bereshit 38:28, at a minus forty-nine letter skip interval. A copy of this page can be found at the end of this paper.

The Tikkun of Lot and His Eldest Daughter

Many folks see the encounter between Lot and his eldest daughter [From the younger descended Naamah the mother of Rehoboam[6] the first King of Judah.] as incest. The Torah, however, records this encounter as a GREAT mitzva (good deed). The eldest daughter truly believed that the only way to fulfill the mitzva of filling the earth, was through her father. So, as repulsive as the act was, she endured it in order to sanctify the name of HaShem. So great was the effort that she was rewarded with offspring (Ruth) to become a part of the Messianic line.

When the sun came up on the day HaShem was to destroy Sodom, the angels told Lot, “Get up and take your wife and your two daughters who are found.” Why did the Torah write, “who are found”? The verse would be easy to understand without writing the phrase, “who are found”!

Rabbi Yitzchak[7] says that this word is connected with the verse in:

Tehilim (Psalms 89:21 I have found David my servant

This refers to Mashiach. And where did HaShem find Mashiach? In Sodom!

But how does Mashiach come from Sodom? Because from one of Lot’s daughters came Ruth, from whom came King David, from whom comes Mashiach. In fact, the reason Lot’s daughters were saved was for the sake of King David and Mashiach.

The sin of Lot’s eldest daughter was not incest. Her sin was in not consulting Lot so that He could bring his wisdom to bear on this situation. This sin had its tikkun, its rectification, on the threshing floor, when Ruth deferred to Boaz to tell her what to do. She did this even though it resulted in great disappointment and a potential loss of Boaz.

There is another connection to this tikkun: Just as Lot abandoned the land of Israel and went away from Avraham, so too did Elimelech. Lot left Avraham’s house for a land that became known as part of Moab. Lot’s departure constituted not only a geographic exit from Israel but also a cultural and religious exit, from the Godly nation of Avraham to a foreign nation, from Avraham’s way of life (which followed the path of God, a way of charity and justice) to its opposite, the Sodomite way. According to Chazal (The Sages), Lot declared: “I do not want Avraham and his God.”

Elimelech repeats the same act[8], and there is no doubt that it has the same significance; as Chazal say, “One who lives outside of Israel is like one who has no God”. Elimelech’s sons marry non-Jewish women.[9] He becomes immersed in foreign culture, and, essentially, he leaves Avraham and his God, attaching himself to the culture of Moab. For this reason, his punishment is also so great.

Lot in his time was punished in a similar manner - his wife dies, his sons-in-law and married daughters are destroyed, and he remains an old man with daughters who cannot marry. Elimelech, too, leaves behind a wife who cannot bear children, and two daughters-in-law whom no man in Israel will come forward to redeem.

In Megillat Ruth there is a meeting between the House of Yehuda and the family of Lot. We find a similar sin with a similar punishment with regard to Yehuda. Although Yehuda did not leave the country and did not abandon his father’s culture, he did force this fate onto his brother Yosef, causing him to leave his father’s home and culture with the intent that he should become defiled by the culture of a foreign nation. The punishment exacted of Yehuda is similar to that which befalls both Lot and Elimelech. Immediately after selling Yosef, Yehuda marries; his wife later dies, his two sons die, and in his opinion, his third son cannot perform the act of yibum (levirate marriage) with his daughter-in-law. He is left without any assured continuity.

The tie that binds these cases is that in all three stories there is almost a total loss of family, but at the last minute a solution is found through the act of yibum. With regard to Yehuda, the yibum is mentioned expressly in the text. With regard to Lot, the matter is hinted at. Professor Benno Jacob points out a linguistic anomaly in the statement of Lot’s daughters: “And there is not a man on earth to consort with us”[10]. In Hebrew, the word “Aleinu” is unusual; usually the word “eleinu” would be used in this context. The only other time that “Aleinu” appears in a similar context is in the chapter on yibum: “Her husband’s brother shall unite with her”[11]. In other words, this hints that yibum was at the heart of Lot’s daughters’ attempts to revive their father’s seed and rebuild the name of the family that perished.

