![]()

By Rabbi Dr. Hillel ben David (Greg Killian)

![]()

I. Introduction[1]

In this study I would like to study the unusual letters found in the Tanach.

What is The Torah?

Torah literally means “instruction”. The Torah is THE central ‘teaching’ for Jews. The Torah consists of the ‘Five Books of Moshe’s:

|

ENGLISH |

|

|

Bereshit |

Genesis |

|

Shemot |

|

|

Vayikra |

Leviticus |

|

Bamidbar |

|

|

Devarim |

Deuteronomy |

A Torah scroll is a scroll that contains these five books of Moshe:

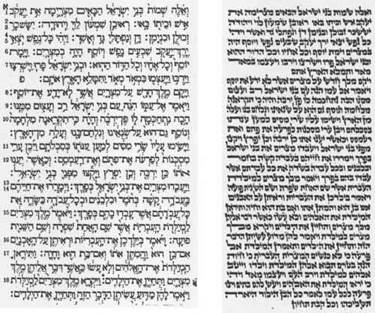

Sefardi Torah Scrolls

|

|

|

Ashkenaz Torah Scroll

The Torah scrolls found in the ark of the local Jewish synagogue are a powerfull testimony to the accuracy and integrity of The Word of HaShem, as delivered to Moshe ( Moshe).

Torah Ark

A Torah scroll is written on scored cow hide with special black ink and quill. Each page is then sewn to the previous page using gut from a kosher animal.

However, it is not the materials which are amazing, but the writing itself. This amazing text is easily the most accurate in the world. It is also contains an amazing amount of coded information beyond the text itself.

The Script By Rabbi Yitzchak Hutner[2]

The Sages teach in Sanhedrin 21b that, “Ezra the Scribe, had he lived then, would have been worthy of receiving the Torah. Instead, he was responsible for changing the Hebrew script." Concerning this the Maharal wrote[3] that, “this is something of exalted wisdom, that the Torah script was changed specifically by Ezra the Scribe.” This matter contains sublime Torah secrets.

We know that at the time of Ezra, the style of Hebrew script was changed from the “Ivri script” to the “Ashuri script”. Note: There are two types of Hebrew script, the ancient Ivri script found on ancient coins and writings, or the “Ashuri script” which has been used since the time of Ezra in Sifrei Torah and sacred texts, and has become the standard format for all Hebrew writing.

The Maharal writes[4] that changing the Hebrew script was not like a prohibition that was subsequently permitted, it is like eating meat for pleasure which was at first prohibited, but for a limited time only. A similar approach was taken regarding the Hebrew script. At the time of revelation, the Torah was written in the “Ivri script”, but they were immediately informed that this script would eventually be changed. The Maharal explains that the origin of Israel (i.e. Abraham) was on ‘the other side of the river’, which is the reason we are called Ivrim, Hebrews. So long as Israel was in the mode of being founded, it employed the “Ivri script”, however when they experienced exile for the first time, Israel lost its status of being in a ‘beginning state’. It was then that the script was changed (this is explained in greater detail in Maharal’s Sefer HaTiferet.)

This is the place where we can identify the relationship of shared destiny between Israel and the Torah even in their normal period of ingathering. So long as Israel lived on their land, the Holy Scriptures were continuously being written. The continued writing of the Holy Scriptures is referred to with the words, “that I wrote” {Shemos 24:12) as is explicitly stated in the Torah. This writing was in “Ivri script” which is associated with the “beginning mode”, the mode of Israel at that time. Here we find a shared destiny between Israel and its Torah in that the script of Torah writing at the time they first lived in Eretz Israel was written in the style and form of the time of Israel’s founding.

The Letters

A Torah scroll contains numerous letters which are non-standard in terms of size, placement, and orientation. These unusual characters are exactly the same from one Torah croll to the next. These are not mistakes, but rather, they contain vast amounts of information that is fereted out by our Sages and used to convey The Word of HaShem to His treasured people.

The letters of the Torah come in three sizes: large, small, and the standard letters with which most of the Torah is written. A large Alef is known as an Alef Rabbasi, a small Alef as an Alef Zeira. A medium-sized Alef is called an Alef Regila (a regular Alef).

There are about 100 abnormal letters in the Torah, as the Talmud teaches.

Men. 29b

Ber. 4a; Naz. 23a; Hot. 10b.

Meg. 16b

The Encyclopedia Judaica tells us that there are 17 places in the Torah where a letter is written extra-large or extra-small: the scribal terminology is majuscule and miniscule. There are six miniscules and eleven majuscules. For example, the first letter in the Torah, the beth in the word Bereshit, is a majuscule (this is probably the origin of the illuminated capital of medieval manuscripts). The most famous majuscules are certainly the ones from the Shema in Devarim (Deuteronomy) 6:4. In this case, the letters are large to avoid confusion: a large ayin in the word shema to avoid confusion with aleph: ‘perhaps O Israel.’ The large dalet to avoid confusion with resh: ‘the Lord is another’.

Scripts

Vellish, is the script generally used by Sephardi Jews.

Ari is the script generally used by Jews of Chassidic descent or influence.

Beit Yoseph is the script generally used by Ashkenazi Jews.

Quills and Ink

The scribe makes quills for writing a Sefer Torah. The feathers must come from a kosher bird, and the goose is the bird of choice for many scribes. The scribe carefully and patiently carves a point in the end of the feather and uses many quills in the course of writing one Sefer Torah. The scribe also prepares ink for writing the Sefer Torah by combining powdered gall nuts, copper sulfate crystals, gum arabic, and water, preparing only a small amount at a time, so that the ink will always be fresh. Fresh ink is a deep black, and only this is acceptable for writing a Sefer Torah.

Letters in the Torah

|

Letters |

|

Letters |

||

|

א |

27,057 |

|

ל |

21,570 |

|

ב |

16,344 |

|

מ |

25,078 |

|

ג |

2,109 |

|

נ |

14,107 |

|

ד |

7,032 |

|

ס |

1,833 |

|

ה |

28,052 |

|

ע |

11,244 |

|

ו |

30,509 |

|

פ |

4,805 |

|

ז |

2,198 |

|

צ |

4,052 |

|

ח |

7,187 |

|

ק |

4,694 |

|

ט |

1,802 |

|

ר |

18,109 |

|

י |

31,522 |

|

ש |

15,592 |

|

כ |

11,960 |

|

ת |

17,949 |

|

Total |

304,805 |

|||

Letters and Words in the Torah

|

|

Words |

Letters |

|

Bereshit (Genesis) |

20,512 |

78,064 |

|

Shemot (Exodus) |

16,723 |

63,529 |

|

Vayikra (Leviticus) |

11,950 |

44,790 |

|

Bamidbar (Numbers) |

16,368 |

63,530 |

|

Devarim (Deuteronomy) |

14,294 |

54,892 |

|

|

|

|

LARGE LETTERS

|

Passage. |

Hebrew Word. |

Translation. |

Hebrew Letter. |

|

Gen. 1:1 |

,hatrc |

beginning |

bet |

|

Gen. 30:42 |

;hygvcu |

feeble |

final pe |

|

Gen. 34:31 |

vbuzfv |

harlot |

zayin |

|

Gen. 50:23 |

ohaka |

final mem |

|

|

Ex. 2:2 |

cuy-hf |

good |

tet |

|

Ex. 34:7 |

rmb |

keeping |

nun |

|

Ex. 34:14 |

rjt |

other |

resh |

|

Lev. 11:30 |

|

lizard |

lamed |

|

Lev. 11:42 |

iujd-kg |

belly |

vav |

|

Lev. 13:33 |

|

shaven |

gimel |

|

Num. 13:31 |

|

stilled |

samek |

|

Num. 14:17 |

tb-ksdh |

be great |

yod |

|

Num. 24:5 |

|

how |

mem |

|

Num. 27:5 |

|

cause |

final nun |

|

Deut. 6:4 |

gna |

‘ayin |

|

|

Deut. 6:4 |

sjt |

dalet |

|

|

Deut. 18:13 |

|

perfect |

taw |

|

Deut. 29:28 |

ofkahu |

cast them |

lamed |

|

Deut. 32:4 |

|

tzade |

|

|

Deut. 32:6 |

vuvhk v |

Lord |

first he |

|

Josh. 14:11 |

|

strength |

first kaf |

|

Isa. 56:10 |

|

watchman |

tzade |

|

Mal. 3:22 |

|

remember |

zayin |

|

Ps. 77:8 |

|

forever |

he |

|

Ps 80:15 |

|

vineyard |

kaf |

|

Ps. 84:4 |

|

nest |

kof |

|

Prov 1:1 |

|

proverbs |

mem |

|

Job 9:34 |

|

het |

|

|

Song 1:1 |

|

song |

shin |

|

Ruth. 3:13 |

|

tarry |

nun |

|

Eccl. 7:1 |

|

good |

het |

|

Eccl. 7:13 |

|

conclusion |

samek |

|

Esth 1:6 |

|

white |

het |

|

Esth. 9:9 |

|

Vajezatha |

vav |

|

Esth. 9:29 |

|

wrote |

first taw |

|

Dan. 11:20 |

|

dawn |

second pe |

|

I Chron. 1:1 |

|

alef |

The large letters are used mainly to call attention to certain Talmudic and midrashic homilies and citations, or as guards against errors. References to them in Masseket Soferim is read substantially as follows:

The letters of the first word of Genesis, “Bereshit” (In the beginning), must be spaced (“stretched”; according to the Masorah, only the “bet” is large).

Bereshit (Genesis) 1:1 In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.

,tu ohnav ,t ohvkt trc ,hatrc

:.rtv

* * *

Bereshit (Genesis) 30:42 But when the cattle were feeble, he put [them] not in: so the feebler were Laban’s, and the stronger Jacob’s.

ohpygv vhvu ohah tk itmv ;hygvcu

:ceghk ohraevu ickk

* * *

Bereshit (Genesis) 34:31 And they said, Should he deal with our sister as with an harlot?

:ub,ujt-,t vagh vbuzfv rnthu

* * *

Bereshit (Genesis) 50:23 And Joseph saw Ephraim’s children of the third [generation]: the children also of Machir the son of Manasseh were brought up upon Joseph’s knees.

hbc od ohaka hbc ohrptk ;xuh trhu

:;xuh hfrc-kg uskh vabn-ic rhfn

* * *

Shemot (Exodus) 2:2 And the woman conceived, and bare a son: and when she saw him that he [was a] goodly [child], she hid him three months.

u,t tr,u ic sk,u vatv rv,u

:ohjrh vaka uvbpm,u tuv cuy-hf

* * *

Shemot (Exodus) 34:7 Keeping mercy for thousands, forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin, and that will by no means clear [the guilty]; visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children, and upon the children’s children, unto the third and to the fourth [generation].

vtyju gapu iug tab ohpktk sxj rmb

ohbc’kg ,uct iug q sep vebh tk vebu

:ohgcr-kgu ohaka-kg ohbc hbc-kgu

* * *

Shemot (Exodus) 34:14 For thou shalt worship no other god: for HaShem, whose name [is] Jealous, [is] a jealous God:

tbe vuvh hf rjt ktk vuj,a, tk hf

:tuv tbe kt una

* * *

Kiddushin 30a The early [scholars] were called Soferim[5] because they used to count all the letters of the Torah.[6] Thus, they said, the waw in gahon[7] marks half the letters of the Torah; darosh darash,[8] half the words; we-hithggalah,[9] half the verses. The boar out of the wood [mi-ya’ar] doth ravage it:[10] the ‘ayin of ya’ar marks half of the Psalms.[11] But he, being full of compassion, forgiveth their iniquity,[12] half of the verses.

Vayikra (Leviticus) 11:30 And the ferret, and the chameleon, and the lizard, and the snail, and the mole.

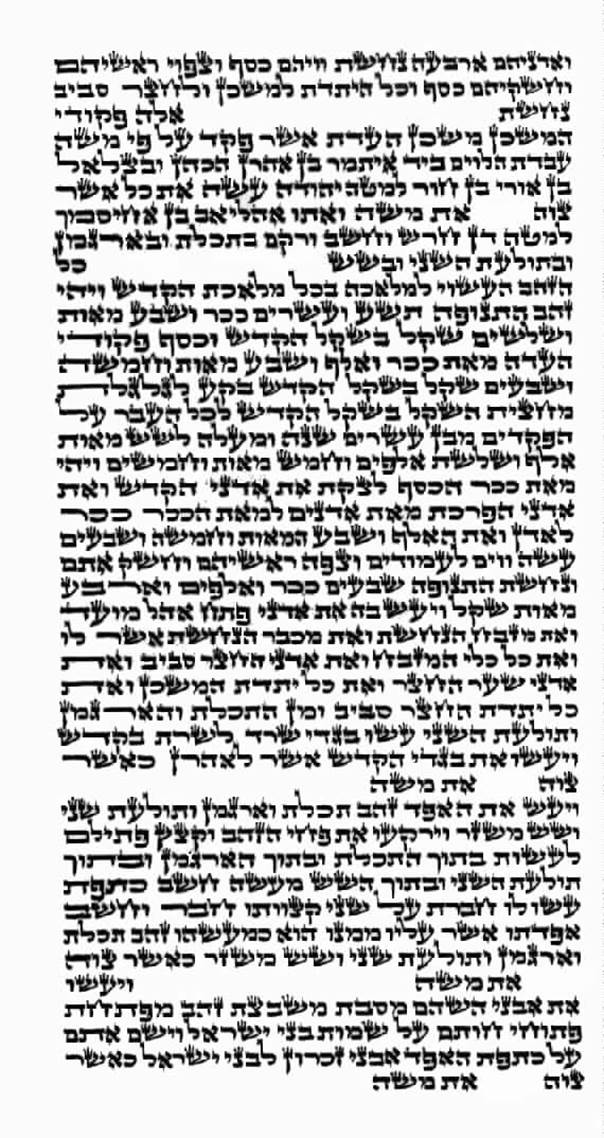

The u “vuv” in the word “gachon”, belly, must be raised because it is the middle central letter of the Torah. It is one of the eleven majuscules in the Torah.

Vayikra (Leviticus) 11:42 Whatsoever goeth upon the belly, and whatsoever goeth upon [all] four, or whatsoever hath more feet among all creeping things that creep upon the earth, them ye shall not eat; for they [are] an abomination.

gcrt-kgLlkuv q|kfu iujd-kgLlkuv kf

.rav .rav-kfk ohkdr vcrn-kf sg

:ov .ea-hf oukft, tk .rtv-kg

A Torah scroll contains 304,805 letters, which means that the midpoint would be the 152,403rd letter; but there are 157,236 letters until the letter vav in the word gachon. In order for that to be the middle letter of the Torah, there would have to be an additional 9,667 letters in the Torah scroll!

There is a fascinating explanation, by Rabbi Yitzchak Yosef Zilber, of this cryptic statement of the Talmud. While most of the letters of the Torah are written in the standard script, he says, there are certain letters that are different. Some are written in an unusual fashion, while others are bigger or smaller than the standard letters of the Torah. If one were to count all the small and large letters in a standard Torah scroll, one would find that there are 16 or 17 of these letters (depending on whether we count the truncated vav in Numbers 25:12.3) Of these, the ninth, i.e., the middle one, is the vav of gachon. In other words, the Talmud was not referring to the vav of gachon as the middle of all the letters of the Torah scroll; rather, it was referring to it as the middle of all the unusually large and small letters in the Torah scroll.[13]

The Psalms also have a corresponding middle letter:[14]

יְכַרְסְמֶנָּה חֲזִיר מִיָּעַר; וְזִיז שָׂדַי יִרְעֶנָּה יד

Tehillim (Psalms) 80:14 The boar out of the wood doth ravage it, that which moveth in the field feedeth on it.

* * *

The word “va-yishchat” (And he slew) must be spaced, as it is the beginning of the middle verse of the Torah (the Masorah designates the dividing verse as in Vayikra 8:8, but does not indicate that any change is to be introduced in the form or spacing of the letters).

Vayikra (Leviticus) 8:23 And he slew [it]; and Moshe took of the blood of it, and put [it] upon the tip of Aaron’s right ear, and upon the thumb of his right hand, and upon the great toe of his right foot.

i,hu unsn van jehu q|yjahu

ivc-kgu ,hbnhv irvt-iztLlub,’kg

:,hbnhv ukdr ivc-kgu ,hbnhv ush

* * *

Bamidbar (Numbers) 25:12 12 Wherefore say: Behold, I give unto him My covenant of peace;

יב לָכֵן, אֱמֹר: הִנְנִי נֹתֵן לוֹ אֶת-בְּרִיתִי, שָׁלוֹם.

The "small" vav in the word shalom, meaning "peace", in the verse, "Behold, I give to him my covenant of peace"[15] alludes to another verse: "…and the truth and the peace they loved".[16] The attribute which distinguishes Jacob is "emet/truth", whereas the attribute "habrit hashalom/the covenant of peace", is the one that distinguishes Joseph.

* * *

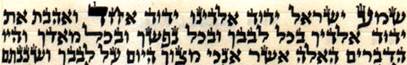

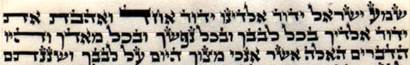

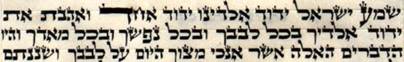

“Shema’” (hear; Shemot 6:4) must be placed at the beginning of the line, and all its letters must be spaced; “echad” (one), the last word of the same verse, must be placed at the end of the line (the Masorah has the “‘ayin” of “Shema’” and the “dalet” of “echad” large).

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 6:4 Hear, O Israel: HaShem is our God, HaShem is One:

:sjt q vuvh ubhvkt vuvh ktrah gna

The letters sg Ayin Dalet can be read “ade” which means “to bear witness.” In reading the “Shema” one is in effect testifying that God exists. Note that Ya’akov (Jacob) and Esau make a treaty of peace near a mound of stones called “gal-ade”, literally a mound (gal) of testimony (ade). (Genesis 31:46-48)

Alternatively, the letters sg Ayin Dalet can be read “ahd”, which means “until”. In other words, no matter one’s belief in HaShem, it can never be perfect, never absolutely absolute. One can come “until” the Lord, but never quite reach Him. Note the text describing repentance - “and you shall return until (ad) the Lord your HaShem,” (Devarim 30:2) as no one can ever return fully to HaShem.

Finally, the letter Ayin Dalet can be read ode, meaning “still.” This is perhaps to accentuate that against all odds, Jews throughout history in the darkest of times still declared belief in HaShem. Note the use of the word “ode” when Yosef reveals himself to his brothers when he asked, “ha’ode avi hai, is my father still alive?” (Bereshit 45:3) In amazement Yosef rhetorically was saying, ‘having endured so much, is father still alive?’

The “lamed” in the word “wa-yashlikem” (and he cast them) must be large (“long” = “‘aruk”).

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 29:28 And HaShem rooted them out of their land in anger, and in wrath, and in great indignation, and He cast them into another land, as [it is] this day.

vnjcu ;tc o,nst kgn vuvh oa,hu

,rjt .rt-kt ofkahu kusd ;mecu

:vzv ouhf

The letter v in vuvhk v (“HaShem”) must be spaced more than any other “he,” as “ha” is here a separate word (comp. Yer. Meg. 1.: “The ‘he’ must be below the shoulder of the ‘lamed’”; also Ex. R. 24: “The ‘he’ is written below the ‘lamed.’” The Masorah has a large “he” as indicating the beginning of a separate word).