In the third case, that of Boaz and Ruth, there is no expression relating to yibum, but the text does state, “So as to perpetuate the name of the deceased on his estate”[12], similar to what is written in the parsha on yibum, “... shall be accounted to his dead brother, that his name not be blotted out in Israel“[13]. Yibum in all three cases is the solution to the problem, but in all three cases, the yibum is irregular. We do not find here a standard case of yibum between the brother of the deceased and the widow; rather, we have a father (Lot) with his daughter, a father (Yehuda) with his daughter-in-law, and the father’s brother (Boaz) with the father’s daughter-in-law. These irregular, surprising acts of yibum are what return the families to the land of the living.[14]

With Ruth, a beautiful tapestry of tikkun, intricately woven across the centuries, is revealed for all to see. Ruth “returns” to Eretz Yisrael and she “returns” to the God of Avraham. She takes the disparate threads of her ancestors and displays them as the tapestry of majesty! she rectifies the sin of Lot, in a spectacular way, and carried Machlon back to the land to rectify the sin of Elimelech. In Ruth and Boaz, the Kingly qualities of both Avraham and Yehudah are reunited in a spectacular display of intricacy that only HaShem could have done. Rightly has the story of Ruth been called “A Harvest of Majesty”!

But wait! There is much more to this tikkun! Rabbi Moshe Alshich suggests that Ruth is a gilgul[15] of Lot’s eldest daughter. When we compare Ruth and Lot’s eldest daughter, we see that they share many common points.

Man’s existence depends on passing his property to his sons or to those who come in their place due to yibum. We have mentioned three stories: the first (Lot) is the story of the birth of Moab. The second is the story of the birth of the House of Yehuda. The third is the story of the meeting between the two, between Ruth (Moab) and Boaz (Yehuda). The theme uniting the three is the resurrection of the name of the dead on his property. This is redemption, and this is the goal of the House of David, to reestablish the People of Israel on its land. When all hope is gone, there is still the possibility of yibum, even in an irregular, unnatural manner, which allows the name of the deceased to be resurrected on his property. When this “irregular tapestry is turned over, we can see that all of those odd threads have been perfectly placed by HaShem. They have been perfectly woven into the tapestry of our redemption.

As we begin comparing the events of Megillat Ruth with the story of Lot and His daughter, along with the story of Yehuda and Tamar, we will begin to see how the protagonists of Megillat Ruth will effect a tikkun, a rectification of the sins of their ancestors. In Sefer Ruth, there is an emphasis on Ruth’s modesty and Boaz’s self-control. Ruth, unlike Lot’s daughters, makes only a symbolic advance to Boaz, who had been drinking of his own accord. Lot’s daughters, on the other hand, get their father drunk and have relations with him. Boaz’s self-control, in contrast to Yehuda’s impulsive behavior, allows him to follow the proper procedure regarding the more rightful redeemer. Rabbi Sassoon explained that the meeting between Ruth and Boaz is a tikkun, rectification, of the previous two encounters. Ruth is the descendant of the product of the first encounter (Lot and his eldest daughter), Moab, and Boaz is a descendant of a product of the second encounter (Judah and Tamar), Peretz. It is the correction of these earlier encounters that eventually leads to the birth of the ruling dynasty in Israel, and ultimately to the Mashiach.

Ruth the Moabite joins the tribe of Judah, through an act of kindness, and she becomes the great-grandmother of David ben Yishai, the king of Israel. Predictably, Sefer Shmuel summarizes his reign as follows:

2 Shmuel (Samuel) 8:15 “And David reigned over all of Israel, and David performed Torah law and Charity for his entire nation.”

Recall that David had earlier hidden out in a CAVE (not unlike the cave when Lot encountered his daughters) in the area of the Dead Sea (Ein Gedi), where he performed an act of kindness by not injuring Shaul.[16]

The Kingship of David constitutes the tikkun for the descendants of Lot. His kingdom was characterized by the performance of tzedaka (Charity) and mishpat (Torah law), the antithesis of Sodom, Moab, and Ammon.

One of the most important roles for Mashiach to fulfill, is this tikkun, this rectification:

II Luqas (Acts) 3:19-21 Repent, then, and turn to God, so that your sins may be wiped out, that times of refreshing may come from the Lord, And that he may send Mashiach, who has been appointed for you--even Yeshua. He must remain in heaven until the time comes for God to restore everything, as he promised long ago through his holy prophets.

This correction, this return to the faith and obedience of the Patriarchs is forcefully proclaimed in the closing verses of Malachi:

Malachi 4:4-6 “Remember the law of my servant Moses, the decrees and laws I gave him at Horeb for all Israel. “See, I will send you the prophet Elijah before that great and dreadful day of HaShem comes. He will turn the hearts of the fathers to their children, and the hearts of the children to their fathers; or else I will come and strike the land with a curse.”