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 32:6 Do ye thus requite HaShem, O foolish people and unwise? [is] not he thy father [that] hath bought thee? hath he not made thee, and established thee?

ofj tku kcb og ,tz-uknd, vuvhk v

:lbbfhuŠlag tuv lbe lhct tuv-tukv

Ruth 3:13 Tarry this night, and it shall be in the morning, that if he will perform unto thee the part of a kinsman, well; let him do the kinsman’s part; but if he be not willing to do the part of a kinsman to thee, then will I do the part of a kinsman to thee, as HaShem liveth; lie down until the morning.’

This righteous man’s words, הַלַּיְלָה ליני, “stay this night,” signify that only this night would Ruth stay alone, without a husband; the next morning she would be redeemed. Similarly, many generations later, the children of Israel would endure the night of exile, when they would be like a woman separated from her husband, with whom she will be reunited in the morning of her redemption. This is hinted at by rrt, which is composed of the end letters of the “four exiles”; Babylon (בב״ל), Media (מד״י), Greece (יו״ן), and Rome (רומ״י).

In this regard the letter nun (נ, numerically equivalent to 50), portends that the future exile would begin in the fiftieth generation, at the time of Nebuchadnezzar. Alternatively, the enlarged letter nun in certain texts alludes to the Messiah (a scion of Ruth), one of whose names was Yenon, ינון. [Thus it says, “Yenon is his name” (Psalms 72:17).][17]

SMALL LETTERS

|

Passage. |

Hebrew Word. |

Translation. |

Hebrew Letter. |

|

Gen. 2: 4 |

בְּהִבָּרְאָם |

he |

|

|

Gen 32:2 |

v,fcku |

kaf |

|

|

Gen. 27:46 |

|

weary |

kof |

|

Ex. 32: 25 |

|

enemies |

kof |

|

Lev. 1:1 |

trehu |

call |

alef |

|

Lev. 6:2 |

|

burning |

mem |

|

Num. 25:11 |

|

Phinehas |

yed |

|

Deut. 9:24 |

|

rebelious |

first mem |

|

Deut. 32:18 |

ha, |

unmindful |

yod |

|

II Sam. 21:19 |

|

Jaare |

resh |

|

II Kings 17:31 |

|

Nibhaz |

zayin |

|

Isa. 44:14 |

|

ash (tree) |

final nun |

|

Jer. 14:2 |

|

Tzade |

|

|

Jer. 39:13 |

|

Nebushazhan |

final nun |

|

Nah 1:3 |

|

Whirlwind |

samek |

|

Ps. 24:5 |

|

vain |

vav |

|

Prov. 16:28 |

|

whisperer |

final nun |

|

Prov. 28:17 |

|

man |

dalet |

|

Prov. 30:15 |

|

give |

bet |

|

Job. 7:5 |

|

clods |

gimel |

|

Job. 16:14 |

|

breach |

final tzade |

|

Lam. 1:12 |

|

nothing |

lamed |

|

Lam 2:9 |

|

sunk |

tet |

|

Lam. 3:35 |

|

subvert |

ayin |

|

Esth 9:7 |

|

Parshandatha |

taw |

|

Esth. 9:7 |

|

Parmashta |

shin |

|

Esth 9:9 |

|

Vajezatha |

zayin |

|

Dan. 6:20 |

|

very early |

first pe |

The name Abraham is alluded to already in the Genesis account of creation. Genesis includes two accounts of creation. The first runs from chapter 1 verse 1 to chapter 2 verse 3 and the second begins with chapter 2 verse 4.

Bereshit (Genesis) 2:4 These are the generations of the heaven and of the earth when they were created (בהבראם), in the day that HaShem God made earth and heaven.

However, sometimes chapter 2 verse 4 is considered the final verse of the first account of creation. This verse reads: “These are the chronicles of the heavens and the earth when they were created, on the day that God made earth and heavens.” In the original Hebrew, the words “when they were created,” are a single word: בהבראם . This is a very special word because it is the first time that a typographically minor letter appears in the text of the Torah: the second letter of this word, the hei (ה ) is this letter. Thus, in the Torah scroll this word is written something like this: בהבראם . But, this word is also special because when permuted it spells באברהם , which means “with Abraham.” The sages learn from this that all of creation was created in the merit of Abraham.

The h of the word ha,, teshi, (thou art unmindful; Devarim 32:18) must be smaller than any other “yod “ in the Scriptures.

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 32:18 Of the Rock [that] begat thee thou art unmindful, and hast forgotten God that formed thee.

lkkjn kt jfa,u ha, lskh rum jh

The h of ksdh, yigdal, (be great) must be larger than any other “yod” in the Torah (Yal., Num. 743, 945).

Bamidbar (Numbers) 14:17 And now, I beseech thee, let the power of HaShem be great, according as thou hast spoken, saying,

,rcs ratf hbst jf tb-ksdh v,gu

:rntk

The last word in the Torah, “Israel,” must be spaced and the “lamed” made higher than in any other place where this letter occurs (the Masorah has no changes).

* * *

“And it was, the life of Sarah, 127 years, the years of the life of Sarah”. The end of the next verse says that Avraham Aveinu came to eulogize Sarah Imeinu, v’livkosah- and cry over losing her. V’livkosah is inscribed with a small letter kaf. The commentary Ba’al Haturim says the little letter is telling us Avraham cried only a little because Sarah was an elderly woman.

Hakham Shimshon Rafael Hirsch says that the word šv,fcku, and to bewail her, is written with a small f to suggest that although Avraham’s grief was infinite, the full measure of his pain was concealed in his heart and the privacy of his home.

Bereshit (Genesis) 23:1-2 And Sarah was an hundred and seven and twenty years old: [these were] the years of the life of Sarah. And Sarah died in Kirjath-arba; the same [is] Hebron in the land of Canaan: and Abraham came to mourn for Sarah, and to weep for her.

iurcj tuv gcrt ,hrec vra ,n,u c

vrak spxk ovrct tchu igbf .rtc

:v,fcku

* * *

The word “vayikar” (“Vayikra” without an “Alef”) means “casually calling.” The word “Vayikra” (“Vayikra” with a “Alef”) means “to call with love.”

Vayikra (Leviticus) 1:1 And HaShem called unto Moshe, and spake unto him out of the tabernacle of the congregation, saying,

uhkt vuvh rcshu van-kt trehu t

:rntk sgun kvtn

Look at the opening word of the Book of Leviticus and you will see that the final letter of this word is written smaller than all the rest. The word is Vayikrah, “and He called”. The letter in question is the Aleph, the first letter of the Hebrew aleph-bet and kabbalistic symbol for the Ineffable God.

In the verse ‘VaYikra el Moshe,’ the Alef is small, alluding to Moshe Rabbeinu’s humility. Although Moshe was well aware of his extraordinary talents and abilities, he did not take pride in them or consider himself great. It states in the Torah, ‘And the man Moshe was very humble.’ According to Moshe’s way of thinking, had someone else been blessed with the same abilities, he would have certainly utilized them better.”

The Book of Leviticus opens with the verse “And the Lord summoned Moshe,” the first word being the Hebrew “Vayikra,” which means, “and He summoned or “called out to;” it is fascinating that a small “aleph” is the masoretic, traditional way of writing the Hebrew VYKRA, so that the text actually states “Vayiker, and He chanced upon, “ as if by accident. Rashi comments: “The word VaYiKRA precedes all (Divine) commandments and statements, which is a term of endearment used by the heavenly angels...; however, HaShem appeared to the prophets of the idolatrous nations of the world with a temporary and impure expression, as it is written ‘And He chanced upon (Va Yiker) Balaam’”. Apparently, when Moshe was writing the Torah dictated by HaShem, he was too humble to accept for himself the more exalted and even angelic Divine charge of VaYiKRA; therefore, he wrote the less complimentary VaYiker relating to himself, retaining his faithfulness to HaShem’s actual word VaYiKRA (“And He Summoned”) by appending a small aleph to the word VaYiKR.

The midrash goes one step further. It poignantly, if albeit naively, pictures the heavenly scene of Moshe, having completed his writing of the Five Books, being left with a small portion of unused Divine ink; after all, the Almighty had dictated VaYiKRA and Moshe had only written VyiKR A, rendering the ink which should have been used for the regular size aleph as surplus. The midrash concludes that the Almighty Himself, as it were, took that extra ink and lovingly placed it on Moshe’s forehead; that is what gave rise to Moshe “rays of splendor.”

This is why it says, “And He called to Moshe” the word Vayikra (and He called) being written with a small letter Alef. This is to imply that HaShem, who is the Aluf (commander) of the universe, is concealed within every Jewish soul, and calls out to it to return. These are the thoughts of teshuva that come to one. However, he does not understand that this is HaShem, blessed be He calling to him.

During Temple times, the reading of the Torah was completed, by every congregation, in three and a half years. Today most congregations complete the reading of the Torah on one year.

In Israel, during Temple days, the reading of the Torah was completed once in three and a half years (see Triennial Cycle) and therefore the Torah was divided into 154 (or, according to another version, 167) weekly portions called sedarim. In Babylonia, during Temple days, the full cycle of the reading of the Torah was completed in one year, so that the Torah was divided into 54 parashiyot, weekly portions and that division is followed today, in continuance of the Babylonian tradition.

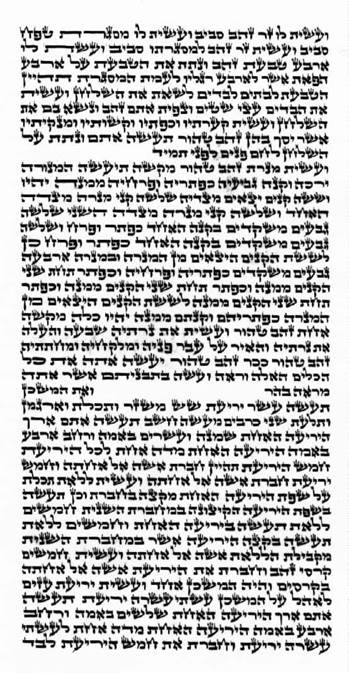

The division of the body of the text into sections is an ancient one, and unlike the above-mentioned division into sedarim and parashiyot, is connected with the very copying of the text whether in a scroll or a codex. These sections are of two kinds, with the type of space between them varying:

(1) A parasha petuhah (open parasha) which starts at the beginning of a line, the preceding line being left partly or wholly blank (in some printed editions this is indicated by p);

(2) A parashah setumah (closed parasha) which begins at a point other than the start of a line, whether the preceding parasha ended in the preceding line (at its end or not) or whether it ends in the same one, in which case a space of approximately nine letters is left between the two parashiyot (in some printed editions this is noted as s).

This ancient division is attested to in the Babylonian Talmud (Shab. 103b): “a parasha petuha should not be made setumah, a setumah should not be made petuhah.” Sifra to Lev. 1:1; 1:9 asks: “And what purpose did the sections serve? To give Moshe an interval to reflect between parashah and parasha and between issue and issue.” Despite their antiquity different traditions developed even on the matter of the parashiyot, that is, different customs, as to the place and number of each type. In printed editions today there is a great degree of uniformity in the Torah due mainly to the legal fixing of this issue and that of the form of the songs by Maimonides following Ben-Asher (Yad, Sefer Torah 8:4).

* * *

Mem is the 13th letter of the alephbet. It appears in two forms. Anywhere in a word except at the end it is square shaped with an opening in the lower left corner and yod like appendage in the upper left corner - מ. At the end of a word it appears as a closed square shape with the same yod like appendage - ם called a mem sofit.

There is one exception in the Torah where the final mem (mem sofit) is used in the middle of a word. The word and verse are found in Isaiah 9:6. There it is written: “lemarbeh hamisrah, his rule will be increased”. The mem in lemarbeh is a final mem.

The world of Mashiach, when HaShem will “annihilate death forever” and “banish the spirit of impurity from the world” is represented by the letter “final mem,” whose form is that of a closed square ם (as alluded to in the verse, “For the increase of the realm and for peace without end” (Isaiah 9:6), in which the letter mem uncharacteristically appears in its closed form in the middle of a word). In this future world of divine perfection, the gap between spirit and matter will be closed and the negative “fourth side” will be transformed into a positive force

o - The closed, Final Mem, represents the era of Mashiach as explained in Kabbalah.

Yeshayahu (Isaiah) 9:6 For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace.

oukaku vranv[(vcrnk) vcrok u

u,fknn-kgu sus txf-kg .e-iht

vesmcu ypanc vsgxkušv,t ihfvk

,utcm vuvh ,tbe okug-sgu v,gn

:,tz-vag,

Sanhedrin 94a Of the increase[18] of his government and peace there shall be no end.[19] R. Tanchum said: Bar Kappara expounded in Sepphoris, Why is every mem in the middle of a word open, whilst this is closed?[20] — The Holy One, blessed be He, wished to appoint Hezekiah as the Messiah, and Sennacherib as Gog and Magog;[21] whereupon the Attribute of Justice[22] said before the Holy One, blessed be He: ‘Sovereign of the Universe! If Thou didst not make David the Messiah, who uttered so many hymns and psalms before Thee, wilt Thou appoint Hezekiah as such, who did not hymn Thee in spite of all these miracles which Thou wroughtest for him?’ Therefore it [sc. the mem] was closed.[23] Straightway the earth exclaimed: ‘Sovereign of the Universe! Let me utter song before Thee instead of this righteous man [Hezekiah], and make him the Messiah.’ So it broke into song before Him, as it is written, From the uttermost part of the earth have we heard songs, even glory to the righteous.[24] Then the Prince of the Universe[25] said to Him: ‘Sovereign of the Universe! It [the earth] hath fulfilled Thy desire [for songs of praise] on behalf of this righteous man.’[26] But a heavenly Voice cried out, ‘It is my secret, it is my secret.’[27] To which the prophet rejoined, ‘Woe is me, woe is me:[28] how long [must we wait]?’ The heavenly Voice [again] cried out, ‘The treacherous dealers have dealt treacherously; yea, the treacherous dealers have dealt very treacherously:[29] which Raba — others say, R. Isaac — interpreted: until there come spoilers, and spoilers of the spoilers.[30]

* * *

We find that the intention of having a letter in the Torah appearing diminished is to also interpret the word without that letter, such as Bereshit 23:2, where the word “v’liv*k*osoh” appears with a small Kof and is interpreted as “u’l’vitoh,” - and for her daughter (See Rashi ad loc).

* * *

“In the beginning of Divrei HaYamim [the Book of Chronicles] Adam HaRishon’s name is written with a large Alef, because Adam considered himself to be very important. After all, none other than HaShem Himself had created him! Adam HaRishon was aware of his own significance, which later led to the sin of the Eitz HaDaat [Tree of Knowledge].

* * *

The

inverted “nun” (![]() ) in nine passages (Num. x. 35, 36; Ps. cvii. 23-28, 40).

) in nine passages (Num. x. 35, 36; Ps. cvii. 23-28, 40).

The Book of Numbers is like the voyage of the S. S. Titanic: it begins with the people in a festive mood, neatly arranged by camps around their sacred center, the Sanctuary; there are a few darker hints, but these are so subtle as to go almost unnoticed. The travelers expect a calm and pleasant journey, and to arrive at their destination quickly; suddenly, in mid-voyage they strike an iceberg and everything changes. In the Torah, this iceberg takes the concrete form of a pair of inverted Hebrew letters, the “nun”s framing Num 10:35-36, after which everything starts to go wrong. The ship may not sink, but an entire generation will die in the desert and fail to complete their journey; here, the catastrophes are not natural, but man-made: a collective failure of character In a very real sense, everything must start anew after these events.

* * *

There

are about 100 abnormal letters in the Masoretic text of the Bible—many of them

in the Pentateuch—which were always copied by the scribes, and appear also in

the printed editions. Among these

letters are: the ו; bisected vav, in the word ouka (“peace”;

Num. xxv. 12); the final “mem” in the word vcrok (“increase”; Isa. ix. 6 [A. V. 7]); the inverted

“nun” (![]() ) in nine passages (Num. x.

35, 36; Ps. cvii. 23-28, 40); and the Suspended Letters.

The principal division of these abnormal

letters is into small (“ze’ira”) and large

(“rabbati”) letters, as

indicated in the lists which are given below. The former appear to belong to an

older Masorah than that which provides for the large letters,

and should be classed with the “kere” and “ketib.”

) in nine passages (Num. x.

35, 36; Ps. cvii. 23-28, 40); and the Suspended Letters.

The principal division of these abnormal

letters is into small (“ze’ira”) and large

(“rabbati”) letters, as

indicated in the lists which are given below. The former appear to belong to an

older Masorah than that which provides for the large letters,

and should be classed with the “kere” and “ketib.”

References in Talmud and Midrash.

The references in Talmud and Midrash which are probably the bases of these abnormalities are as follows: (1) Citing “For in Y H the Lord created the worlds” (Isa. xxvi. 4, Hebr.), R. Judah b. Ila’i said: “By the letters ‘yod’ [Y] and ‘he’ [H] this world and the world to come were created—the former by the ‘he,’ as it is written otrcvc [“when they were created,” Gen. ii. 4]” (Men. 29b); hence the letter “he” is small here, indicating this world. (2) Citing “And when she saw him that he was a goodly child” (cuy; Ex. ii. 2), R. Meïr said: “‘Ṭob’ [“good”] was his name” (Ex. R. i.; Yalḳ., Ex. 166). (3) “And the Lord called unto Moshe” (trehu; Lev. i. 1); “va-yikra” is written here with a small “alef,” to emphasize its contrast with “va-yikar” in the verse “God met Balaam” (rehu; Num. xxiii. 4); the former indicates a familiar call used by loved ones, but the latter refers to an accidental meeting, difference being thus expressed between the call of HaShem to a Jewish prophet ( Moshe) and His call to a non-Jewish prophet (Balaam; Lev. R. i.). (4) “And Caleb stilled the people” (xvhu; Num. xiii. 30). He used diplomacy in quieting them, as he feared they might not heed his advice (see Sotah 35a; Yalk., Num. 743); and the use of the large טsymbolically denotes the way in which Caleb quieted the people. (5) “Hear, O Israel . . . one God” (Deut. vi. 4). Whosoever prolongs the word “echad” [one] in reciting the “Shema’” prayer, his days and years shall be prolonged—especially if he prolongs the letter “dalet” (Ber. 13b). The emphasis on the “dalet” (ד) is intended to distinguish it from the “resh” (ר), which resembles it, and which would change the reading to “acher” (another)—in this case a blasphemous expression. Proverbs (hkan) begins with a large “mem”—which has the numerical value of forty—because Solomon, like Moshe, fasted forty days before penetrating to the secret of the Torah. According to another explanation, the “mem” is the center of the alphabet, as the heart is the center of the body, the fountain of all wisdom, as revealed in Solomon’s Proverbs (Yalk., Prov. 929). The large “vav” in “Vayezatha” (t,zhu; Esth.ix. 9) is accounted for by the fact that all of Haman’s ten children were hanged on one large cross resembling the “vav” (ו; Yalḳ., Prov. 1059). The “zayin” in the same name is small, probably to indicate that Vayezatha was the youngest son.

Other large letters were intended to guard against possible errors; for instance, in the passage “when the cattle were feeble” (;hygvcu; Gen. xxx. 42) final “pe” (;) is written large in order that it may not be mistaken for a final “nun” (ן) and the word be read ihygvcu (comp. uhbhng in Job xxi. 24). The Septuagint translation, based on the second version, is “whenever the cattle happened to bring forth.”