The father, in this context, is one’s Torah teacher. The Son’s are the talmidim of the teacher. This return to the fathers is nothing less than a return to the Torah of Moses, as we can see from the context.

All of the basic soul-roots from Adam on, become gilgulim in order to continue to elevate their tikkun, their rectification.

Is it logical to expect that another gilgul of that soul will appear just before the coming of Mashiach?

Why did HaShem consistently look outside of the Jewish nation, when compiling the gene pool for our Savior? (See my study titled: FLOWER.)

What was Ruth doing in the field of Boaz? She was performing Leket, gathering ears of corn. She gleaned and picked up. Leket is a halachic and metaphysical institution, HaShem gleaned and gathered beautiful inclinations and virtues from people all over the world in order to weave the soul of the king Mashiach. HaShem was preoccupied with the Mashiach’s personality. He disregarded race and religion and instead looked through all of mankind to find special qualities and capabilities. This is the Almighty’s approach to culture, to sift and glean through the nations of the world noting outstanding moral traits and ethical accomplishments.

Ruth was chosen because of her unique heroism. She came from pagan royalty, a life intoxicated with orgiastic pleasures and unlimited luxury. Ruth sacrificed all this to identify with a strange and mysterious people, to adopt a religion that demanded superhuman discipline.

Why is Ruth, who was alone, being compared to Rachel and Leah “the TWO of whom together built the house of Israel”?[17] What did they mean by saying that Rachel and Leah were two and that they were together and how does this relate to the current situation? Why did they put it into the double context of Ephrath and Bethlehem?

I think that the intent is to call attention to Naomi, to the role that Naomi will play together with Ruth. Throughout this book we have encountered the symbiotic relationship between Ruth and Naomi. These two women function almost as one, distinct in bodies but united in outlook, values and spirit. It is as if Ruth is a proxy for Naomi for Naomi is not only a mentor but a partner in everything that Ruth does. Naomi is Ruth and Ruth is Naomi and the two share accomplishment and fulfillment. These two kindred spirits rectify the conflict and lack of harmony between the two sisters, Rachel and Leah that ultimately expressed itself in strife between the Kingdom of Israel, led by Ephraim who stemmed from Rachel, and the Kingdom of Judah, descendant from Leah. This lack of unity directly led to the long and bitter exile in which we still find ourselves. The Bach and Ben Ish Chai both suggest that Ephrath is mentioned as an allusion to Ephraim whereas Bethlehem is associated closely with the tribe of Judah. Davidic monarchy is then a reflection and a re-enactment of the birth of the nation. In this fashion the destiny of Ruth is tied not only to the past but also to the future, separation is transformed into harmony and redemption shines out upon the world.

Trembling – Yitzchak vs. Boaz

There is a question concerning another prominent woman in Tanach[18], Rivka, who orders Yaakov to seize deceptively the blessings intended for his brother. Convinced that Yaakov deserved the blessings, by virtue of both his character and the explicit prophecy she had received from God – “the older will serve the younger”,[19] Rivka instructs Yaakov to deceive his father and take his brother’s blessing. In both instances, the women felt assured of their scheme’s success, despite the considerable risk entailed. The Midrash[20] indeed draws a comparison between these two incidents:

Mishlei (Proverbs) 29:25 A man’s trembling becomes a trap for him.

This refers to the trembling Yaakov caused Yitzchak, as it says, ‘Yitzchak was seized with very violent trembling.’ He should have cursed him, only ‘But he who trusts in HaShem shall be safeguarded’ – You placed [an idea] in his heart to bless him, as it says, ‘Now he must remain blessed.’ [This verse also refers to] the trembling Ruth caused Boaz, as it says, ‘The man trembled and pulled back.’ He should have cursed her, only ‘But he who trusts in the Lord shall be safeguarded’ – You placed [an idea] in his heart that he would bless her, as it says, ‘You are blessed to the Lord, my daughter.’”

It is doubtful, however, whether this comparison between Naomi and Rivka could justify what Naomi did. The commentaries have noted that Yaakov’s deception was the direct cause of his exile, not only practically, but also on the level of reward and punishment. Many sources have also observed the clear parallel between Lavan’s duplicity towards Yaakov, particularly in substituting Rachel with Leah, and Yaakov’s seizing of Esav’s blessing. The Midrash comments:

Bereishit Rabba 70:19 “Throughout the night, he would call to her, ‘Rachel,’ and she would respond. In the morning, ‘Behold, she was Leah.’ He said: You are a trickster, the daughter of a trickster! She said to him: Is there a teacher without students? Did your father not similarly call to you, ‘Esav,’ and you responded? You, too, called to me and I responded.”