The large letters in the words “ha-ke-zonah” (Gen. xxxiv. 31), “ha-la-Yhwh” (Deut. xxxii. 6), and “ha-le-’olamim” (Ps. lxxvii. 8) are probably meant to divide the root from the two preformatives. Some books begin with large letters, e.g., Genesis, Proverbs, and Chronicles; perhaps originally these were divided into separate compilations, each beginning with a large letter. The large “mem” in “ma chobu” (Num. xxiv. 5) is probably meant to mark the beginning of the column as designated by the Masorah.

Jacob b. Asher, author of the “Churim,” gives in his annotations to the Torah various reasons—some of them far-fetched—for the small letters. He says, for instance: “The small ‘kaf’ of v,fcku, in the verse ‘Abraham came to mourn for Sarah and to weep for her,’ indicates that Abraham really cried but little, since Sarah died in a ripe old age. The small ‘kof’ [=100] in h,me, in the verse ‘Rebekah said to Isaac: I am weary of life’ [Gen. xxvii. 46], indicates the height of the Temple, 100 cubits. Rebekah in her prophetic vision saw that the Temple would be destroyed, and therefore she became weary of life.”

SUSPENDED LETTERS

There are four suspended or elevated (“teluyah”) letters in the Hebrew Bible: (1) the “nun” in vabn, in Judges xviii. 30; (2) the “‘ayin” in rghn, in Ps. lxxx. 13; (3) the “‘ayin” in ohgar, in Job xxxviii. 13; and (4) the “‘ayin” in ohgarn, ib. verse 15. This masorah is mentioned in the Talmud, and appears to be earlier than that of the small and large letters.

The object in suspending the letters in question is not quite clear. The Rabbis proposed to eliminate the suspended “nun” and to read “Moshe” in place of “Manasseh,” as Gershom was the son of Moshe (I Chron. xxiii. 15); it is only, they said, for the reason that Jonathan (the son of Gershom) adopted the wickedness of Manasseh that he is called “the grandson of Manasseh” (B. B. 109b; comp. Yer. Ber. ix. 3). But the difficulty is that there is no record that Moshe’s son Gershom had a son named Jonathan, his only known son being Shebuel (I Chron. xxvi. 24). On the other hand, Jonathan, the priest of the Danites, was evidently a young Levite (Judges xviii. 3), and not the son of Manasseh.

Commenting on the suspended “‘ayin” in the word rghn, the Midrash says that the word may also read (without the “‘ayin”) ruhn=ruthn= “from the river or the sea.” The boar or swine coming from the sea is less (another version “more”) dangerous than that from the forest (Lev. R. xiii.). This refers to the Roman government, which is compared to the swine (Gen. R. lxviii.; see also Krochmal, “Moreh Nebuke ha-Zeman,” xiii.).

Regarding the suspended “‘ayin” in the word ohgar, occurring twice in Job, the Talmud eliminates the letter and reads ohar, which word has a double meaning—”rulers” and “poor”—the tyrants below who are poor and powerless above. But, it is explained, out of respect to King David the rulers in this case were not identified with the wicked; hence the spelling ohgar (Sanh. 23b; see Rashi ad loc., and Geiger, “Urschrift,” p. 258).

A more plausible explanation is that the suspended letters are similar in origin to the “kere” and “ketib.” In this case the authorities, who could not decide between two readings, whether the letter in question preceded or followed the next letter, placed it above, so that it might be read either way. Thus the original reading in Judges was probably “Jonathan, the son of Gershom in Manasseh” = vabhfc (comp. Judges vi. 15), i.e., in the land of Manasseh, whither the Danites emigrated. Another reading was “the son of Moshe” (van ic); and the suspended “nun” makes it possible to read the word either way (“ Moshe” or “Manasseh”). Another possible explanation is that the original reading was “Mosheh,” the “nun” being introduced to suggest “Manasseh,” so as to avoid the scandal of having a grandson of Moshe figure as the priest of an idolatrous shrine. The suspended “‘ayin” of rghn makes the second reading rhgn, “of the city,” referring to the capital Rome as alluded to in the Midrash. The word ohgar in Job, if the “shin” and “‘ayin” be transposed, reads ohagr, “storms” (the plural of agr); this change brings the verses into entire harmony with the context and in accord with the previous chapter (comp. Job xxxvii. 3, 4, 6, 11 with ib. xxxviii. 1, 9, 22, 28, 34, 35).

TAGIM - CROWNS

Decorative

“crowns” which are sometimes placed on the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. The taga is regularly composed of three flourishes or strokes, each of which resembles a

small “zayin” and is called “ziyyun” (![]() = “armor,” i.e., “dagger”). In the Nazarean

Codicil the taga is called “tittle” (Matt. v. 18). The seven letters צ, ג, ו, נ, ט ע, ש have the

crowns on the points of the upper horizontal bars. The flourishes are placed on

the tops of the letters, and they are found only in the Scroll of the Law, not in the printed copies of the Torah. The tagin are a part of the Masorah. According to tradition, there existed a manual, known as “Sefer ha-Tagin,” of the tagin as they appeared on

the twelve stones that Joshua set up in the Jordan, and later erected in Gilgal (Josh. iv. 9, 20). On

these stones were inscribed the books of Moshe, with the tagin in the required

letters (Nachmanides on Deut. xxvii. 8). The baraita of “Sefer ha-Tagin” thus

relates its history: “It was found by the high priest Eli, who delivered it to the prophet Samuel, from

whom it passed to Palti the son of Laish, to Ahithophel, to the prophet Ahijah

the Shilonite, to Elijah, to Elisha, to Jehoiada the priest, and to the Prophets, who buried it under the

threshold of the Temple. It was removed

to Babylon in the time of King Jehoiachin by the prophet Ezekiel. Ezra brought it back to Jerusalem in the time of Cyrus. Then it came into the possession of Menahem, and from him

was handed down to R. Nechunya ben ha-Hanah, through whom it went to R. Eleazar

ben ‘Arak, R. Joshua, R. Akiba, R. Judah, R. Miyasha (

= “armor,” i.e., “dagger”). In the Nazarean

Codicil the taga is called “tittle” (Matt. v. 18). The seven letters צ, ג, ו, נ, ט ע, ש have the

crowns on the points of the upper horizontal bars. The flourishes are placed on

the tops of the letters, and they are found only in the Scroll of the Law, not in the printed copies of the Torah. The tagin are a part of the Masorah. According to tradition, there existed a manual, known as “Sefer ha-Tagin,” of the tagin as they appeared on

the twelve stones that Joshua set up in the Jordan, and later erected in Gilgal (Josh. iv. 9, 20). On

these stones were inscribed the books of Moshe, with the tagin in the required

letters (Nachmanides on Deut. xxvii. 8). The baraita of “Sefer ha-Tagin” thus

relates its history: “It was found by the high priest Eli, who delivered it to the prophet Samuel, from

whom it passed to Palti the son of Laish, to Ahithophel, to the prophet Ahijah

the Shilonite, to Elijah, to Elisha, to Jehoiada the priest, and to the Prophets, who buried it under the

threshold of the Temple. It was removed

to Babylon in the time of King Jehoiachin by the prophet Ezekiel. Ezra brought it back to Jerusalem in the time of Cyrus. Then it came into the possession of Menahem, and from him

was handed down to R. Nechunya ben ha-Hanah, through whom it went to R. Eleazar

ben ‘Arak, R. Joshua, R. Akiba, R. Judah, R. Miyasha (![]() ), R.

Nahum ha-Lablar, and Rab.”

), R.

Nahum ha-Lablar, and Rab.”

Referred to in the Talmud.

The Aramaic language and the Masoretic style of the “Sefer ha-Tagin” would fix the time of its author as the geonic period. But the frequent references in the Talmud to the tagin suggest the probability of the existence of “Sefer ha-Tagin” at a much earlier period. Raba said the seven letters צ, ג, ו, נ, y, g, ש must each have a taga of three daggers (Men. 29b). The letter ה likewise has a taga (ib.). The taga of the ד is also referred to (Sotah 20a). The taga of the “kof” is turned toward the “resh” (Shab. 104a; ‘Er. 13a). R. Akiba was wont to interpret every point with halakic references (‘Er. 21b). The Haggadah calls the tagin “ketarim.” “When Moshe ascended to heaven he found the Holy One ‘crowning’ the letters” (Shab. 89a). In the Midrash, in the comment on Hezekiah’s reception of the ambassadors of Merodach-baladan, to whom he showed the “precious things” (Isa. xxxix. 2), R. Johanan says, “He showed them a dagger swallowing a dagger”; and R. Levi adds, “With these we fight our battles and conquer” (Cant. R. iii. 3; comp. Sanh. 104a; Pirke R. El. lii., end). Nachmanides (1194-1270) quotes this midrash with the reading, “Hezekiah showed them the ‘Sefer ha-Tagin’” (comment on Gen. i. 1). Maimonides evidently quotes the formula of the tagin for the phylacteries and the mezuzah scrolls from the “Sefer ha-Tagin” (see “Yad,” Tefillin, ii. 9; Mezuzah, v. 3); in his responsa “Pe’er ha-Dor” (No. 68, p. 17b, ed. Amsterdam, 1765) he says, “The marking of the tagin in the Sefer Torah is not a later custom, for the tagin are mentioned by the Talmudists as ‘the crowns on the letters.’ . . . The Torah that Moshe wrote also contained tagin.”

The Vitry Machzor of R. Simchah (written in 1208), a disciple of Rashi, copied the “Sefer ha-Tagin” (pp. 674-683). Menahem b. Zerahiah (1365), in “Chedah la-Derek” (I. i., § 20), says, “The ‘Sefer ha-Tagin’ is veiled in mysticism.” Profiat Duran, in the introduction to “Ma’asch Efod” (ed. Friedländer, p. 12, Vienna, 1865), says of the “Sefer ha-Tagin,” “They were scrupulous in maintaining the form of the letters as revealed to Moshe, inasmuch as they feared that a change might affect the efficacy attached to them.” To R. Eleazar of Worms (1176-1238), the author of “Rokeach” and of several cabalistic works, also is asscribed a “Sefer ha-Tagin” (Neubauer, “Cat. Bodl. Hebr. MSS.” No. 1566), which was, perhaps, his commentary on the text of “Sefer ha-Tagin”; he was not the author of the original book, as Zunz erroneously thought (see Zunz, “Z. G.” p. 405, and note 2), since Nachmanides, who flourished about the same time as R. Eleazar of Worms, quotes the “Sefer ha-Tagin” from the Midrash.

Kabalistic Significance.

The significance of the tagin is veiled in the mysticism of the Kabbala. Every stroke or sign is a symbol revealing, in connection with the letters and words, the great secrets and mysteries of the universe. The letters with the tagin are supposed, when combined, to form the divine names by which heaven and earth were created, and which still furnish the key to the creative power and the revelation of future events. These combinations, like the Tetragrammaton, were sometimes misused by unscrupulous scholars, especially among the Essenes. Hence, perhaps, the injunction of Hillel: “He who makes a common use of the crown [taga] of the Torah shall waste away” (Ab. iv. 7); to which is added, “because one who uses the Shem ha-Meforash has no share in the world to come” (Ab. R. N. xii., end); the words of Hillel, however, may be interpreted figuratively (Meg. 28b).

A plausible explanation of the tagin is that they are scribal flourishes, “‘ibbur soferim” (decoration of the scribes), the intention being to ornament the scroll of the Law with a “keter Torah” (crown of the Law), for which purpose the letters ו, ג, ט, ע, ש, צ, ג were chosen because they are the only letters that have the necessary bars on top to receive the tagin, excepting the letter “vav,” of which the top is very narrow, and the “yod,” whose head is turned aside and has a point (“choch”) on the bottom. The tagin of the other letters were intended probably to serve as diacritical points for distinguishing between ב and ב, ח and ח, ך and ך, ו and ו, ם and מ wherever a mistake was possible. Technically, as noted above, a taga is composed of three ziyyunin, or daggers. A line or stroke placed on a letter with a flat top is called “keren” (= “horn”), but as a rule authors are not careful to descriminate between the terms “horn” and “dagger.”

List.

The “Sefer ha-Tagin” gives a list of the unusual occurrences of the tagin and other flourishes in the Torah, as follows (the tops of the letters being called “heads” and the shafts “legs”):

(1) alef, 7 letters each with 7 tagin;

(2) bet, 4 letters with 3;

(3) gimel, 3 letters with 4;

(4) dalet, 6 letters with 4, and 1 letter with 1;

(5) he, 360 letters with 4 horns disjoined (not penetrating inside);

(6) he, 18 letters with 1 horn and joined (penetrating inside);

(7) vav, 38 letters with raised heads and legs coiled forward;

(8) zayin, 14 letters with only one taga in the center;

(9) zayin, 9 letters without tagin, but with coiled heads;

(10) Chet, 28 letters with 3 horns, 2 backward and 1 forward;

(11) Chet, 37 letters with legs astride;

(12) Chet, 67 letters with 4;

(13) yod. 83 letters coiled like a “kaf”;

(14) kaf, 58 letters with 3;

(15) final kaf, 74 letters with 4 horns;

(16) final kaf, 3 letters with their legs coiled forward;

(17) lamed, 44 letters with long necks, and tagin lowered from the top beside the neck, forming something like a “yod” at the lower end;

(18) mem, 39 letters with 3;

(19) final mem, 130 letters with 3 tagin disjoined;

(20) nun, 50 letters with their hooks coiled backward;

(21) final nun, 16 letters with heads coiled, but without tagin;

(22) samek; 60 letters with 4 tagin disjoined;

(23) ‘ayin, 17 letters with hind heads suspended;

(24) ‘ayin, 8 letters with tails coiled backward;

(25) ‘ayin, 6 letters with heads coiled backward;

(26) pe, 83 letters with 3;

(27) pe, 191 letters without tagin, but with the mouth coiled inside;

(28) final pe, 11 letters with 3;

(29) final pe, 3 letters with mouth coiled inside;

(30) Tzade, 70 letters with 5;

(31) Tzade, 2 letters without tagin (all the rest have 3 tagin);

(32) final Tzade, 8 letters with 5;

(33) Kof, 181 letters with 3 tagin disjoined;

(34) Kof, 2 letters without tagin, but with legs coiled backward;

(35) resh, 150 letters with 2 horns;

(36) shin, 52 letters with 7 horns;

(37) taw, 22 letters with higher heads than are usual.

Variations.

There are some variations of this list in the Vitry Machzor, in the “Badde ha-Aron” of R. Shem-Ṭob (13th cent.), and in Ginsburg’s “Massoretico-Critical Text of the Hebrew Bible.” Maimonides (Responsa, No. 68) says, “The tagin vary in the number of daggers, some letters having one, two, three, or as many as seven. . . . Owing to the lapse of time and the exilic troubles there were so many variations in this Masorah that the authorities considered the advisability of excluding all tagin. But since the validity of the scroll does not depend on the tagin, the Rabbis did not disturb them.” This probably accounts for the fact that only the tagin on the letters צ, ג, ו, ג, ט, ע, ש have been retained; those on all the other letters have been omitted in the scrolls of the Law used during the last three or four centuries (see R. Judah Minz, Responsa, No. 15; Shulkan ‘Aruk, Orach Chayyim, 36, 3).

ISOLATED LETTERS

The isolated letters (Tvrzvnm TvyTva) are the nine signs which appear between verses—in the Torah before and after the section of Nrah Asnb yhyv (Num. 10:35–36), and seven in Psalms, chapter 107. (There are differences of opinion as to their exact place and number.) Rather than being referred to by the name TvyTva (letters), they are already called Tvynmys (signs) in a baraita (about the Torah—Shab. 115b: ARN 34, 4; about Psalms-RH 17b). Their form was not fixed in the ancient sources and the scribes were quite liberal in the manner in which they noted them. There is early evidence that these simaniyyot were nothing but simple dots. This is the impression given by Sifrei Numbers, ch. 84 (ed. Horovitz, p. 80), already in the name of R. Simeon (second century C.E.). As time passed, these signs assumed various shapes and changed names accordingly. In tractate Soferim (prior to the eighth century) 6: 1, it is called, according to the version of various manuscripts, rupha (“horn”)—perhaps the sign really resembled a shofar, “and it appears indeed in the section on travels ( gobc hvhu )”—or dvpyS (spit), which is reminiscent of the sign of the abeloj (=spit). In Dikdukei ha-Te’amim (ch. 2) the term Tvrzvnm TvyTva is found, and according to Dunash b. Labrat it is Myrznmh TvyTvah (Teshuvot al Menahem, ed. Filipowski, p. 6a). The term is neutral and does not indicate the shape of the sign, and according to the basic meaning its root indicates that it refers to letters which are separated from the consonantal text. In the manuscripts the sign developed the shape of a reversed nun. It is not known whether all of it was reversed (see Okhlah we-Okhlah, b179), or only its top or bottom, but there was much confusion about it in the commentaries (see Minhat Shai on Num. 10:35; Nahalat Yaakov on tractate Soferim 6:1). There were even those who wrote it into the text itself instead of regular nuns (see also Ginsburg, The Masorah, vol. 2, 259). Later the names of these signs too were interchanged with the name for the regular reversed nun (see below). Hence the otiyyot menuzzarot became Tvrzvnm NynBn (see Masorah Magna to Ps. 107:23), which was explained, following rvHa Brzn ,”they turned backward” (Isa. 1:4), to mean reversed nun (Minhat Shai on Ps. 107:23), though there is no linguistic support for this interpretation. If the opinion already expressed in ancient sources regarding the signs in the Torah is generally accepted, that is, that the purpose of these signs is to separate the section “when the ark set forward” as if it were a book itself, there is no similar consensus of opinion concerning the signs in Psalms.

Beha’alotcha

One of the parshiyot (it’s a S’TUMA) is separated from the parshiyot before and after it by more than blank space (as is usual) - namely, backwards NUNs. Consequently, this parsha is the most isolated of all parshiyot.

Bamidbar (Numbers) 10:35-36 And it came to pass, when the ark set forward, that Moshe said, Rise up, HaShem, and let thine enemies be scattered; and let them that hate thee flee before thee. And when it rested, he said, Return, HaShem, unto the many thousands of Israel.

וַעֲנַן יְהוָה עֲלֵיהֶם, יוֹמָם, בְּנָסְעָם, מִן-הַמַּחֲנֶה. {ס} ׆ {ס}

וַיְהִי בִּנְסֹעַ הָאָרֹן, וַיֹּאמֶר מֹשֶׁה: קוּמָה יְהוָה, וְיָפֻצוּ אֹיְבֶיךָ, וְיָנֻסוּ

מְשַׂנְאֶיךָ, מִפָּנֶיךָ.

וּבְנֻחֹה, יֹאמַר: שׁוּבָה יְהוָה, רִבְבוֹת אַלְפֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל. {ס} ׆ {פ}

Before and after these two psukim we find the letter “nun” written back to front. This is the only place in the Torah where such a phenomenon occurs, while in Tanach it appears in chapter 107 of Tehillim. What do these inverted “nuns” symbolize? Chazal teach us: “The Torah made signs for this passage, in front of it and after, to say that this is not its place. But why was it written here? In order to make an interruption between one trouble and another” (Rashi Bamidbar 10:35 citing the Gemara in Shabbat 116a). Preceding these psukim, is the section “They journeyed from the mountain of HaShem” (Bamidbar 10:33), while the subsequent pasuk relates: “The people took to seeking complaints” (Bamidbar 11:1). The rightful place of these psukim is in the section detailing the encampment of each tribe. An appropriate place would have been immediately following the pasuk describing the traveling of the Mishkan: “the Tent of Meeting, the camp of the Levites, shall journey in the middle of the camps” (Bamidbar 2:17).