This Midrash clearly Yaakov’s experiences with Lavan as a punishment measure for measure for deceiving his father.[21]

In our context, too, the Midrash[22] emphasizes the chillul HaShem[23] that could have resulted from Ruth’s visit to the threshing floor:

“Rabbi Chonya and Rabbi Yirmiya said in the name of Rav Shemuel bar Rav Yitzchak: That entire night, Boaz was spread out on the floor crying, ‘Master of the worlds! It is revealed and known to You that I did not touch her. May it be Your will that it not be known that the woman came to the threshing floor, so that the Name of HaShem not be desecrated through me!’”

Torah Codes dealing with Sefer Ruth

An interesting example is shown in the picture below this text. The text which is Bereshit 38 tells the story of Yehuda and Tamar. As the result of their affair, Tamar gave birth to Perez and Zerach. From the book of Ruth we learn that Perez started a lineage which led to Boaz. Boaz married Ruth and had a son Oved, which had a son Yishai, which was the father of King David. So it was a natural question to ask whether King David with his lineage is hidden in this chapter. Indeed, you find the names Boaz, Ruth, Obed, Yishai, and David spelled out with the same interval minus forty-nine, moreover they all appear in the chronological order! We already mentioned the importance of forty-nine being the 7th Shmita followed by the Jubilee. However forty-nine is also the last day of the counting of Omer which starts on the second day of the Passover and ends a day before Shavuot. Every day in this counting has a name and the forty-nineth is called – “kingdom of the kingdom”. Is there a name which would fit David, the king of kings, better? Let us also mention that David was born and died on the very day of Shavuot and the book of Ruth is traditionally studied on this holiday. But maybe this system is another coincidence? It is easy to estimate the probability of such an event. As we count the total number of letters in Bereshit 38 and the relative proportion of each of the letters of alphabet, we come to the conclusion that the probability of the word Boaz to appear in our chapter with a given interval is 0.02. (That is assuming that on the level of equal intervals the text is random). Similarly, for the other four names the probabilities are 0.63,0.065,0.76 and 0.25. The odds for all five names to show up with a given interval are about 1 in 6,500. If we also request that the names line up in chronological order, the chances are reduced to 1 in 800,000. Now, if one would claim that the interval forty-nine is as important as minus forty-nine and the same for 50 and -50, these 3 possibilities would in- crease the chances to 1 in 200,000 - still quite an impressive number!

This study was written by

Rabbi Dr. Hillel ben David

(Greg Killian).

Comments may be submitted to:

Rabbi Dr. Greg Killian

12210 Luckey Summit

San Antonio, TX 78252

Internet address: gkilli@aol.com

Web page: http://www.betemunah.org/

(360) 918-2905

Return to The WATCHMAN home page

Send comments to Greg Killian at his email address: gkilli@aol.com

[1] Melachim alev (I Kings) 14:21

[2] Devarim (Deuteronomy) 25:5

[3] Midrash Rabbah - Genesis LXXXV:8

[4] Chapter 36

[5] Bereshit (Genesis) 4:12

[6] Melachim alev (I Kings) 14:21

[7] Bereshit Rabbah 41:4

[8] This section was adapted from Rav Yaakov Medan.

[9] According to Rashi and Chazal but not according to Ibn Ezra

[10] Bereshit 19:31

[11] Devarim 25:5

[12] Ruth 4:5

[13] Devarim 25:6

[14] The land of the living is Israel.

[15] A transmigrated soul. When Yeshua calls Yochanan (John) ‘The Elijah who was to come’, He was indicating that Yochanan had the soul of Elijah.

[16] See I Shmuel (I Samuel) 24:1-15; note especially 24:12-15. See also Yirmiyahu (Jeremiah) 22:1-5

[17] Ruth 4:11

[18] Tanach is an acronym for Torah, Neviim, and Ketuvim. These are the Hebrew words for Law, Prophets, and Writings. This is what Jews call the Old Testament.

[19] see Targum Onkelos and Rashbam to Bereishit 27:13

[20] Ruth Rabba 6:1

[21] For further elaboration on this subject, see Nechama Leibowitz’s “Studies on Sefer Bereishit.”

[22] Ruth Rabbah 7:1

[23] Desecration of God’s Name