‘When the Ark would journey...’ This is to say that it is not in it’s place. Not just this, but it is a remez for the other place. [Therefore] the Torah makes signs with the reversed [Heb. hafchios] ‘nun.’ As the Talmud says, ‘A bent over [Heb. kafifah] nun [means] forced [Heb. kofif] faith.’ This means when the Jewish people will have all good in this world and they will be in submission to the service of HaShem. However if they are forced due to their sufferings, that is the level of a reversed ‘nun.’ Then the ark and the Torah are hidden from Israel.

For this reason Moshe prayed, ‘Arise HaShem And let your foes be scattered and your enemies from before you.’ These are the enemies of the Jewish people. Then the Ark and the Torah are not hidden. The ‘nun’ is not reversed. Their service to HaShem is with joy. (p. 53 sefer Aish Kodesh teachings of Rebbe Kolonymus Kalman HY’D* of Piasatzna, the son of Rebbe Elimeilech of Grodzisk)

EXTRAORDINARY DOTS

There are dots over 15 words in the Bible and sometimes also under them, one dot over each letter or over some of the letters. The words are distributed as follows: ten places in the Torah (in the tenth place in the Torah, Deut. 29:28, the dots cover eleven letters of three words—all but the last letter— dA vnynblv vnl), four places in the Prophets, the dots being above in each case, and one word in the Hagiographa (a@l@v@l@; (Ps. 27: 13), where there are dots also beneath the word. There are different traditions on the details. (See the full list in the Masorah Magna for Numbers 3:39, and in Okhlah we-Okhlah (ed. S. Frensdorff, 1864, b96), with the additional bibliography there.) These dots are a very ancient tradition, the evidence concerning some of them going back to the second century C.E.; see, for example, R. Yose in the Mishna (Pes. 9:2) concerning the he with a dot, in the word hcHr (Num. 9:10). A comprehensive list of the location of these dots in the Torah is already found in Sifrei Numbers chap. 69 (ed. Horovitz p. 64–65), R. Simeon bar Yohai being mentioned there; and further evidence is to be found in the Talmud and in the Midrashim. (The references were noted in the Arukh ha-Shalem under “naqad.” and to these should be added Ber. 4a; Naz. 23a; Hot. 10b.) There have been various theories put forth concerning the origin and meaning of these dots (see L. Blau, Masoretische Untersuchungen (Strassburg, 1891), 6–40: Zur Einleitung in die Heilige Schrift (Budapest, 1894), 113–20; R. Butin, The Ten Nequdoth of the Torah (Baltimore, 1906, repr. New York, 1969)); however, they do not belong to the system of vocalization and they also appear in Torah scrolls which are fit for public recitation.

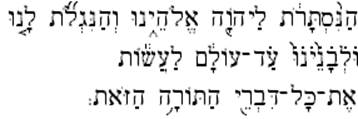

Devarim (Deuteronomy) 29:28 The secret [things belong] unto HaShem our God: but those [things which are] revealed [belong] unto us and to our children for ever, that [we] may do all the words of this law.

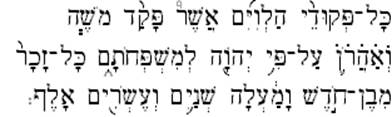

Bamidbar (Numbers) 3:39 All that were numbered of the Levites, which Moshe and Aaron numbered at the commandment of HaShem, throughout their families, all the males from a month old and upward, [were] twenty and two thousand.

* * *

Every One to Possess a Sefer Torah.

The Torah, written on a scroll of parchment. The Rabbis count among the mandatory precepts incumbent upon every Israelite the obligation to write a copy of the Torah for his personal use. The passage “Now therefore write ye this song for you, and teach it the children of Israel” (Deut. xxxi. 19) is interpreted as referring to the whole Torah, wherein “this song” is included (Sanh. 21b). The king was required to possess a second copy, to be kept near his throne and carried into battle (Deut. xvii. 18; Maimonides, “Yad,” Sefer Torah, vii. 1, 2). One who is unable to write the scroll himself should hire a scribe to write it for him; or if he purchases a scroll he should have it examined by a competent Sofer. If a Jew inherits a scroll it is his duty to write or have written another. This scroll he must not sell, even in dire distress, except for the purpose of paying his teacher’s fee or of defraying his own marriage expenses (Meg. 27a).

Method of Preparation.

The Torah for reading in public must be written on the skin (parchment) of a clean animal, beast or fowl (comp. Lev. xi. 2 et seq.), though not necessarily slaughtered according to the Jewish ritual; but the skin of a fish, even if clean, can not be used (Shab. 108a). The parchment must be prepared specially for use as a scroll, with gallnut and lime and other chemicals that help to render it durable (Meg. 19a). In olden times the rough hide was scraped on both sides, and thus a sort of parchment made which was known as “gewil.” Later the hide was split, the outer part, of superior quality, called “chelaf,” being mostly used for making scrolls of the Law, while the inner and inferior part, called “doksostos,” (= δύσχιστος), was not employed for this purpose. The writing was inscribed on the outer or hair side of the gewil, and on the inner or flesh side of the elaf (Shab. 79b). Every page was squared, and the lines were ruled with a stylus. Only the best black ink might be used, colored ink or gilding not being permitted (Massek, Soferim i. 1). The writing was executed by means of a stick or quill; and the text was in square Hebrew characters (ib.).

Size of the Scroll and Margin.

The

width of the scroll was about six

handbreadths (= 24 inches), the length equaling the circumference (B. B. 14a).

The Baraita says half of the length shall equal the width of the scroll when

rolled up (Soferim ii. 9). The length of the scroll in the Ark was six

handbreadths, equal to the height of the tablets (B. B. l.c.).

Maimonides gives the size of the regular scroll as 17 fingers (= inches) long (see below), seventeen being

considered a “good” number (![]() = 17).

Every line should be long enough to contain thirty letters or three words equal in space to that

occupied by the letters

= 17).

Every line should be long enough to contain thirty letters or three words equal in space to that

occupied by the letters ![]() . The lines are to be neither too short, as in an

epistle, nor too long, involving the shifting of the body when reading from beginning to end. The sheet (“yeri’ah”) must contain

no less than three and no more than

eight columns. A sheet of nine pages may be cut in two parts, of four and five columns respectively. The last column of the scroll may be narrower

and must end in the middle of the bottom line with the words ktrah kf hbhgk (Men. 30a).

. The lines are to be neither too short, as in an

epistle, nor too long, involving the shifting of the body when reading from beginning to end. The sheet (“yeri’ah”) must contain

no less than three and no more than

eight columns. A sheet of nine pages may be cut in two parts, of four and five columns respectively. The last column of the scroll may be narrower

and must end in the middle of the bottom line with the words ktrah kf hbhgk (Men. 30a).

The margin at the bottom of each page must be 4 fingerbreadths; at the top, 3 fingerbreadths; between the columns, 2 fingers’ space; an allowance being made of 1 fingerbreadth for sewing the sheets together. Maimonides gives the length of the page as 17 fingers, allowing 4 fingerbreadths for the bottom and 3 fingerbreadths for the top margin, and 10 fingerbreadths for the length of the written column. In the scroll that Maimonides had written for himself each page measured 4 fingers in width and contained 51 lines. The total number of columns was266, and the length of the whole scroll was 1,366 fingers (= 37.34 yds.). Maimonides calculates a finger-measure as equal to the width of 7 grains or the length of 2 (“Yad,” l.c. ix. 5, 9, 10), which is about 1 inch. The number of lines on a page might not be less than 48 nor more than 60 (ib. vii. 10). The Baraita, however, gives the numbers 42, 60, 72, and 98, based respectively on the 42 travels (Num. xxxiii. 3-48), 60 score thousand Israelites (Num. xi. 21), 72 elders (ib. verse 25), and 98 admonitions in Deuteronomy (xxviii. 16-68), because in each of these passages is mentioned “writing” (Soferim ii. 6). (At the present day the forty-two-lined column is the generally accepted style of the scroll, its length being about 24 inches.) The space between the lines should be equal to the size of the letters (B. B. 13a), which must be uniform, except in the case of certain special abnormalities the space between one of the Torahal books and the next should be four lines. Extra space must be left at the beginning and at the end of the scroll, where the rollers are fastened. Nothing may be written on the margin outside the ruled lines, except one or two letters required to finish a word containing more than twice as many letters.

Some scribes are careful to begin each column with initial letters forming together the words una vhc (“by his name YAH”; Ps. lxviii. 4), as follows: ,hatrc (Gen. i. 1), vsuvh (ib. xlix. 8), ohtcv (Ex. xiv. 28), rna (ib. xxxiv. 11), vn (Num. xxiv. 5), vshgtu (Deut. xxxi. 28). Other scribes begin all columns except the first with the letter “vav”; such columns are called “vave ha-’ammudim” = “the vav columns”.

It is the scribe’s duty to prepare himself by silent meditation for performing the holy work of writing the Torah in the name of God. He is obliged to have before him a correct copy; he may not write even a single word from memory; and he must pronounce every word before writing it. Every letter must have space around it and must be so formed that an ordinary schoolboy can distinguish it from similar letters (Shulkan ‘Aruk, Orach Chayyim, 32, 36; see Taggin). The scroll may contain no vowels or accents; otherwise it is unfit for public reading.

Verses.

The scroll is not divided into verses; but it has two kinds of divisions into chapters (“parashiyyot”), distinguished respectively as “petuchah” (open) and “setumah” (closed), the former being a larger division than the latter (Men. 32a). Maimonides describes the spaces to be left between successive chapters as follows: “The text preceding the Petuchah ends in the middle of the line, leaving a space of nine letters at the end of the line, and the petuchah commences at the beginning of the second line. If a space of nine letters can not be left in the preceding line, the petuchah commences at the beginning of the third line, the intervening line being left blank. The text preceding the setumah or closed parashah ends in the middle of the line, a space of nine letters being left, and the setumah commencing at the end of the same line. If there is no such space on the same line, leave a small space at the beginning of the second line, making together a space equal to nine letters, and then commence the setumah. In other words, always commence the petuchah at the beginning of a line and the setumah in the middle of a line” (“Yad,” l.c. viii. 1, 2). Maimonides gives a list of all the petuchah and setumah parashiyyot as copied by him from an old manuscript in Egypt written by Ben Asher (ib. viii., end). Asheri explains the petuchah and setumah differently, almost reversing the method. The general practise is a compromise: the petuchah is preceded by a line between the end of which and the left margin a space of nine letters is left, and commences at the beginning of the followingline; the setumah is preceded by a line closing at the edge of the column and commences at the middle of the next line, an intervening space of nine letters being left (Shulchan ‘Aruch).

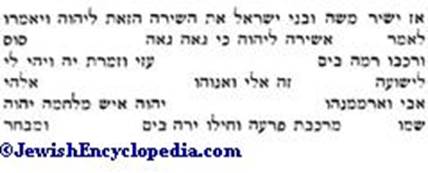

The poetic verses of the song of the Red Sea (“shirat ha-Yam”; Gen. xv. 1-18) are metrically arranged in thirty lines (Shab. 103b) like bricks in a wall, as illustrated below:

The first six lines are placed thus:

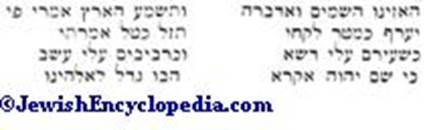

The verses of the song of “Ha’azinu” (Deut. xxxii. 1-43) are placed in seventy double rows, the first four lines as follows:

The scroll must be written in accordance with the Masoretic Ketib, the abnormalities of certain letters being reproduced (See Small and Large Letters). If the final letters l;.ioare written in the middle of a word, or if their equivalents fpmbn are written at the end, the scroll is unfit for public reading (Soferim ii. 10).

Name of God.

Scrupulous care must be taken in writing the Names of God: before every name the scribe must say, “I intend to write the Holy Name”; otherwise the scroll would be unfit (“pasul”) for public reading. When the scribe has begun to write the name of God he must not be interrupted until he has finished it. No part of the name may, extend into the margin outside the rule. If an error occurs in the name, it may not be erased like any other word, but the whole sheet must be replaced and the defective sheet put in the genizah. When the writing is set aside to dry it should be covered, with a cloth to protect it from dust. It is considered shameful to turn the writing downward (‘Er. 97a).

If an error is found in the scroll it must be corrected and reexamined by a competent person within thirty days; if three or four errors are found on one page the scroll must be placed in the genizah (Men. 29b).

The sheets are sewed together with threads made of dried tendons (“gidin”) of clean beasts. The sewing is begun on the blank side of the sheets; the extreme ends at top and bottom are left open to allow stretching. The rollers are fastened to the ends of the scroll, a space of two fingerbreadths being left between them and the writing. Every sheet must be sewed to the next; even one loose sheet makes the scroll unfit. At least three stitches must remain intact to hold two sheets together (Meg. 19a; Git. 60a).

Sewing the Sheets Together.

If the scroll is torn to a depth of two lines, it may be sewed together with dried tendons or fine silk, or a patch may be pasted on the back; if the tear extends to three lines, the sheet must be replaced. If the margin or space between the lines is torn, it may be sewed together or otherwise repaired. Care must be taken that every letter is in its proper place and that the needle does not pierce the letters.

A scroll written by a non-Jew must be put aside in the genizah; one written by a heretic (“apikoros”) or sectarian Jew (“min”) must be burned, as it is to be apprehended that he has wilfully changed the text (Gittim. 45b).

Every one who passes a scroll must kiss its mantle. The scroll may not be kept in a bedroom (M. 25a). A scroll of the Law may lie on the top of another, but not under the scroll of the Prophets, which latter is considered inferior in holiness to the scroll of the Torah (Meg. 27a).

Decayed and worn-out scrolls are placed in the Genizah or in an earthen vessel in the coffin of a talmid-Hakam (Ber. 26b).

Appurtenances.

The reverence with which the scroll of the Law is regarded is shown by its costly accessories and ornaments, which include a beautiful Ark as a receptacle, with a handsomely embroidered “paroket” (curtain) over it. The scroll itself is girded with a strip of silk and robed in a Mantle of the Law, and is laid on a “mappah,” or desk-cover, when placed on the almemar for reading. The two rollers, “etz hayyim,” are of hard wood, with flat, round tops and bottoms to support and protect the edges of the parchment when rolled up. The projecting handles of the rollers on both sides, especially the upper ones, are usually of ivory. The gold and silver ornaments belonging to the scroll are known as “kele chodesh” (sacred vessels), and somewhat resemble the ornaments of the high priest. The principal ornament is the Crown of the Law, which is made to fit over the upper ends of the rollers when the scroll is closed. Some scrolls have two crowns, one for each upper end.

The Breastplate.

Suspended by a chain from the top of the rollers is the breastplate, to which, as in the case of the crowns, little bells are attached. Lions, eagles, flags, and the Magen Dawid either chased or embossed, or painted, are the principal decorations. The borders and two pillars of Boaz and Jachin on the sides of the breastplate are in open-work. In the center there is often a miniature Ark, the doors being in the form of the two tablets of the Law, with the commandments inscribed thereon. The lower part of the breastplate has a place for the insertion of a small plate, bearingthe dates of the Sabbaths and holy days on which the scroll it distinguishes is used. Over the breastplate is suspended, by a chain from the head of the rollers, the Yad. In former times the crown was placed upon the head of the “Chatan Torah” when he concluded the reading of the Torah on the day of the Rejoicing of the Law, but it was not permitted to be so used in the case of an ordinary nuptial ceremony (Shulchan ‘Aruk, Orach hayyim, 154, 10). The people used to donate, or loan, the silver ornaments used for the scroll on holy days (ib. 153, 18). When not in use these ornaments were hung up on the pillars inside the synagogue (David ibn Abi Zimra, Responsa, No. 174, ed. Leghorn, 1651). In modern times they are placed in a drawer or safe under the Ark when not in use.

For domestic use, or during travel, the scroll is kept in a separate case, which in the East is almost invariably of wood; when of small dimensions this is sometimes made of the precious metals and decorated with jewels.

Personal Copies of the Torah.

The history of the dissemination of the scrolls of the Law is one of vicissitudes. While they were few in number at the time of the Chronicler (II Chron. xvii. 7-9), their number increased enormously in the Talmudic period as a result of a literal interpretation of the command that each Jew should write a Torah for himself, and also in consequence of the custom of always carrying a copy (magic influence being attributed thereto) on the person. In the later Middle Ages, on the contrary, the scrolls decreased in number, especially in Christian Europe, on account of the persecutions and the impoverishment of the Jews, even though for 2,000 years the first duty incumbent on each community was the possession of at least one copy (Blau, l.c. p. 88). While the ancient Oriental communities possessed scrolls of the Prophets and of the Hagiographa in addition to the scroll of the Law, European synagogues have, since the Middle Ages, provided themselves only with Torah scrolls and, sometimes, with scrolls of Esther. Six or nine pigeonholes, in which the rolls are lying (not standing as in modern times), appear in certain illustrations of bookcases (comp. Blau, l.c. p. 180; also illustrations in “Mittheilungen,” iii.-iv., fol. 4), these scrolls evidently representing two or three entire Bibles, each consisting of three parts, the Torah, the Prophets, and the Hagiographa. Curiously enough, the interior of the Ark in the synagogue of Modena is likewise divided into six parts (comp. illustration in “Mittheilungen,” i. 14).

SPACES IN THE TORAH

“And it came to pass while Israel dwelt in the land that Reuven went and lay with Bilhah his father’s concubine and Israel heard of it.” (Genesis 35:22)

Rashi mitigates the circumstances, insisting, on the basis of the Talmudic interpretation, that Reuven merely placed his father’s bed in Leah’s tent when - after Rachel’s death, Jacob had placed his bed in Bilhah’s tent. (B.T. Shabbat 55b). Whatever the interpretation, and even if Reuven’s only desire was to save his mother yet another mark of humiliation, it is never a son’s place to determine the private life of his father!

The final phrase in the verse, ‘And Israel heard of it,’ is followed by a blank white space in the Torah scroll; the Vilna Gaon suggests that wherever there is such a white space, it indicates that the subject of the verse - Jacob - wept.

* * *

There is usually a space in the Torah scroll separating one parashah from the next. As is well known, however, no such space exists in-between VaYigash and VaYechi. Rashi quotes the Midrash’s explanation of this phenomenon: “Why is this parasha ‘closed’? ...Ya’akov wanted to reveal to his sons [the time of] the End [of Days], but it was ‘closed off’ from him.” That is, God prevented him from doing so.

* * *

PARASHAT TZAV 5762

G-d spoke to Moshe saying, “Speak to the Israelites saying, ‘You may not eat any cheilev (forbidden fat) from oxen, sheep, or goats… You may not eat any blood… whether from birds or from animals’” (7:22-23,26).

The section bringing these two commandments is placed in the Torah towards the end of the laws of the offerings at the Temple. They have been part of the Israelite way of life ever since. They raise many points of interest, among which are:

1. What special qualities do cheilev and blood have, for which the Torah gives them the status of forbidden foods?

2. Cheilev and blood were both burnt on the Altar during Tabernacle and later Temple times. Yet the Torah explicitly states that the prohibition of eating cheilev applies to oxen, sheep, and goats only. It does not include species of animal that are ineligible for Temple offerings, such as the deer. In contrast, the Torah expressly forbids the consumption of blood from all animals and birds. Why does the Torah make that distinction?